Why had Clara taken me downstairs? To end up walking in the snow with me? Or had she meant something else and I had upset her plans by pressing the L for lobby button before she’d had a chance to press her floor? Did I do this to show that her apartment hadn’t crossed my mind? Or was I just trying to make it difficult because it would have been so easy to say, Show me your place.

Or did I not want to be with anyone tonight? Want to be alone. Want to go home. Yet want to be loved. For the distance between you and me, and, while we’re at it, between me and me, is leagues and furlongs and light-years away.

I want love, not others. I want romance. I want glitter. I want magic in our lives. Because there is so little of it to go around.

I thought of others in my place, so many young men, eager and selfless in their love, like Inky, traveling all the way to or back from wherever to stand outside her home, throwing clumps of snow at her window at night till their lungs give out and they waste and die, and all that stays is a song and a frozen footprint.

As I stood there, I put my hand in my pocket. It was filled with tiny paper napkins. I must have been nervous throughout the evening and, without thinking, stuffing napkins in my pockets each time I put down my glass or finished eating something. I remembered the handkerchief she’d given me during my bout with pepper. What had I done with it?

In my pocket I also felt the folded oversized invitation card on which the address of the party was printed in spirited filigree. I vaguely recalled, while talking to Clara at the party, that I’d frequently encounter this card in my pocket and would absentmindedly twiddle its corners, experiencing a sudden burst of joy when I put two and two together, and, in the fog of distracted thoughts, remembered that if the card was still damp from the storm, this could only mean I’d just come in from the snow, that the party was still young, that we were hours away from parting, and that there’d be plenty of time for anything to happen. And yet, even if behind these bursts of joy lingered something like light resentment for being dragged to this party, only to be stood up by my father’s friend, still, it may not have been resentment at all but yet another cunning way of allowing my thoughts to stray from where they wished to linger, only to be pulled right back to Clara and to the uncanny suspicion that Pooh might even have orchestrated a bit of what had happened tonight. Father died. I promised to look out for him. Lonely. Doesn’t know what to do with himself. Meet people.

I began to make my way toward Straus Park on the corner of West End and 106th Street. I wanted to think of her, think of her hand, of her shirt in the cold, that look when nasty humor twisted everything you mistook for harmless and straightforward and reminded you that I sing in the shower was drab, ordinary, flat-footed stuff. I wanted to think of Clara, and yet I was afraid to. I wanted to think of her obliquely, darkly, sparingly, as through the slits of a ski mask in a blizzard. I wanted to think of her provided I thought of her last, as someone I couldn’t quite focus on, someone I was beginning to forget.

And as I approached one of the lampposts to examine this feeling better and could almost see the lamppost lean its lighted head over my shoulder, as though, in exchange for helping me see things better, it sought comfort for trying so hard to give comfort, I began to think of the lamppost as a person who’d know what this twined feeling of near-bliss and despair was and explain it to me, seeing it had known me for years and surely would understand who I was or why I’d behaved the way I had tonight. It might tell me, if I asked, why life had thrown a Clara my way and watched me thrash about like someone reaching for a buoy that kept sinking. So you know, I wanted to say, you do understand? Oh, I do know and I do understand. And what do we do now? I asked. Do now? You travel all the way to a party and then can’t wait to leave when you’re dying to stay. What do you want me to say? You want guidance? An answer? An apology? There aren’t any. Distemper lacing its voice. The only other person I would speak with, and he is dead.

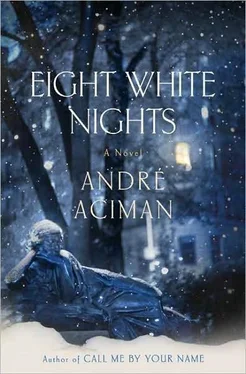

On the spot where West End Avenue converges with Broadway, I realized there’d be no way to find a cab here either, and as for the downtown M104, chances were no better than with the M 5 on Riverside. Thick, luminous, untouched snow lay everywhere. Not a car in sight, while the borders between sidewalks and streets, or between the streets and the park, or between the park and this invisible moment where Broadway and the northernmost tip of West End Avenue converge, all had disappeared. The snow mantled the entire area and made the city look like a boundless frozen lake from which protruded trees and strange undulations, the buried hoods of cars parked around Straus Park.

Inside the park, frozen, speckling boughs reached out heavenward, a cluttered show of stripped, gnarled, outstretched, earnest hands beckoning from Van Gogh’s olive groves like the tortured shtetlers of Calais huddling in the cold, while the intense white pool reflected at the base of each lamppost made everything seem unsullied, wholesome, and ceremonial, as though the streetlamps had filed up one by one to clear a landing spot for the lost Magi who alight on Christmas Eve.

How serene and silent the snow— candid snow, I thought, thinking back to Pokorny’s reconstruction of the Indo-European root of the word: *kand —to shine, to kindle, to glow, to flare, from which we get incense and incandescent. There was more candor in snow than in me. Let me light a candle here and think of Clara and of that moment in church, ages ago, when we put in a dollar each and lit candles for God knows whom.

I undid her knot and rewrapped my scarf around my neck, crossing both ends of the scarf snugly under my coat, the way I’d always done it. It wasn’t cold. I began to wonder whether the snow would stick and hold out till tomorrow. It never did these days. Slowly, as I made my way through the park, I found a bench and came up with a crazy notion. I must sit here. With my glove, I brushed off the snow and finally sat down, extending both legs in front of me like someone taking the sun on an early afternoon after a hearty midday meal.

I liked it here, and I loved the way both avenues and their adjoining streets seemed to blend in this one spot and, by disappearing in the snow, suddenly revealed that the Upper West Side had undercover harmonies and undisclosed squares that spring on you like stalls in movable marketplaces, new squares that come out with the snow and vanish no sooner than it melts. I could spend the night here and hope the snow stayed all night and all day tomorrow, so that I could return tomorrow night as well and find it lingering still, sit here on this very bench again, as if I had found a ritual and a hub all my own, and wait for the luster of the moment to wash over me again, even if I knew that the luminous patina I was projecting on Straus Park was weather-induced, and alcohol-induced, and love- and sex-induced, an accident and nothing more perhaps, like sitting on this and not another bench, or finding so much beauty because I couldn’t find a cab, or ending up here instead of on Riverside, or biting into a peppercorn instead of crème fraîche, standing, not in the library, where I might have met Beryl first and lived through an entirely different, perhaps better evening, but behind a Christmas tree — suddenly all these incidentals were filled with clarity, radiance, and harmony, hence joy — joy, like snow, that I knew would never last, joy of small miracles when they touch our lives, joy like light on an altar. I knew I would revisit this spot tomorrow night.

Читать дальше