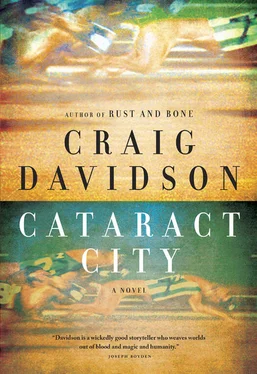

Dolly was elevated to B-Class for her second race soon after that — and the tote board listed her at 2–1 odds. She won. Then she won two more races in that class. And that’s when she was deemed ready for A-Class.

A few days later, Ed and I watched as Dolly smoked her A-Class debut over Silent Cruise, who had been tabbed as a world-beater. Afterwards an old gaffer sauntered up to me and in a deep Irish brogue asked, “Is that great galloping bitch for sale?”

He had associations back in Tipperary, he claimed, and was an informal scout for punters at the famous Thules dog track. “She may not always win,” he said of Dolly, “but Lo’, she puts on a rollicking show. The yobbos back home would love ’er.”

He hadn’t been surprised to hear Dolly wasn’t for sale.

“You’re smart to hold on to a bitch like thaa. A gold mine on four legs!”

How much longer would I let her race? The way she ran made it a huge risk every time the traps sprung. I couldn’t live with myself if she got hurt. I’d have stopped if not for the fact that Dolly seemed happiest in full flight.

By the time we got home that evening, the heat had set in. There were rolling blackouts across the city and our A/C was on the fritz. Edwina was edgy. We lay on the sofa reading by the light of tea candles. Her legs thrummed across my thighs. She screwed a knuckle into my ribs and play-slapped me.

“What’s up with you tonight?”

“Just feeling silly.”

The sticky warmth lay thick inside the walls. We had been sweating just to breathe. She stood up, pulling me into the bedroom. It may simply have been a way to break the heat inside of her, the same way a good thunderstorm will break a heat wave. She undressed in the moonlight falling through the window. Her body seemed carved out of that moonlight — a part of it, and distant in the same way. Before Ed, I’d had no experience with women. Sure, I’d kissed Becky Longpre on the Lions Club baseball bleachers, got my hand up her shirt before she protested about being a good Baptist girl, but that was it. My breath always quickened with Ed. My heart beat so fast I felt it over every inch of my body.

It was always a struggle to control myself, but Ed sensed that. She’d brace her hands on my shoulders and ease the shakes out of me, eyes telling me to take it slow. I only had to listen to her and obey.

I wondered what she was thinking in those moments. Part of her, maybe the deepest part, was locked off — even then, when we were that close. I figured a woman can’t be understood the way a man can. Women have purposes men can’t even imagine.

And then I felt that sweetness coming up from the balls of my feet. It wasn’t just the physical part; it was the body-closeness I would come to crave. But it’s never enough, is it? Two people can’t share the same heart, can they?

Afterwards she let out a jittery breath. “That was nice. You always try real hard, Dunk. A girl appreciates that.”

A girl appreciates that . It was as if she was giving me advice for down the line, when I’d find myself in bed with someone else.

Early the next morning I’d awoken for no reason I could name. Dolly’s head was perched on the edge of the bed, inches from my face. The weight of her skull spread her dewlap across the mattress. Had I been talking in my sleep? Had I called out to Dolly?

She snuffled softly and licked my cheek. Her tongue smelled of shaved iron. It wasn’t her style; Dolly was a standoffish creature.

Maybe something about the stillness of night had rewired the circuits in her brain, drawing her to me? I lay motionless, not wanting to break the spell.

Three weeks after Dolly’s A-Class win, a murmur passed through the Winning Ticket as Ed and I entered. The punters had pegged me as the owner of the mutt with the million-dollar legs. Ed slapped me on the shoulder and whispered in my ear: “You’re basking in the reflected glory of a dog. Drink it up, big shot.”

A weedy fellow in boater shoes and a brushed velvet coat wormed out of the crowd.

“The number four bitch in tonight’s final heat — yours, yeah? Is she well?” he asked. “Not got the shits, I hope? Should I put a ten-spot on her to be first on the bunny, first over the line?”

Other dogmen pressed in, twisting their racing forms in white-knuckled fists, waiting for my reply.

“She’s not shitting any differently than usual, if that helps.”

They peeled away like buzzards from a clean-picked carcass, grumbling as they drifted over to the betting wickets.

Harry waited for us in the kennels with Dolly. “This is the big time,” he said. “Open Class welcomes dogs from all over. The purse is decent enough that you’ll get dogmen coming up from New York and as far east as Maine. Your girl better not make her customary late dash — these dogs’ll be too quick for that.”

“Do you know any of the other dogs?” Edwina asked.

“Not so much the dogs as owners. Teddy Simms from Cheektowaga’s got one in trap two, a bitch named Hurricane Jessie. Simms works with some fast bloodlines. Lemuel Drinkwater’s here, too. He breeds over at the Tuscarora Nation outside Buffalo. A real bottom-liner, is Lemmy — loves a winner, no use for a loser. A couple years back he got DQ’d for the season. The vet was giving one of his winners the usual post-race once-over and wouldn’t you know it if a jalapeño pepper didn’t slide out of the poor dog’s ass.”

Harry took in our shocked expressions.

“Old dogman’s dirty trick. Slit a hot pepper with a razor blade, get those juices leaking out, stick it up your dog’s fanny. You better believe it’ll get him hopping.”

“Why is he still allowed to race?” I said.

“You take a look around this place? Not exactly a hive of morality, son.”

We sat in the stands for the prelims. The spotlights beat down on the red dirt of the track. Midges and no-see-ums rose from under the risers, dancing in the gathering dark. The tote board chittered as the odds rose and fell.

Railbirds clustered along the finishing stretch with tickets clutched in their sweaty fists, pounding the spectators’ rail as the dogs thundered down the final leg of each race. Afterwards the winners crowed—“I knew that boy was a mucker!” or “What a stayer, just like I told you!”—as the losers tossed their stubs on the blacktop alongside cigarette butts and crumpled beer cans.

Before Dolly’s heat I went down to the lockout kennel where the dogs were housed before each race. Harry stood with a tall man in his early thirties. The man wore pegged blue jeans and a jean jacket, his red-brown face shadowed by the brim of an Australian out-backer hat; fake crocodile teeth were strung around the brim like bullets in a bandolier. He reminded me of Billy Jack, the star of those seventies action flicks, except he didn’t have that actor’s face.

“Duncan,” Harry said, “meet Lemuel Drinkwater.”

We shook. Drinkwater’s hand was dry and chilly; it was like gripping cold muscle. He smiled but there was no kindness in it, no heat or nastiness either: he had a perfectly blank expression, reflecting nothing.

“We were jawing about your dog.” Drinkwater pronounced it darg . “How’d you train her to run that way, wide all the time?”

“I didn’t do anything. Just how she runs.”

He nodded the way a man does when he doesn’t believe you. But some men figure everyone’s lying to them all the time.

“She’s a quick dog,” Harry said. “Whoever chucked her in the garbage as a pup must be kicking themselves.”

Drinkwater shrugged. “Garbage is the best place for some of them.”

Harry pursed his lips like he wanted to say something but wouldn’t.

“Guess I got lucky, then,” I said.

Читать дальше