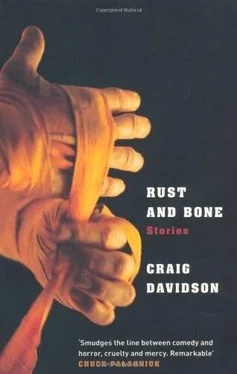

Rust and Bone

Stories by

Craig Davidson

More Praise for Rust and Bone

“Like a gleeful bull in the china shop of staid and worthy CanLit, Davidson is defining his own literary identity by shattering conventions.”

—

National Post

“[ Rust and Bone ] is a superb collection from a young writer who already feels fully formed. The stories give off an air of confidence, the kind of confidence one expects in the works of veterans like Alice Munro or William Trevor, as if Davidson is fully aware of what he can do and knows how to achieve his ends.”

—

Edmonton Journal

“ Rust and Bone gives Canadian fiction a healthy body shot.”

—

Calgary Herald

“Davidson … is a fine young writer with a keen sense of the absurd and a bracing, biting wit.”

—

Publishers Weekly

“Davidson matches his stellar, energetic descriptions of physical confrontation with subtle, quirky explorations of human motivation.”

—

Booklist

“Stark oppositions often pack the punch in these gritty tales about American tough guys on the ropes.… This salty collection more than whets the appetite.”

—

The Guardian

“Davidson’s debut collection engages the Hemingway-esque tradition of terse prose describing toughened men who suffer while hiding their scars.”

—

Kirkus Reviews

“Davidson’s forceful debut collection arrives like a jab to the jaw.… He is as adept at the humorous interplay of personality in a sex addicts anonymous meeting as he is in describing a vicious dogfight. There are also quiet moments of grace. Even when Davidson pushes the limits of what a reader can stomach, he never loses our attention or our empathy. Recommended as a young writer to watch.”

—

Library Journal

“Confident.… Impressive.… Rust and Bone might be described as ‘promising’ were it not already such a finished piece of work.”

—

The Times Literary Supplement

“Craig Davidson is a young author who already displays the surefootedness of a seasoned pro … these tightly balled, arrestingly visceral explorations of machismo’s dark recesses uncoil with concussive power.”

—

The Sunday Times

“This collection of stories by Canadian Craig Davidson sears the senses on contact.… Davidson has whittled his prose down to bare expression, eschewing pronouns and articles for a clean, spare feel, suited to the calculated violence of the stories … he manages to deal with substantial issues such as infertility, loss, and addiction in a way that indicates a latent sensitivity underlying the sheen of brutality.”

—

The Bloomsbury Review

TWENTY-SEVEN BONES make up the human hand. Lunate and capitate and navicular, scaphoid and triquetrum, the tiny horn-shaped pisiforms of the outer wrist. Though differing in shape and density each is smoothly aligned and flush-fitted, lashed by a meshwork of ligatures running under the skin. All vertebrates share a similar set of bones, and all bones grow out of the same tissue: a bird’s wing, a whale’s dorsal fin, a gecko’s pad, your own hand. Some primates got more—gorilla’s got thirty-two, five in each thumb. Humans, twenty-seven.

Bust an arm or leg and the knitting bone’s sealed in a wrap of calcium so it’s stronger than before. Bust a bone in your hand and it never heals right. Fracture a tarsus and the hairline’s there to stay— looks like a crack in granite under the x-ray. Crush a metacarpal and that’s that: bone splinters not driven into soft tissue are eaten by enzymes; powder sifts to the bloodstream. Look at a prizefighter’s hands: knucks busted flat against the heavy bag or some pug’s face and skin split on crossing diagonals, a ridge of scarred X’s.

You’ll see men cry breaking their hand in a fight, leather-assed Mexies and Steeltown bruisers slumped on a corner stool with tears squirting out their eyes. It’s not quite the pain, though the anticipation of pain is there—mitts swelling inside red fourteen-ouncers and the electric grind of bone on bone, maybe it’s the eighth and you’re jabbing a busted lead right through the tenth to eke a decision. It’s the frustration makes them cry. Fighting’s all about minimizing weakness. Shoddy endurance? Roadwork. Sloppy footwork? Skip rope. Weak gut? A thousand stomach crunches daily. But fighters with bad hands can’t do a thing about it, aside from hiring a cornerman who knows a little about wrapping brittle bones. Same goes for fighters with sharp brows and weak skin who can’t help splitting wide at the slightest pawing. They’re crying because it’s a weakness there’s not a damn thing they can do for and it’ll commit them to the second tier, one step below the MGM Grand and Foxwoods, the showgirls and Bentleys.

Room’s the size of a gas chamber. Wooden chair, sink, small mirror hung on the pigmented concrete wall. Forty-watt bulb hangs on a dark cord, cold yellow light touching my clean-shaven skull and breaking in spears across the floor. Cobwebs suspended like silken parachutes in corners beyond the light. Old Pony duffel between my legs packed with wintergreen liniment and Vaseline, foul protector, mouthguard with cinnamon Dentyne embedded in the teeth prints. I’ve got my hand wraps laid out on my lap, winding grimy herringbone around the left thumb, wrist, the meat of my palm. Time was, I had strong hands— nutcrackers, Teddy Hutch called them. By now they’ve been broken so many times the bones are like crockery shards in a muslin bag. You get one hard shot before they shatter.

A man with a swollen face pokes his head through the door. He rolls a gnarled toscano cigarillo to the side of his mouth and says, “You ready? Best for you these yahoos don’t get any drunker.”

“Got a hot water bottle?” Roll my neck low, touch chin to chest. “Can’t get loose.”

“Where do you think you are, Caesars Palace? When you’re set, it’s down the hall and up a flight of stairs.”

I was born Eddie Brown, Jr., on July 19, 1966, in San Benito, a hardscrabble town ten miles north of the Tex-Mex border; “somewhere between nowhere and adiós, ” my mother said of her adopted hometown. My father, a Border Patrol agent, worked the international fenceline running from McAllen to Brownsville and up around the horn to the Padre Island chain off the coast. On a clear July day you’d see illegals sunning their lean bodies on the projecting headlands, soaking up heat like seals before embarking on a twilight crossing to the shores of Laguna Madre. He met his wife-to-be on a cool September evening when her raft—uneven lengths of peachwood lashed together with twine, a plastic milk jug skirt—butted the prow of his patrolling johnboat.

“It was cold, wind blowing off the Gulf,” my mother once told me. “ Mío Dios . The raft seem okay when I go, but then the twine is breaking and those jugs fill with water. Those waters swimming with tiger sharks plump as hens, so many entrangeros borricos to gobble up. I’m thinking I’m seeing these shapes,” her index finger described the sickle of a shark’s fin. “I’m thinking why I leave Cuidad Miguel—was that so terrible? But I wanted the land of opportunity.” An ironic gesture: shoulders shrugged, eyes rolled heavenwards. “I almost made it, Ed, yeah?”

My father’s eyes rose over a copy of the Daily Sentinel . “A few more hours and you’d’ve washed up somewhere, my dear.”

The details of that boat ride were never revealed, so I’ll never know whether love blossomed or a sober deal was struck. I can picture my mother wrapped in an emergency blanket, sitting beside my father as he worked the hand-throttle on an old Evinrude, the glow of a harvest moon touching the soft curve of her cheek. Maybe something stirred. But I can also picture a hushed negotiation as they lay anchored at the government dock, maiden’s hair slapping the pilings and jaundiced light spilling between the bars of the holding cell beyond. She was a classic Latin beauty: raven hair and polished umber skin, a birthmark on her left cheek resembling a bird in distant flight. Many border guards took Mexican wives; the paperwork wasn’t difficult to push through. My sister was born that year. Three years later, me.

Читать дальше