[169]

In the end the sun set and another calibration began (maybe the ninth of the month). Other things happened in other places. We could write that men were killed there and there people died, and there they were born — but these things are understood.

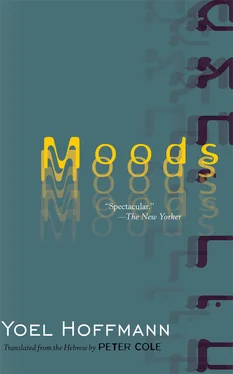

All this trouble of writing a book and printing a book and selling a book and reading a book and translating a book is a waste of time unless, in the end, it brings people joy.

And so, the past has already been. The future isn’t yet with us, and the present is only a future becoming a past. Joy? In what? Maybe in that the past has already been and the future is yet to come and the present can be either. Which is to say, that everything’s nothing.

There is no greater delight than that, since, if we look around us, the nothing is packed to the rafters.

[170]

As for war. They should call up reserves of literary critics. They’d vanquish the enemy with their weighty pronouncements. Afterward, the critics could enlist the lethal forces of verbal contortion and extensive annotation to verify that the enemy in fact had been crushed. Imagine the shock of (for instance) religious fanatics in the face of that technology.

There’s also a chance that, confronted with their sudden and frightening appearance on the battlefield, the enemy would simply experience a conversion and throw itself at their feet.

Which reminds us of Mrs. Unger, whom we once knew, when we lived in Haifa.

Usually Mrs. Unger was a very soft woman. She baked pecan cookies and poppy-seed cookies and read romance novels in Hebrew and in Hungarian.

But sometimes, maybe once every two months, she’d wave her right hand in the air (without moving the rest of her body) and slap her husband.

No wonder Mr. Unger always moved in such wide circles around his wife.

[171]

We miss poetry. Yesterday we read a poem in Ha’aretz about a swan that falls into the water and we too are trying to bring down a swan. But the swans get away and the sea is full of battleships.

Maybe one should begin artificially, without inspiration, and then inspiration will follow. Since now it’s night and everyone’s sleeping we could start with “The city breathes in chloroform.” Except that we’ve heard that chloroform hasn’t been used for ages in operating rooms, and we don’t know what sort of anesthesia they use today.

Maybe one needs to think about a single detail and not an entire city. Pertaining to Mr. Yellinek, for instance. On the face of it, there’s nothing poetic about Mr. Yellinek. But in fact, when he opens his mailbox day after day it’s impossible to look directly at him, just as one can’t stare at the sun (Mr. Yellinek is five feet three inches tall and barely reaches the mailbox) without going blind.

[172]

And there’s nothing more poetic than notes from the housing committee (each person owes such and such).

Or an antenna. But then you’re tempted to put birds on it and that ruins the poem. Generally. Whatever seems like a poem isn’t a poem and what doesn’t seem like a poem is.

Tiberias, for example, is full of poems. Also Afula. And Birmingham. Especially the hotel where we got a room for twenty pounds a night but had to climb over the beds to get to the shower.

We’ve already talked about phone books. Under “H” we find our name among others, and look at it (that is, at the name) and at the number beside it and don’t understand.

All these things (that is, not putting birds on the antenna and not understanding our name) are necessary conditions for poetry. But not sufficient. Something else is needed. Perhaps a great sadness or maybe great joy. Or quiet.

[173]

Maybe this quiet we long for is a sign that the book is nearing its end. We’re not sure.

Maybe from here on in we need to do what Joyce did in his final book and write in a kind of parallel language.

Something like O my mother in Hinfich feel phaned a slanguage a slanguage and more. Piraeus isn’t far. And the stubbledom oh the stubbledom. My mother whom our mother recovers the sea covers the great sees and more across unto pain extends to the end to the end. And if and mother and father and rivers and rivers oh no once again and again, oh since she has a very great ball and a dress made of others and a wonder and brother and canals of algae and cruel stubbling like a knife that our father that very same knife and a glinting or glash. O my mother the willow the bowl.

And so on. But there’s no escaping in that direction. Why not? This our readers understand quite well on their own.

[174]

After he’d written like that, Joyce wrote no more. When they asked him why, he answered roughly as follows: I’ll write only if I find very simple words, very very simple words.

We know some simple words. For example: “There once was a rabbit / who had the bad habit / of twitching the end of his nose. / His sisters and brothers / and various others / said, ‘Look at the way he goes!’”

Not a superfluous word. And one can see it all. The rabbit. The field he’s looking for food in. His sensitive nose. And it gets better:

“But one little bunny / said ‘Isn’t it funny’ / and practiced it down in the dell. / Said the others ‘If he can, / I’m certain that we can,’ / and they all did it rather well! // Now all the world over, / where rabbits eat clover / And dig and scratch with their toes, / Each little rabbit / has got the bad habit / of twitching the end of his nose!”

If only we could write like that.

Or the way that Louis Armstrong sang. Come to think of it, he too twitched his nose.

[175]

At some point along the way (maybe when we were infants even) something got scrambled and we started putting words on top of each other (and not side by side).

At school for sure. Louis Armstrong couldn’t read music. Why did they send us there? After all, we could already talk.

On the board the teacher wrote “Shalom, first grade,” but we cried. A woman came and said my name is Tzipporah and we wanted our mother. Why did they make us sit in chairs and tell us that we couldn’t move?

When we gave things names we did so as though in a dream. But then they forced us to give the names letters, and that was too much. They placed bright lights directly before us, as though the sun weren’t enough. Why did they make us sit in those chairs?

Then came the sin of addition. How much is such and such plus such and such? Before that we were never wrong. Only afterward did we start to make mistakes.

[176]

The first-grade chairs became computer chairs. Now we’re sitting in front of large screens, our face is pale and our spine is bent, and we send each other odd signs.

Sometimes the computers crash and entire love stories vanish. Addresses can’t be recovered and the faces aren’t yet known.

Stricken with sorrow, people head into the streets, carrying clumps of metal in their hands, but the technicians aren’t able to get the names and phone numbers out of them, and since the people have lost the power of speech, they withdraw into themselves, like that gray worm that shrivels up when you touch it.

Today the storks are coming to mothers giving birth. Each beak bears a small computer, and the whole world has been destroyed by a blackout.

[177]

Yesterday Mr. Yellinek asked Mr. Nahmias (the Liverpool fan) to lower his mailbox.

First, Mr. Nahmias removed the box from the wall. He leaned it against the stairwell wall and went to get a drill.

When he returned he asked Mr. Yellinek: Where do you want it? Mr. Yellinek made an arc-like motion with his hand (as though he were opening an imaginary mailbox) and said: Here.

Mr. Nahmias drilled a hole where Mr. Yellinek had indicated and, with light taps from his hammer, he inserted a plastic dowel into the hole. With the help of a screwdriver, into the dowel he turned a large screw, on which he hung the mailbox.

Читать дальше