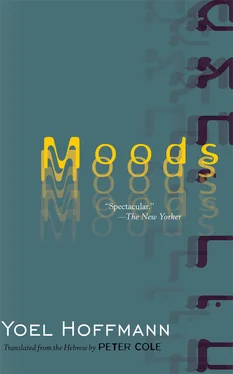

[1]

Ever since finishing my last book, I’ve been thinking of how to begin the next one.

Beginning is everything and needs to contain, like the seed of a tree, the work as a whole.

And so, what I see is the figure of a man descending (from the sidewalk?) five or six steps to a basement apartment, and he’s halfway there.

I know it’s a love story. And maybe there’s a woman in the basement apartment. It’s probably November.

[2]

I remember things that happened in an empty building (which is to say, one they hadn’t yet finished building) in Ramat Gan, in the fifties.

Then too (as now) legs were the principal thing. The world was full of legs of all sorts and there was movement in space. Someone — Ezra Danischevsky — said to me once: I want to be an elevator repairman (you can imagine the motion and its various directions).

In that (empty) building, a woman who’s now seventy-four (if she’s not dead) took off her dress.

[3]

And so his name — that of the man going down the steps — is, most likely, Nehemiah. Not because it’s true, but because of that combination of sounds—“his name” and “is. . Nehemiah,” and because of its implicit acknowledgment of God, without whom perhaps the world exists, though He is the master of words.

It’s hard to call a woman by name because Nothingness swallows everything, and the one contains the many, although, in other respects, highly partial, her name is possibly Hermione.

A policeman or two pass on the street and their legs are now on an imaginary plane above which sits the head of a man.

After my father died, I spritzed his deodorant into my armpits for three or four months. It smelled like musk.

My father also had a Schaffhausen watch, which wasn’t removed even when he fell into a coma.

[4]

I too (Yoel Hoffmann, that is) once went like that down steps to a place where a French woman waited.

I’d trailed her from the Metro stop to the building’s entrance, and since she looked at me and twirled the key on her finger suggestively, I followed her down to the basement apartment.

Maybe the scene with Nehemiah is only a memory of this scene, and what I did, he’ll do as well.

Bookstores hold an infinite number of memories like these, but only a few speak in praise of whores.

[5]

The act of love gives birth to blue birds, just as once we could walk through a door without having to open it. Girls set entire streets on fire. Kiosks floated into the air. People wailed as though in distress, but perfumed vapors rose from their lips.

In the room, the French woman held out a hand (one of the two she had) and took the thousand-franc bill, as one takes the wine and wafer from a priest.

[6]

A forty-watt bulb (elsewhere I’ve called it an electric pear) lit up the bed but the picture of the Virgin (and Child) stood outside the cone of light like an omen. Sometimes one sees a sign, like ARLOSOROFF STREET, and goes there, and in fact the street’s just like that.

The French woman pulled the dress up over her head and stood there utterly naked (I remember an accountant who always said, “Bottom line—” which is to say, “net”) — no bra, no panties.

[7]

Literature’s so pathetic. We peddle fabric with a sun painted on it and no one even looks up.

The bed. Thighs. The backside. A person who wants to know the flesh had best bite into his finger. Only then will he know.

And he should see my Aunt Edith. How she fell into herself, in the wheelchair, until her mouth sank into her jaw and her jaw sank into her chest and still she said — time after time, until she died— noch (which is to say, “more”).

[8]

The woman was maybe forty and had (she said) a child in the country. The act of love she undertook as one turns the pages of a newspaper ( Le Figaro , for example).

Undoubtedly. She thought of other things during intercourse. Maybe she saw a woman in the village calling her son: Claude, Claude. Or the candles that one lights at church. In any event, she held me, as the Virgin in the picture holds the Child, and sighed.

[9]

I could write about how the Bible that the principal gave me at the end of eighth grade saved my life (it was in the pocket of my army vest and the bullet went into it up to the Book of Nehemiah) or, how, as though in an American movie, I went to the wedding of a girl I was in love with once and at the last minute etcetera. Which is to say, a bona fide story with plot twists and intrigue and an ending cut off like a salami (to keep it modern).

Books like those have at least three hundred and twenty eight pages, and in the end mobs of people running around you like holograms.

But I can’t, because of the turquoise sunbirds.

[10]

And because of the picture ( The Potato Eaters ) Van Gogh painted maybe some thirty times, each time the light falling in a different manner.

Which makes me think of the potatoes at the Austrian old age home in Ramat Gan.

My Aunt Edith and Francesca, my stepmother, saw these potatoes on blue plastic plates and sometimes their forks sparkled in the light of the light. Not to mention Mr. Cohen, who sat at another table and was a hundred years old.

As in the chorus of Beethoven’s Ninth, there wasn’t a single potato that wasn’t in its proper place.

[11]

Ezra Danischevsky did indeed become an elevator repairman, but in Los Angeles. He summoned, so I heard, Haim Gluzman, and the two of them installed elevators there.

You’re walking horizontally and suddenly you’re lifted along a vertical axis. After a while, you descend the vertical axis and go back to walking horizontally. Sometimes you’re parallel to the ground (that is, your entire body is horizontal), as when making love.

[12]

The French woman washed below her navel in the bidet and talked about Algiers, which needed (like her) to be French. Outside it was raining, and maybe love was born at the sight of her toes.

How many books have I written in order to conceal that sight, and here, at last, it’s revealed. I do now what I didn’t do then, and one by one I kiss them. From the little toe on her right foot up to the big one, and from the big toe on her left down to the little one. If there were hair on my head it would fall across the sole of her foot. May His great Name be exalted and sanctified.

[13]

My stepmother Francesca called the ground Boden . The two of us walked across the ground but, because of this other name, it (the ground) carried her differently.

There was a Mrs. Minoff, whose silk stockings every so often would develop a run (in Hebrew then they called it a “train”). Mrs. Minoff and my stepmother Francesca exchanged romance novels (in German), and sometimes they were joined in this by Mrs. Shtiasny, whose husband was Italian.

Mrs. Shtiasny’s Italian husband died suddenly in a dentist’s waiting room. The three (namely, Francesca, my stepmother, Mrs. Minoff, and Mrs. Shtiasny) stood there a good long while at the cemetery by the door to the room where the corpses are washed. My stepmother Francesca finally went in and when she came out she looked at Mrs. Shtiasny and said: Nah Yah.

[14]

In popular parlance people say “don’t make yourself out to be” this or that, but we’re always making ourselves out to be something. Only the blood flows without being told where to go (if readers would like a fine Merlot, they should look into Yiron wines).

There’s no longer any limit to the things that I (from here on in I’ll say “we,” out of embarrassment) are able to say. We can make soup from ghosts (which is to say, we can say that). We can push nails in from the wrong end. We know the difference between ourselves and others. Which is to say, others are imprisoned within their skin. We guess, for years. Paint mezuzahs. Steep tea. Grind. Herd. Toast. And on and on. We can say a single thing an infinite number of times.

Читать дальше