How, in spite of everything, the world renews itself. Phone books, for instance. Countless men and women brought together, and one could call them all.

We remember how, when we were little, maybe in sixth grade, we’d flip through the phone book and look for funny names. We found the name Dr. Ochs and called the number and when a man answered Yes (with a German accent) we said: Moooo. .

Which is how every ox finds its mate. And the male chiropractor a female chiropractor. A male accountant a woman who also manages accounts.

We remember how, in those days, we’d visit each other on Raleigh bikes (with a bell) and ride together to the river. Girls with names like Tzila would shake their heads and their braids would fly in the air. The soles of the teachers’ feet would sweat, because they were wearing leather shoes even during the summer (they’d come from the Holocaust), and if there were empty places they’d be filled up at once with oranges and tangerines.

[127]

Everyone came for a brief while and went with joy to his death.

And how did they die? One way or another. Shamaya Davidson, for instance, who was an English teacher, tried to hurdle a low barrier. Just two rows of cinder blocks. He completed the first part of the jump, which is to say, up to the point where the body begins to return to the ground. But instead of landing, he kept on rising through the air.

There was also a Hebrew teacher. He was walking down the hall and suddenly died of happiness. We’ve heard that in the old farming cooperatives people would slip between two heavy books, as though they were flowers, and press themselves dry. In Tel Aviv, people would lie (when they felt the moment was nigh) down beneath a café table, and the waiter would put a piece of cream cake on their belly.

And there were people like my grandfather, Isaac Emerich, who took off their clothes and got into bed, and thus, quietly, slept while they were dying.

[128]

We’re extremely proud of the previous chapter. It’s a shame we can’t show it to our dead relatives.

Then again, we could go to a specialist who calls the dead back to this world and speaks with them. We knew a man like that once, but he died, and now we need someone to bring him back as well. Maybe we should look in the yellow pages, under the listing “Spiritual Practice.”

Imagine that we’re trying to bring Aunt Edith back, and by mistake we summon Attila the Hun. Or Ben Gurion. What would we say? Sorry to disturb you? Better to let them be and wait until we ourselves go to them.

On the other hand, it’s possible that we’re already dead and that the world we see around us is in fact the world to come, and the government bureaus and the government itself are a kind of photographic negative of the previous world, but we just don’t know it.

Once we knew a woman who was always saying, “Oy, I’m dying.” Maybe she knew more than it seemed.

[129]

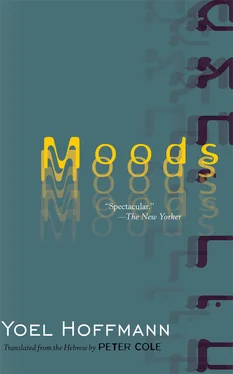

This might be the last book that we’ll write. I wonder how it will end. What its final words will be. Joyce, for example, finished his final book with the word the .

We’ve always thought it extremely strange that movies (and books) end with the word End . Moreover, sometimes the definite article’s added.

Maybe we’ll end with another word altogether. We’ll do what we did when we were little. We’ll shut our eyes and open the dictionary (or some other book) and put our finger on one of the pages and the word that our finger lands on will be the last one.

Imagine if the word turns out to be prow . Or Binyamina . Or epaulettes . Or hydraulic . Or gurgle (which is probably onomatopoeic). Or drowse . Or you .

[130]

We could, toward the end of the book, tell about a murder, and then when the woman asks, Who killed him, the detective will answer, You .

Or we could make it a love story, and the woman will ask, And who is that woman you always dream of, and the man will answer, You .

And what then? What happens in books after they end? Then, and only then, does the true story begin. Again there’s no end. No division between different things. All the colors come at once. Forms are found within each other, even if that involves a contradiction (a square circle, for instance, etcetera). Scents mix. There’s a spectrum of sounds that Maria Callas never even dreamt of. The size of the pages (after the last one) is infinite. They’re white like the Siberian tundra in winter. Whoever reads those pages reads himself to death.

[131]

Saroyan understood these things. He’d always fall toward those other pages and return (out of compassion) to the book itself. He knew the old women who sifted lentils, and the Mexican workers’ dogs.

There was never a more religious man, and therefore he drank and gambled and went to whorehouses (in books and beyond them), and every word he wrote was charged, like high tension power lines, with thousands of volts.

And he was a great thief. If we’re missing a key we can be sure it’s in the celestial pocket of his suit. He’d lift the mustache right off our face, and even slip our wife away.

In fact we’ve forgotten our name and think we’re called Saroyan. When someone says Yoel Hoffmann, we think he’s speaking to another person.

No wonder it’s so hard to separate Siamese twins. Because they have just a single heart, one of them usually dies.

[132]

Today the muses, damn them, went elsewhere. They come and go as they like, and we’re in their hands like a weather vane in the wind.

We haven’t seen them with our actual eyes, but it’s said that there are seven. And in fact, when they all come at once, the noise is unbearable. One says Write this, and another Write that, and they fight with each other and sometimes coax us into writing drivel, or worse, what’s true.

Mostly they sing like a choir of angels or those women in Hawaii who hang leis from their necks and sway their hips. But when an evil spirit gets into them, each one goes into a corner of the room and screams. And then you sink into the lowest of spirits and begin to write — like some kind of clerk — all sorts of facts. And she left. And the phone rang. And the train arrived at the station. And the street was wet with rain. And they drew pistols, etcetera etcetera.

These are the muses of sanity, destroyers of art — who tempt writers and poets to enter into a marriage with them, then send them to take out the garbage, or fix the faucet.

[133]

Dzhokhar Akhmadov, a poet from Chechnya, said to us once: You see eagles whose wingspan covers Grozny and all the surrounding plains. My elderly mother looks out through the window, but the glass is broken. Nights crawl like a hungry hyena. You’ve come from a far-off place and so my soul grows faint. Have you ever seen a Muslim cloud? Or a cloud that’s Greek Orthodox?

People died of tuberculosis. Some in stairwells, with fire from the bombs lighting up their faces. I didn’t know you before today, but I’ve long known you would come, and now we can go to a single grave. You see these hands? Think of an infant and think of a mortar.

[134]

As though in a slaughterhouse, we need to strip off all of our skin — down to the very last piece. We’re the butcher and also the beast. And if the blood doesn’t flow toward the drainage channels, there is no literature and there is no poetry.

Once we sat in a Tel Aviv café (we realize there’s more to Tel Aviv than cafés, but when we go there we’ve nowhere to sleep), and we saw through the glass a woman pushing a carriage and in the carriage there was a baby. Where is that woman now? And the baby?

Poetry’s found in the melting tar of summer rooftops, in which you can see the imprint of the soles of shoes.

Читать дальше