“You should see your face,” she said to me.

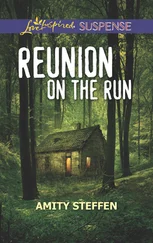

“I have some things—,” I said. “Some things in the cabin—”

“So what?” April said. “They’re gone. They’re not yours anymore.”

Meadow was staring at me. Her face must have mirrored mine, if only because mine frightened her so much. That’s when I thought of it, of what I had left to do.

“Get in, sweetheart,” I said.

“And don’t slam the door,” added April.

“Be quiet.”

“Why, Daddy? What’s wrong?”

“Get in .”

And there they were — male voices, down by the water, amplified by the lake, sounding closer than they were. They sounded as if they were right beside us on the road, invisible men. The dogs were barking out of their minds.

I couldn’t buckle my seat belt. I couldn’t feel my fingers. I tried and tried. We were already moving very fast by then.

The road for all seasons and reasons,” Route 2 sweeps you through Vermont’s niche industries, a series of diverse, minor attractions like the winery at Calais or the “cornfusing” corn maze at Danville. And if the traveler doesn’t have time to stop, if he is, in fact, desperately trying to cross state lines, he may just gaze out the car window at the legendary Vermont woodland, through which, if he lives that long, the traveler may return on a charter bus from his retirement home in some distant leaf-peeping season. And if he closes his eyes, he can see it already, although it is only June: autumn’s mosaic of yellow and copper and red, the sad magic of it.

Meadow had not spoken a word to me since the outskirts of Burlington. She sat steely eyed in the backseat, her hands clutched in her lap, looking small and unfamiliar without the added height of her booster seat. I had tried to speak to her several times, but at the sound of my voice she snapped her head to the side. She’d been upset to abandon her backpack (“and my tooth brush and my new bi ki ni”). All she now possessed, in fact, was an empty bucket. As for me, I carried only my wallet and keys and the clothes I’d been wearing for four days — a pair of flat-fronted khakis, still rolled to the knee and wet with pond water, and a blue-checkered collared shirt with a wilted buttercup in the breast pocket. Everything else in our cabin was currently being turned inside out by some square-jawed woodhick with a CB radio. ( Found something, Dawson .) Of course, at the core of this, there was an image that made my stomach tighten. ( What is it, Peterson? Looks like a passport. ) I saw him coming toward me — not the cop, the boy — in his knee-high athletic socks, his knockoff Bruins jersey, circling me like some hungry fish.

Erik Schroder, it says. Who the hell is Erik Schroder?

“What’s that sign mean?” Meadow said suddenly, pointing out the window.

We were driving through a mountain pass of blasted granite.

I cleared my throat, trying to summon a steady voice. “Falling rock.”

“Oh great,” Meadow said. “Now rocks are going to fall on us, too?”

The wind was high, swabbing the clouds back and forth across the sun. Whenever we plunged into shadow, Meadow’s eyeglasses became reflective, giving her face a cold, mechanical look.

“April’s driving too fast,” she muttered. “She’s driving too fast to miss the falling rocks.”

“Hey,” April said into the rearview mirror. “As my mother used to say, don’t should on me, and I won’t should on you.”

Meadow crossed her arms and snapped her head to the side again. “I don’t care what your mother used to say.”

We plunged back into silence. Probably none of us, in our whole lives, had ever gone so long without talking. I glanced over at April, who was holding on to the steering wheel with a high two-handed grip like an old lady. Was I that bad, was I that desperate, to become the goodwill case of a woman like her?

“Hey, April,” Meadow said darkly.

“Yeah, hon?”

“Chrissy’s not my real name.”

April laughed. “I didn’t think it was, honey.”

I didn’t turn around.

“My name is Meadow. Meadow Kennedy.”

“Well,” said April, “my name really is April Almond. Even though it sounds made up.” She laughed again, this time a little uncomfortably. “Funny how people are always trying to tell me the truth, even when they shouldn’t.”

“My daddy doesn’t always tell the truth. He tried to shut me in the trunk of a car once.”

I swung around. “What?”

“You did .”

“But I didn’t . I mean, I didn’t shut you in it. And besides, I’ve apologized for that several times.” I looked at April. “I apologized for that.”

“Don’t tell me about it,” said April.

“And Mommy said you lied sometimes.”

“When?”

“When I was little. And you took me all sorts of places.”

“Like the library ? When I was taking care of you? And she was at work ?”

“No. Like the church where everybody was crying? Mommy said that was not for kids.”

Again I turned to April. “An AA meeting. I went to support a friend.”

“You took her to an AA meeting?”

“A mistake.”

“Well, I told Mommy all about it,” Meadow declared.

“You can’t tell Mommy things like that, Meadow. She doesn’t understand them out of context.”

“Still!” Meadow shrieked. “You’re not supposed to lie. If it was good you would have told!”

“All right, all right,” April said. “You know what? I really don’t want to know any more about all this. I’m sure you are both very important people. You deserve a ticker-tape parade for living, OK? Anyway, cheer up. We’re heading to New Hampshire, a great state. We’ll drive over the Kancamagus. Gorgeous. You won’t believe it. Much better than this. The White Mountains blow the Green Mountains out of the water. Who wants to listen to the radio?”

She screwed irritably at the dials. In the distance, mountains tumbled into mountains. The nearest ranges were dark and green, the farther ranges fainter and higher, echoed by fainter mountains farther still, the jagged horizon a series of studies for a mountain.

“I want to thank you,” I said to April, my voice thick and wounded. “You’ve been — you’ve been—”

“No problem. You’re welcome.”

“I’m not a bad person.”

April sighed. “You may or may not be a bad person. You’re just a lot less bad than the other people I know.”

“Well, thanks.”

“Like I said.”

“I mean, thanks for taking us to your place. I just need a quiet place to stay. To collect my thoughts.”

“You won’t be staying anywhere, John.” April turned and looked at me hard. Then she glanced backwards at Meadow, who was scrutinizing us from behind. Finally, Meadow rolled her head away and pretended to stare at the landscape. April turned up the volume on the radio. “And I didn’t say the place was mine. The place is my cousin’s. A camp near Ragged Mountain.”

“No, listen. I don’t want to involve anyone else.”

“My cousin’s not there. It’s a long story, but let’s just say he’s in Georgia. I check in on his place now and again.”

“Better to stay at a motel. You can drop us off at any motel.”

“Slow down. At my cousin’s place, you’ll have privacy. You can give her a home-cooked meal, and you can think about where to go next. But you won’t be able to stay anywhere, is all I’m saying. I mean, if your idea is that you’re going to keep running. With or without her. There are lots of people out there living like that.” She dropped her voice to a whisper. “Jesus. I’m not going to force your hand. But she will. Look at her.”

Читать дальше