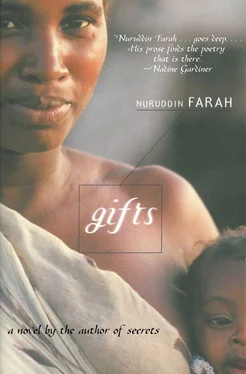

Nuruddin Farah - Gifts

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nuruddin Farah - Gifts» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gifts

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gifts: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gifts»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gifts — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gifts», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

There is a tradition, in Somalia, of passing round the hat for collections. It is called Qaaraan. When you are in dire need of help, you invite your friends, relatives and in-laws to come to your place or someone else’s, where, as the phrase goes, a mat has been spread. But there are conditions laid down. The need has to be genuine, the person wishing to be helped has to be a respectable member of society, not a loafer, a lazy ne’er-do-well, a debtor or a thief. Here discretion is of the utmost significance. Donors don’t mention the sums they offer, and the recipient doesn’t know who has given what. It is the whole community from which the person receives a presentation and to which he is grateful. It is. not permitted that such a person thereafter applies for more, not soon at any rate. If there is a lesson to be learned from this, it is that emergencies are one-off affairs, not a yearly excuse for asking for more. Now how many years have we been passing round the empty bowl?

Famines awake a people from an economic, social or political lethargy. We’ve seen how the Ethiopian people rid themselves of their Emperor for forty years. Foreign food donations create a buffer zone between corrupt leaderships and the starving masses. Foreign food donations also sabotage the African’s ability to survive with dignity. Moreover, it makes their children feel terribly inferior, discouraging them from eating the emaciated bean sprouts, the undernourished corn-on-the-cob and broken rice. Forgive me for dishing out to you cliches and, if I may beg your indulgence, let me quote a statement made by Hubert Humphrey, who said in 1957, “I’ve heard … that people may become dependent on us for food. I know this is not supposed to be good news. To me that was good news, because before people can do anything, they have got to eat. And if you are looking for a way to get people to lean on you and to be dependent on you, in terms of their co-operation with you, it seems to me that food dependence would be terrific.” Well put, wouldn’t you agree? Now we may continue.

An East African leader, known to be of socialist persuasion, recently granted an interview to a London-based African magazine, in which he said that the developed nations must help Africa. But why must they? What makes him think that the African has a proprietory right over the properties of others? Did the country of which he has been a leader the past quarter of a century donate generously to the starving in Ethiopia or Chad? One could understand if this most respected African statesman made his statement in the context of a familiar or tribal society where obligatory or voluntary exchanges of gifts are part of the code of behaviour. In such a context, the exchange is direct. You give somebody something; a year later, when you are in need, today’s recipient becomes tomorrow’s giver. Does this intellectual statesman foresee the time when Africa will be in a position to donate food to Europe, North America or Japan? Is he aware that he is turning the African into a person forever dependent?

Every gift has a personality — that of its giver. On every sack of rice donated by a foreign government to a starving people in Africa, the characteristics and mentality of the donor, name and country, are stamped on its ribs. A quintal of wheat donated by a charity based in the Bible Belt of the USA tastes different from one grown in and donated by a member of the European Community. You wouldn’t disagree, I hope, that one has, as its basis, the theological notion of charity; the other, the temporal, philosophical economic credo of creating a future generation of potential consumers of this specimen of high quality wheat. I have two problems here.

One. It is my belief that a god-fearing Bible Belter knows that publicized charities won’t wash with God. The only mileage in it is an earthly sense of vainglory. Second. The European Community bureaucrat need not be told that the donated wheat is but a free sample of items that it is hoped will sell very well when today’s starving Africans become tomorrow’s potential buyers. There is enough literature to fill bookcases, surveys written up by scholars, following America’s policy of donating food aid to Europe, Japan, South-East Asia. I suggest that you walk this well-trodden path in the company of Susan George or Teresa Hayter. But let me deal with the mentality of the receiver and his systems of beliefs and what gifts mean to him.

Most Africans are (paying?) members of extended families, these being institutions comparable to trade unions. Often, you find one individual’s fortunes supporting a network of the needs of this large unit. On a psychological level, therefore, we might say that the African is unquestionably accustomed to the exchange of potlachs. Those who have plenty, give; those who have nothing to give, expect to be given to. In urban areas, there are thousands of strong young men and women who receive “unemployment benefit” from a member of their extended family, somebody who has a job. Hence, it follows that when the bread-winner’s earnings do not meet everyone’s needs; when the land isn’t yielding, because insufficient work is being put in to cultivate it; when hard currency-earning cash crops are grown and the returns are paid to service debt; and just when the whole country is preparing to rise in revolt against the neo-colonial corrupt leadership: a ship loaded with charity rice, unasked for, perhaps, docks in the harbour — good quality rice, grown by someone else’s muscles and sweat. You know the result. Famine (my apologies to Bertold Brecht) is a trick up the powerful man’s sleeve; it has nothing to do with the seasonal cycles or shortage of rain.

If I could afford to be cynical, I would say that the African, knowing no better, accepts whatever he is given because it is an insult to refuse what you’re offered. If his cousin or a member of the extended family doesn’t give, God will or somebody else will. God, as we know Him, has been “given” to us, together with all the mythological paraphernalia, genealogical truisms that classify us inferior beings, not to forget the Middle Eastern philosophical maxim that God (in a monotheistic sense) is progress. Yes, the truth is, our Gods and those of our forefathers, we have been told, do not give you anything; and since they have a beginning, they have an end, too.

Somalis are of the opinion that it is in the nature of food to be shared. If you come upon a group of people eating, you are invited to join them. There is, of course, the prophylactic tendency to avoid the wickedness of the envious eye of the hungry, but this isn’t the principal reason why you’re offered to partake of the meal being eaten. Linked to the notion of food is the belief regarding the shortlived nature of all perishables. The streets of Mogadiscio are overcrowded with beggars carrying empty bowls, wandering from door to door, begging to be given the day’s left-overs. Is it possible, I wondered the other day, to equate the donor governments’ food surpluses which are given to starving Africans, to the left-overs we offer to famished beggars? Or am I stretching the point?

When Somalis despair of someone whom they describe as a miser, they often say, “So-and-So doesn’t give you even a glass of water.” So when they hear stories about butter being preserved in icy underground halls, foods kept in temperatures below freezing point, racks and racks of meat shelved, rows and rows of rice and other luxuries kept in a huge cellar colder than the Arctic, it is then that Somalis say, “But these people are mean.” Press them to tell you why they should be given anything, and they take refuge in generalizations. Ask them why Russia doesn’t provide them with food aid, and they become cynical. The only difference between us and Russia, although we eat the same American wheat, is that we pay for it with our begging, and they with their foreign reserves.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gifts»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gifts» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gifts» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.