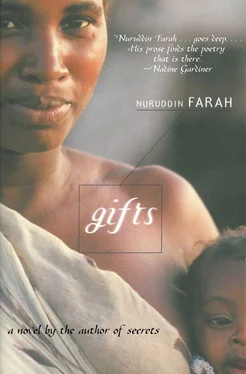

Nuruddin Farah - Gifts

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Nuruddin Farah - Gifts» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Arcade Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gifts

- Автор:

- Издательство:Arcade Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gifts: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gifts»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Gifts — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gifts», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And then Bosaaso came to fetch her. It was early afternoon.

On meeting him she said that she felt hungry all day and yet had not really wanted to eat, for she had no appetite. Or maybe she wasn’t expressing herself well? Bosaaso surmised that eating was an undertaking for its own sake. He cited as an example the weeks following Yussur’s and his son’s tragic deaths when he gave up smoking. He also remembered how empty he had felt as soon as he finished defending his PhD thesis. He had been so restless he could only fill the vacuity he sensed in his soul with work, more work. It was then that the idea came to him.

“ We’re going out to dinner tonight,” he said.

Smiling condescendingly, she said, “Who are we, may I ask?”

“You and I, of course.”

A long instant passed before she realised that his presence had a pleasant effect, and she was not feeling all that vacuous; rather she felt as if she were filled with aspects of him. “And where are we going?” she asked.

“I know a good restaurant.”

“See you shortly,” she said.

He offered to come for her at about seven.

Duniya’s feeling of weightlessness returned directly she was alone, so that she had to lean against the outside door once she opened it. She remained where she was until her chest rose, with her breathing, her heart beating faster in anticipation of self-hatred, a notion which nauseated her. Or was it love? Whichever it was, she wished to have nothing to do with it. Surely to be affected by such a nebulous sensation of sickness is no love, or is it? Her self-questioning inspired courage in her and she was able to walk through the entrance, her gait uncertain, her whole body numbed by worry.

She unlocked the door to the room she shared with Nasiiba and brought out a chair; perhaps if she stayed still, the fog in her mind would clear. But she couldn’t remain at peace with herself; it was as though her brain carried with it seeds which suddenly broke, bringing forth a baobab tree in full bloom. She thought that the previous week’s events had planted seedlings sown to germinate, something that would happen sooner or later, but the foundling who had been the seedsman was no longer there.

Duniya’s thoughts were chaotic and in a state of upheaval until the door opened, letting in someone with steps soft as weak applause. The tense look in her eyes as she welcomed Nasiiba with a smile belied her true feelings. Contradictory emotions were disguised by the defiant grin that defined Duniya’s features as she and her daughter touched, as they kissed. As usual the young woman was full of life, bursting with the desire to make something happen. She was visibly sad that the foundling had died, but that didn’t deter her from investing her energies either in herself or her mother. “What’s happening, Mummy?” she asked.

Duniya felt very restless today and she got up, her cheeks feeling warm. She couldn’t decide what to tell Nasiiba and what not to; a great deal was happening, and not all of it was good or bad, or even easy to explain. Love was happening, for instance. Nausea was taking place, for example. She gave as reassuring a smile as she was capable of and then said “We’re going to dinner, Bosaaso and I.”

Nasiiba said, “We’re going out to a restaurant, are we?”

Duniya decided that Nasiiba’s use of the first person plural was essentially different from her own, realizing, as though for the first time, that the pronoun had such a wealthy set of associations. It was like learning a new language. Presently, Duniya was attended by the pleasant remembrance that at the mention of Bosaaso’s name all her vertiginous sensations were gone. She felt anchored, her soul cast in its intention to pursue its destiny, its happiness.

“We must dress up, mustn’t we then?” said Nasiiba.

Duniya stood in the sadness of a shock she hadn’t anticipated. The truth was she hadn’t thought of dressing up for the occasion, she hadn’t the calmness of mind to prepare herself for the changes that were taking place around her, as well as inside her. She now gripped the chair nearest her, glancing at Nasiiba’s direction, and recognizing the need to put herself in her daughter’s hands; in essence, admit that she was in love.

Her tone of voice not unlike a very young girl trying on her mother’s high-heel shoes, Duniya said, “How about if I shower first? Don’t you think that’s a good idea? In the meantime you may choose the dress you want me to try on.”

“What a wonderful idea,” said Nasiiba rather excitedly.

Sunlight glared wickedly on her eyes, and she grinned. Things were much more complicated than she imagined, and no giving was innocent. What was it Nasiiba had said? That she would help dress her? Duniya was distressed at the thought of her daughter asking her to undress, to stand naked in front of her, to pirouette before deciding how she should dress. She now stood in a posture of intense self-questioning, wondering what to do. She was wrapped in the folds of a robe, fully clothed, save for her head whose curls shone from being hastily shampooed but fully rinsed.

Nasiiba said, “I’ve shut the outside door and we’re as private as we are likely to be. What I want you to do is to step out of your puritanical robe so I can take a good look at what you’ve got by way of a body. We haven’t much time, so please hurry.”

Staggered, Duniya said, “You can’t be serious?”

“I am,” Nasiiba assured her.

“I am your mother,” Duniya reminded her.

Nasiiba looked in the general direction of the door to the room they shared. “I’m your daughter, need I remind you, and in any case, I’ve seen you naked or part-naked many times. So what’s the fuss? Let’s get on with it.”

Duniya’s memory was haunted by the thought that Nasiiba had seen her totally naked and making love to Taariq, as she had learned a couple of nights before. Her voice laced with pauses of self-doubt, she inquired, “What’s that on the back of the chair?”

“The dress I want you to try on.”

If she knew how, Duniya would have brought the whole charade to an end. Did Nasiiba think that because she had presented her with a dress or because Duniya had accepted to be dressed up, the young woman could request that her mother undress?

“You’re no shrine,” said Duniya, “and I’m not making an offering of my body.” So saying, she turned her back on Nasiiba but she failed to take one single step away, as though incapable of understanding the significance of her decision. She was weighed down by a sadness of heart because all loving thoughts were for the instant absent from her. She was close to making an appeal to let her be when Nasiiba suggested anew that she undress.

Somehow Duniya came to realise there was no turning back and what had to be done had to be done, reminding herself that the twin’s father, being blind, had never set eyes on her body, and that it was ironic now that his daughter was undressing her. She also drew strength from the memory that she, as a midwife, had seen many a woman naked, women whose bodies she had handled, whose most private parts she touched with panache. Her gaze worried, her body trembling, she flung aside the robe with which she had been covered, saying, “There you are,” speaking the words with flamboyance.

Nasiiba’s judgement came quickly: “Not bad at all.”

Duniya, for her part, was too tongue-tied to say anything. The one good thing this humiliation was achieving for her was that she was becoming heavy like a club-foot, no fear of flying away from weightlessness. This caused a kind of acrimony to grow within her, but she was certain the feeling would vanish and she and Bosaaso would once again be united — and in love.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gifts»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gifts» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gifts» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.