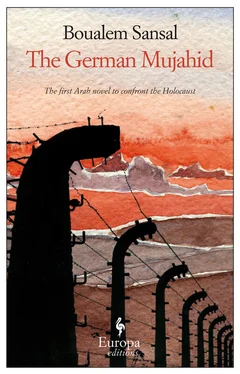

It had stopped snowing. The wind had died away. The cold was not so biting. A small unseen sun brought a faint warmth. Perhaps only one degree, but to me it felt like a breath of life. I got to my feet. I ached all over. I stretched and continued to wander around the camp. I wanted to go back to the station, all things considered it is the most important place in the camp, the most cruel, the place where everything is decided. It was here that the men, the women, the terrified children, the babies sleeping in their own filth arrived at the end of the line. They are still dressed as they were in the city, they carry a suitcase, a bag, a briefcase, a toy, the women carry their babies, hug them to their breasts, fingertips gently stroking their cheeks, sheltering them from the cold, from the sun, they have their papers on them, their watches, their jewellery, money in their pockets. And that yellow star on the lapels of their jackets, true, the Judenstern , a badge of shame, but it signifies only that they are Jews; it is possible to dislike them, it doesn’t matter, no one can be expected to like everyone. Others are shamefaced, the Gypsies, the dark-skinned people, the sick, with their strange pallor and their frail voices, the old men and women pitiful to see so far from the life they once led, and what of the children who can neither grow up nor pretend to be grown-ups nor understand what is going on around them, what is being done to their parents. But this station is not like any station in the world. And this star is not like any star in the heavens. It is here, on the Judenrampe , on this wasteland around the station, that the selection took place, that they were separated, registered, tattooed, where they dressed in camp clothes, lined up, and here they waited for someone, some deus ex machina beset by terrible fears, some Bonzen , to give the order. They wait for hours and every minute is endless. For the old, the sick, the children, this is where it ends. They will see no other day. They do not know it, some of them suspect, but something that has not yet happened, something you have not seen with your own eyes is simply a speculation, life is still possible: the doors to the gas chambers are already open and the Sonderkommandos are waiting for them, standing to attention, by their wheelbarrows, the stench of rotting flesh and the stony silence helping them to forget what they have come to. In a few hours, they will be smoke rising into God’s heaven, the deaf, blind, cruel God to whom they have been praying all their lives. How is it possible to believe in such a God? A cat, a rat, a cold-blooded snake affords humanity more warmth. It is a life rubbing up against another life. For the able-bodied men and women, this is where it begins. In this place they are forever stripped of their autonomy, their dignity, their memories, their humanity. Everything. It is at this moment that they truly become Abgewandert. Death is a formality that will come later, when they earn it through good, honest work.

She was standing at the gates of Birkenau. A frail old woman, her legs slightly bowed, a handbag dangling from her elbow, wearing a ridiculous little hat. Her coat had seen better days and was shiny with wear. She stood alone, motionless, staring fixedly at something in front of her feet. She looked like an elderly housekeeper standing at a bus stop in a chalk white, windswept housing estate waiting for the first bus of the morning. She glanced left and right, then turned again and for a long time she stared at the train tracks that stretched out towards the horizon, at the banks on either side, at the sky wrapped up warm in its heavy clouds, before turning to look again at the building and the watchtower. She took in every detail. I could feel something inside her cry out as she stood frozen before this threshold which was once crossed only to die. She steeled herself and walked forward under the archway where she stopped dead — I think even her breath stopped. Her head jerked from side to side as though twisted by some malfunctioning machine. It was fear, the all-consuming fear that is Auschwitz. I stood transfixed by this strange, piteous ballet in this theatre of horrors beneath a sky which left room only for grief and silence. I could tell that she was searching her memory, searching for landmarks, reference points. Memories. She stood, thinking. I would say that she was feeling things inwardly, evil and its mysteries scattered by time, she moved like an animal that instinctively senses the reverberations of some distant earthquake and begins to panic. But she, she did not move, no longer moved, she looked as though she could stand there forever, waiting. Then she shuddered, and, as though resolved to face her suffering, stepped through the entrance into the camp, a single step, then stopped again. She scanned the place, then turned to her right and, taking small steps, walked slowly, her head down. She had stepped into another world, this world I know so well on paper I could guide her, predict her every reaction in advance. I realised that she had lived here in this loathsome place. How I knew, I’m not sure, but in her I saw a star in my dark sky. I followed her.

She went into the women’s Lager. She stopped, took a handkerchief from her bag, rolled it into a ball, wiped her eye then pressed it to her nose. She moved forward, read the number on the first block, then the next, and the next. She was walking faster now, darting ahead in jerky little steps, the block she was looking for was not far. Then she stopped and for a long time she stared at the block on her right, then stepped towards the entrance, climbed the three steps, reached out and put her hand on the doorknob. She hesitated, then turned it first one way, then the other. The door was locked. She did not try again. She sat down on the top step. I watched her. She did nothing, she did not move. She was off somewhere in her mind, in some dark place. I felt a surge of affection for this woman. She seemed so frail, so alone.

I hid in the shadows so I could watch her. Head tilted to one side, she was toying with her handkerchief in her lap, folding and unfolding it, rolling it into a ball and unrolling it again. In her mind, I thought, she was very far away. After half an hour, she got up, gave a little sigh and headed east towards the gas chambers and the crematorium. There was a crowd. Tourists. A group of kids, schoolchildren, and an adult group. They were listening to their respective guides. The kids were taking photographs, whispering to each other. What they wanted was to shout, to ask real questions, but this was not a place where conversation was customary, those who came here were gassed, incinerated, rose in a column of smoke, they knew that. The older group said nothing, they stood motionless. The woman joined the older group. She said something to the man standing next to her, who put his arm around her shoulder and kissed her on the forehead. The gesture of a friend. I joined the group. The guide was talking, explaining. I didn’t like his voice, there was something wrong about the tone. What irritated me was that he was trapped in his books, in his technical reports, what he was describing was a process. That is not what extermination is! Not just that. It cannot be brought down to its final act. There is everything else, the most important part, the part that is nameless, the everyday evil that you quickly grow accustomed to, that you never grow accustomed to, that thing which the old woman instinctively understood, that thing that I have been trying desperately to understand for months without even coming a fraction of an inch closer. I had felt this from the first: I could know my father, know myself, by following his path to the end, to the heart of the Machine. But no knowledge, no insight, no compassion, no imagination can achieve what experiencing the genocide has etched on the minds of the prisoners, and they, the survivors, have no means of communicating it to us. My father will forever be a mystery, and my pain will know no end.

Читать дальше