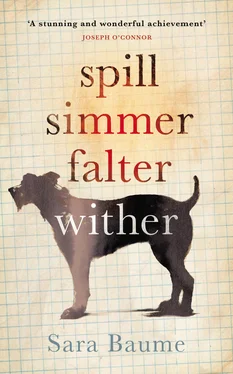

Sara Baume

Spill Simmer Falter Wither

You find me on a Tuesday, on my Tuesday trip to town. A note sellotaped to the inside of the jumble-shop window: COMPASSIONATE & TOLERANT OWNER. A PERSON WITHOUT OTHER PETS & WITHOUT CHILDREN UNDER FOUR.

A misfit man finds a misfit dog. Ray, aged fifty-seven, ‘too old for starting over, too young for giving up’, and One Eye, a vicious little bugger, smaller than expected, a good ratter. Both are accustomed to being alone, unloved, outcast — but they quickly find in each other a strange companionship of sorts. As spring turns to summer, their relationship grows and intensifies, until a savage act forces them to abandon the precarious life they’d established, and take to the road.

Spill Simmer Falter Wither is a wholly different kind of love story: a devastating portrait of loneliness, loss and friendship, and of the scars that are more than skin deep. Written with tremendous empathy and insight, in lyrical language that surprises and delights, this is an extraordinary and heart-breaking debut by a major new talent.

Sara Baume was born in Lancashire and grew up in Co. Cork. She studied fine art and creative writing and her short fiction has been published in journals such as The Stinging Fly magazine and the Dublin Review. She won the 2014 Davy Byrnes Short Story Award and the 2015 Hennessy New Irish Writing Award. She now lives in Cork with her two dogs.

Spill Simmer Falter Wither

He is running, running, running.

And it’s like no kind of running he’s ever run before. He’s the surge that burst the dam and he’s pouring down the hillslope, channelling through the grass to the width of his widest part. He’s tripping into hoof-rucks. He’s slapping groundsel stems down dead. Dandelions and chickweed, nettles and dock.

This time, there’s no chance for sniff and scavenge and scoff. There are no steel bars to end his lap, no chain to jerk at the limit of its extension, no bellowing to trick and bully him back. This time, he’s farther than he’s ever seen before, past every marker along the horizon line, every hump and spork he learned by heart.

It’s the season of digging out. It’s a day of soft rain. There’s wind enough to tilt the slimmer trunks off kilter and drizzle enough to twist the long hairs on his back to a mop of damp curls. There’s blood enough to gush into his beard and spatter his front paws as they rise and plunge. And there’s a hot, wet thing bouncing against his neck. It’s the size of a snailshell and it makes a dim squelch each time it strikes. It’s attached to some gristly tether dangling from some leaked part of himself, but he cannot make out the what nor the where of it.

Were he to stop, were he to examine the hillslope and hoof-rucks and groundsel and dandelions and chickweed and nettles and dock, he’d see how the breadth of his sight span has been reduced by half and shunted to his right side, how the left is pitch black until he swivels his head. But he doesn’t stop, and notices only the cumbersome blades, the spears of rain, the upheaval of tiny insects and the blood spilling down the wrong side of his coat, the outer when it ought to be the inner.

He is running, running, running. And there’s no course or current to deter him. There’s no impulse from the root of his brain to the roof of his skull which says other than RUN.

He is One Eye now.

He is on his way.

You find me on a Tuesday, on my Tuesday trip to town.

You’re sellotaped to the inside pane of the jumble shop window. A photograph of your mangled face and underneath an appeal for a COMPASSIONATE & TOLERANT OWNER. A PERSON WITHOUT OTHER PETS & WITHOUT CHILDREN UNDER FOUR. The notice shares street-facing space with a sheepskin overcoat, a rubberwood tambourine, a stuffed wigeon and a calligraphy set. The overcoat’s sagged and the tambourine’s punctured. The wigeon’s trickling sawdust and the calligraphy set’s likely to be missing inks or nibs or paper, almost certainly the instruction leaflet. There’s something sad about the jumble shop, but I like it. I like how it’s a tiny refuge of imperfection. I always stop to gawp at the window display and it always makes me feel a little less horrible, less strange. But I’ve never noticed the notices before. There are several, each with a few lines of text beneath a hazy photograph. Altogether they form a hotchpotch of pleading eyes, foreheads worried into furry folds, tails frozen to a hopeful wag. The sentences underneath use words like NEUTERED, VACCINATED, MICROCHIPPED, CRATETRAINED. Every wet nose in the window is alleged to be searching for its FOREVER HOME.

I’m on my way to purchase a box-load of incandescent bulbs because I can’t bear the dimness of the energy savers, how they hesitate at first and then build to a parasitic humming so soft it hoaxes me into thinking some part of my inner ear has cracked, or some vital vessel of my frontal lobe. I stop and fold my hands and examine the fire-spitting dragon painted onto the tambourine’s stretched skin and the wigeon’s bright feet bolted to a hunk of ornamental cedar, its wings pinioned to a flightless expansion. And I wonder if the calligraphy set is missing its instruction leaflet.

You’re sellotaped to the bottommost corner. Your photograph is the least distinct and your face is the most grisly. I have to bend down to inspect you and as I move, the shadows shift with my bending body and blank out the glass of the jumble shop window, and I see myself instead. I see my head sticking out of your back like a bizarre excrescence. I see my own mangled face peering dolefully from the black.

The shelter is a forty-minute drive and three short, fat cigarettes from home. It occupies a strip of land along the invisible line at which factories and housing estates give way to forests and fields. There are rooftops on one side, treetops on the other. Concrete underfoot and chainlink fencing all around, its PVC-coated diamonds rattling with the anxious quivers of creatures MISTREATED, ABANDONED, ABUSED. Adjacent to the diamonds, there’s a flat-headed building with unsound walls and a cavity block wedged under each corner. A signpost rises from the cement. RECEPTION it says, REPORT ON ARRIVAL.

I’m not the kind of person who is able to do things. I don’t feel very good about climbing the steps and pushing the door, but I don’t feel very good about disobeying instructions either. My right hand finds my left hand and they hold each other. Now I step up and they knock as one. The door falls open. Inside there’s a woman sitting behind a large screen between two filing cabinets. There’s something brittle about her. She seems small in proportion to the screen, but it isn’t that. It’s in the way the veins of each temple rise through her skin; it’s in the way her eyelids are the colour of a climaxing bruise.

‘Which one?’ she says and shows me a sheet of miniature photographs. As I place the tip of my index finger against the tip of your miniaturised nose, she ever-so-slightly smiles. I sign a form and pay a donation. The brittle woman speaks into a walkie-talkie and now there’s a kennel keeper waiting outside the flat-headed office. I hadn’t imagined it might be so uncomplicated as this.

He’s a triangular man. Loafy shoulders tapering into flagpole legs, the silhouette of a root vegetable. He’s carrying a collar and leash. He swings them at his side and talks loudly as he guides me through the shelter. ‘That cur’s for the injection I said, soon’s I saw him, and wouldn’cha know, straight off he sinks his chompers into a friendly fella’s cheek and won’t let go. There he is, there.’

Читать дальше