Opposing the movement of the peasant’s thoughts and feelings about a justice in the past are other thoughts and feelings directed towards the survival of his children in the future. Most of the time the latter are stronger and more conscious. The two movements balance each other only in so far as together they convince him that the interlude of the present cannot be judged in its own terms; morally it is judged in relation to the past, materially it is judged in relation to the future. Strictly speaking, nobody is less opportunist (taking the immediate opportunity regardless) than the peasant.

How do peasants think or feel about the future? Because their work involves intervening in or aiding an organic process most of their actions are future-oriented. The planting of a tree is an obvious example, but so, equally, is the milking of a cow: the milk is for cheese or butter. Everything they do is anticipatory — and therefore never finished. They envisage this future, to which they are forced to pledge their actions, as a series of ambushes. Ambushes of risks and dangers. The most likely future risk, until recently, was hunger. The fundamental contradiction of the peasant’s situation, the result of the dual nature of the peasant economy, was that they who produced the food were the most likely to starve. A class of survivors cannot afford to believe in an arrival point of assured security or well-being. The only, but great, future hope is survival. This is why the dead do better to return to the past where they are no longer subject to risk.

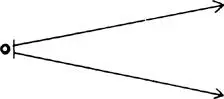

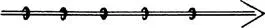

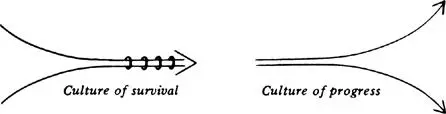

The future path through future ambushes is a continuation of the old path by which the survivors from the past have come. The image of a path is apt because it is by following a path, created and maintained by generations of walking feet, that some of the dangers of the surrounding forests or mountains or marshes may be avoided. The path is tradition handed down by instructions, example and commentary. To a peasant the future is this future narrow path across an indeterminate expanse of known and unknown risks. When peasants cooperate to fight an outside force, and the impulse to do this is always defensive, they adopt a guerrilla strategy — which is precisely a network of narrow paths across an indeterminate hostile environment.

The peasant view of human destiny, such as I am outlining, was not, until the advent of modern history, essentially different from the view of other classes. One has only to think of the poems of Chaucer, Villon, Dante; in all of them Death, whom nobody can escape, is the surrogate for a generalized sense of uncertainty and menace in face of the future.

Modern history begins — at different moments in different places — with the principle of progress as both the aim and motor of history. This principle was born with the bourgeoisie as an ascendant class, and has been taken over by all modern theories of revolution. The twentieth-century struggle between capitalism and socialism is, at an ideological level, a fight about the content of progress. Today within the developed world the initiative of this struggle lies, at least temporarily, in the hands of capitalism which argues that socialism produces backwardness. In the underdeveloped world the “progress” of capitalism is discredited.

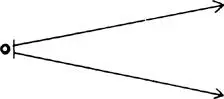

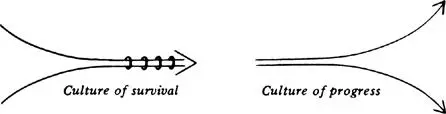

Cultures of progress envisage future expansion. They are forward-looking because the future offers ever larger hopes. At their most heroic these hopes dwarf Death ( La Rivoluzione o la Morte! ). At their most trivial they ignore it (consumerism). The future is envisaged as the opposite of what classical perspective does to a road. Instead of appearing to become ever narrower as it recedes into the distance, it becomes ever wider.

A culture of survival envisages the future as a sequence of repeated acts for survival. Each act pushes a thread through the eye of a needle and the thread is tradition. No overall increase is envisaged.

If now, comparing the two types of culture, we consider their view of the past as well as the future, we see that they are mirror opposites of one another.

This may help to explain why an experience within a culture of survival can have the opposite significance to the comparable experience within a culture of progress. Let us take, as a key example, the much proclaimed conservatism of the peasantry, their resistance to change; the whole complex of attitudes and reactions which often (not invariably) allows a peasantry to be counted as a force for the right wing.

First, we must note that the counting is done by the cities, according to an historical scenario opposing left to right, which belongs to a culture of progress. The peasant refuses that scenario, and he is not stupid to do so, for the scenario, whether the left or right win, envisages his disappearance. His conditions of living, the degree of his exploitation and his suffering may be desperate, but he cannot contemplate the disappearance of what gives meaning to everything he knows, which is, precisely, his will to survive. No worker is ever in that position, for what gives meaning to his life is either the revolutionary hope of transforming it, or money, which is received in exchange against his life as a wage earner, to be spent in his “true life” as a consumer.

Any transformation of which the peasant dreams involves his re-becoming “the peasant” he once was. The worker’s political dream is to transform everything which up to now has condemned him to be a worker. This is one reason why an alliance between workers and peasants can only be maintained if it is for a specific aim (the defeat of a foreign enemy, the expropriation of large landowners) to which both parties are agreed. No general alliance is normally possible.

To understand the significance of peasant conservatism related to the sum of peasant experience, we need to examine the idea of change with a different optic. It is an historical commonplace that change, questioning, experiment, flourished in the cities and emanated outwards from them. What is often overlooked is the character of everyday urban life which allowed for such an interest in research. The city offered to its citizens comparative security, continuity, permanence. The degree offered depended upon the class of the citizen, but compared to life in a village, all citizens benefited from a certain protection.

There was heating to counteract changes of temperature, lighting to lessen the difference between night and day, transport to reduce distances, relative comfort to compensate for fatigue; there were walls and other defences against attack, there was effective law, there were almshouses and charities for the sick and aged, there were libraries of permanent written knowledge, there was a wide range of services — from bakers and butchers through mechanics and builders to doctors and surgeons — to be called upon whenever a need threatened to disrupt the customary flow of life, there were conventions of social behaviour which strangers were obliged to accept (when in Rome …), there were buildings designed as promises of, and monuments to, continuity.

During the last two centuries, as urban theories and doctrines of change have become more and more vehement, the degree and efficacy of such everyday protection has correspondingly increased. Recently the insulation of the citizen has become so total that it has become suffocating. He lives alone in a serviced limbo — hence his newly-awakened, but necessarily naïve, interest in the countryside.

Читать дальше