As most critics agree, Tavares’s imaginative ventriloquism of some of the greatest modernist and postmodernist writers is a bracingly original project. And yet one might argue that the “real” Misters Valéry and Henri were an important inspiration for Tavares’s growing Neighborhood, and an inspiration, ironically enough, through their own invented characters. Both the eponymous main character of Paul Valéry’s only novel, Monsieur Teste, a hyper-self-conscious gentleman who attempts to live by the precepts of his intellect, and Henri Michaux’s Plume, star of the prose poem collection A Certain Plume , have much in common with Tavares’s elegant, seemingly befuddled, and yet oddly wise Misters. For example, in one Michaux prose poem, “A Tractable Man,” Plume wakes up to discover that the walls of his house have disappeared and, only mildly unsettled, he returns to sleep. When he awakes again, a train is bearing down on him and his wife, but again sleep beckons. Awaking once more, he discovers pieces of his wife left behind by that passing train, but again his eyelids grow heavy. The (sleepy) aplomb with which Plume faces the disasters of the dream and waking worlds reversed reminds me of “Mister Calvino’s 1st Dream,” where during the course of a thirty-story fall Mister Calvino manages to tie his shoes and knot his tie just before “he touched down on the ground, impeccable.” Mister Henri, meanwhile, displays logical leaps that Monsieur Teste might be proud of, in “The Theory,” which I quote in full.

Mister Henri said, “The telephone was invented so that people could speak to each other from far away. The telephone was invented to keep people away from each other. It’s just like airplanes. Airplanes were invented so that people could live far away from each other. If neither airplanes nor telephones existed, people would live together.

“This is just a theory, but think about it, my friends. What one needs to do is think at the precise moment in which people least expect it. That is how one surprises them.”

Those last two lines might serve as a working definition of Tavares’s teasing approach to the reader throughout his work.

Whatever his influences, Gonçalo M. Tavares has carved out an imaginative territory quite unlike that of other Portuguese writers. Yet his literary sensibility remains deeply embedded in his country’s culture, particularly the love and respect bestowed upon writers. The identity of poets and writers, contemporary as well as classic, are frequently posed as questions on TV quiz shows. Newspapers and magazines offer as loss leaders collectible coins featuring the faces of authors or limited editions of a poet’s latest work. When I lived in Lisbon the most popular television program was the reality show A Bella e o Mestre , and three of the four judges were writers. The great twentieth-century poet Fernando Pessoa has posthumously become something of a Portuguese national hero, with new edited editions of his work continually appearing, and his image is available on T-shirts, coffee cups, key chains, notebooks, bookmarks, decorative tiles, even “Do Not Disturb” signs that quote him (one hangs on my bedroom door): “Deus quer, eu durmo, a obra nasce!”—God willing, I sleep, the work is born!

Yet Pessoa is not the only Portuguese writer whose legacy is so lovingly attended. When the surrealist poet and painter Mário Cesariny died in November 2006, every Lisbon newspaper devoted their front page, and the entirety of at least their next six or seven pages, to his life and work. Similar attention observed the passing a few months later of the poet Fiama Hasse Pais Brandão. Throughout Lisbon, streets and parks are named after novelists, poets, and journalists, and statues of the most prominent writers hold central place at popular squares and thoroughfares. Even small towns display statues of local minor poets.

There is a reason for this tradition of admiration, one that has deep cultural and historical roots. A large part of the Portuguese national identity rests on that country’s unprecedented feats of exploration in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The great discoveries that created the Portuguese Empire were forged together with the birth of early modern Portuguese literature, not only in the work of Luís de Camões, an explorer himself whose major work, the epic poem The Lusiads , celebrated the explorations of Vasco da Gama, but also in the far more skeptical plays of Gil Vicente. While those globe-spanning adventures reside in the distant past, I believe that the Portuguese consider that their writers are continuing the tradition of explorers, though now of a different sort: they are patient discoverers of interior empires.

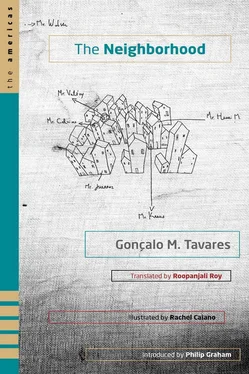

Small wonder, then, that the Portuguese have embraced the work of Gonçalo M. Tavares, which so often playfully memorializes the mental landscapes of famous writers. An early work, which was published in 2004, around the time of the first books of The Neighborhood , is Tavares’s Biblioteca . This collection of nearly three hundred short prose poems, each one about a different author, from Adolfo Bioy Casares to Zhang Kejiu, employs a tactic similar to the Mister books, by creating a space within which the imagination of the author in question can breathe. These prose poems are like little seeds, with all of the subjects of the Mister series appearing here, while others, such as Mishima, Woolf (finally, a female writer!), and Gogol, are part of the projected expansion of The Neighborhood .

Biblioteca reads as a tour through the various strands of influence that have forged Tavares’s own work, the essence of his personal library — not the one on the shelves, but the one in his head. And here, I think, is where Tavares, in his growing universe of The Neighborhood , connects most deeply with a reader. We each have our own internal library, the jostling within of the various imaginations of the writers we most care for, a library where, as we grow older and the specific details of our favorite books fade, the force of their imaginative universes remains and morphs into a quite personal neighborhood. When we visit Tavares’s neighborhood, its building blocks made of books, we are also visiting a version of ourselves.

José Saramago, who once playfully declared he’d like to deck Tavares out of jealousy, has also been quoted as saying, in a much less threatening manner, “Gonçalo M. Tavares burst onto the Portuguese literary scene armed with an utterly original imagination that broke through all the traditional imaginative boundaries. I’ve predicted that in thirty years’ time, if not before, he will win the Nobel Prize and I’m sure my prediction will come true. My only regret is that I won’t be there to give him a congratulatory hug.”

Well, who knows how to read those leaves? We do already know that Saramago won’t be there, unfortunately, if that award ceremony comes to pass. If it does, the achievement of the steady population growth of Gonçalo M. Tavares’s Neighborhood may very well be a significant factor in his ticket to Stockholm.

Philip Graham

Professor, Creative Writing

Fiction editor, Ninth Letter

University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

Author of The Moon, Come to Earth: Dispatches

from Lisbon

Friends

Mister Valéry was very short, but he used to jump a lot.

He explained: “I am just like any tall person, except for less time.”

But this constituted a problem for him.

Читать дальше