And after this somewhat enigmatic statement, Mister Valéry continued on his daily stroll, with his body bent slightly forward, his hat jammed on his head, and alone, completely alone, as always.

The Inside of Things

For several years, Mister Valéry earned a living by selling the inside of things.

Mister Valéry did not sell the object, so to speak, but only the inside of the object. The buyer would take a dish, for example, but in truth he owned only the inside of the dish.

Mister Valéry explained, “This, for example, is a dish.” And he drew

“And what I sell is the inside of the dish.” And he drew

At this point people would say, “But what you have drawn is the outside of the dish!”

“Yes,” replied Mister Valéry, “but what I sell is not what you see, it’s the inside of the dish. I know it is easier to understand what the inside is in a hollow object,” Mister Valéry used to say, “but please do make an effort.”

Problems, however, arose when the owner of the inside of something happened to meet the owner of the outside of that same object.

Heated arguments took place on such occasions.

In truth, both buyers could never be content, unless they lived in the same house. However, such coincidences do not happen very often in life. And that explains why Mister Valéry’s business never really took off the ground.

They accused him of being a swindler, but Mister Valéry was merely someone who thought a lot.

Literature and Money

Mister Valéry always carried a book covered in plastic, with a rubber band around it, under his arm.

Besides reading the book, he used it as a wallet, to keep his currency notes.

Mister Valéry explained, “I never liked separating literature from money.”

Mister Valéry therefore organized himself thus (these were his rules):

He never placed more than one note between two pages of the book.

He placed lower denomination notes in the front section of the book, and higher denomination notes in the pages at the back.

And instead of using a bookmark to mark the page where he had stopped while reading the book, he kept his coins on that page, thus, in a certain way, making the book look rather plump.

Mister Valéry always kept his identity card on the last page.

This was the drawing Mister Valéry would draw to explain his relationship with literature and money.

And each time he drew the drawing, he would repeat, “I never liked separating literature from money.”

Thus Mister Valéry’s comportment, both while reading as well as during commercial transactions, followed rigorous and immutable stages.

In the first place, he would carefully remove the book from its plastic cover.

Then, still being extremely careful, so that no coin or note would fall out, he removed the rubber band around the book.

The third step was to open the book to the page where he had stopped reading, which was easy since that was where Mister Valéry kept all his coins.

Irrespective of whether he was engaged in a commercial transaction or whether he was resuming his perusal of the book, Mister Valéry would first tip out all the coins into his hand, holding the book very carefully, so that no notes fell out. Then, if it was necessary to make a payment, Mister Valéry would look for the right notes, leafing through the book like someone who was looking for a particular phrase he had underlined.

If he was opening the book in order to read it, Mister Valéry, after tipping the coins out into his hand, would arrange them in a pile on the table in front of him, and then begin to pay attention to the text. When, in the course of his reading, Mister Valéry reached a page with a note tucked into it, he would immediately move the money a few pages forward.

In contrast, when he was about to finish a book, all the notes inside it, even the large-denomination ones, were shifted to the page behind the one he was reading, that is, the page behind the coins, which always caused him to experience a rather strange sensation.

Whoever passed by Mister Valéry and saw him seated in front of a table in a café, tightly gripping both sides of his book with both hands, was never able to figure out if Mister Valéry’s tense arms were due to avarice or a profound love for literature.

Thefts

Mister Valéry had two black bags which he never let go of whenever he was in his two-room house.

He was obsessed with the idea of thieves.

Before Mister Valéry left one room in his house in order to go to the other, he placed all the objects in the room in one of the black bags, and then went to the other half of the house with an easy mind.

When he went back to the first room, he would open the first bag, take out all the objects, and place them back where they belonged, firmly clutching, all the while, the second bag, with all the objects from the other room, in one of his hands.

Mister Valéry explained, “That is why I have so few things. It is very hard work putting them into and taking them out of the bags.”

Whenever Mister Valéry went out, he would take both bags with all the objects from both rooms, cross the street, and deposit them in the safe of the Bank.

Mister Valéry explained, “It’s only a precaution.”

And Mister Valéry really liked drawing his black bags because they were easy to draw.

The Shadow

Mister Valéry did not like his shadow; he thought it was the worst part of himself. Thus, Mister Valéry would go out only after studying the sun at length and verifying that he did not run any risk of having his shadow appear.

Mister Valéry explained, “It’s a blot that sometimes becomes visible and foretells death.”

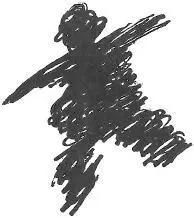

And he drew

For this reason, Mister Valéry almost always went out only at night, walking through the unlit streets with a small lantern.

When the city’s residents were sitting down to dinner and saw a small light advancing steadily, they knew that Mister Valéry was out there; and, sometimes, on account of the sympathy that this small obsession evoked, they would open their windows and greet him.

“Good evening, Mister Valéry, good evening.”

Despite Mister Valéry’s diminutive stature, people felt safer knowing that he was somewhere out there, at night, walking through the streets with a lantern.

The Phantom Stepladder

Mister Valéry believed in phantom-objects.

Читать дальше