Clint said sometimes he used to slip in the laundrymat and watch the clothes float in them glass portholes. He’d listen to the blue jean buttons and loose change clinking around. He’d watch that round and round motion and get sad, thinking about a circle that kept going and didn’t end up anywhere. Sometimes his daddy found him and bought him a Coke in a glass bottle and a pack of peanuts to pour in it. Then Clint said that old laundrymat life was finally over, at least for a while. His daddy got a job driving the garbage truck long enough to put back some money. One day he came out of the house with a paper sack in his arms. Clint’s mama was screaming and throwing his things out behind him. Clint followed his daddy in the street and asked, “Where are we going?” His daddy said, “I got us a little spot by the lake.” Clint said when they got down to the water, it was the prettiest place he ever seen. Him and his daddy was happy there from the start.

Clint spent every day he could in the lake until it got cold, trying to be a fish. He’d sink as far as he could and stay down for as long as he could hold his breath, because he knowed it was all going to end. He said it was like time stopped when he was under the water and he wanted to stretch it out. He could see his daddy getting sicker and sicker. He remembered what his mama said when his daddy left. “That’s all right. You’re just slinking off to die, like a dog does. Mark my words. It won’t be long.” Clint hated his mama having the last laugh, about as bad as he hated that his daddy was fixing to die.

But while his daddy lived, they had a nice life by the lake. Clint came and went as he pleased. He didn’t have to do homework. He failed three years in a row. Only reason he went to school any was because the truant officer threatened to put his daddy in jail. He never had to take a bath either and got dirtier and dirtier. He said them dirty smells was the ones he liked best, greasy hair and black feet bottoms and most of all fishy lake water. I thought that might have been what brung us together, the way we both loved fish. We must have seen each other’s secret scales glinting under our skins. There was something the same inside of us. Clint talking about his life always made me think about my own. I seen we could take care of each other in a way our mamas didn’t know how to.

After Clint went back with his mama he thought every day about running off. But he said there was a part of hisself that would always be afraid of her. It was like her shrill voice froze him up, especially with his daddy gone. Clint told me, “If it wasn’t for Daddy, I never would have been brave enough to get away from her in the first place.”

She made Clint go to work at the grocery store and help pay the bills. He didn’t mind about that. The store wasn’t as good as the lake, but it was still someplace to go. He said he liked the people there. He looked forward to going to work at night, but during the day at school he’d set around in class and get mad at his mama. It was like she won, and he couldn’t stand it. He’d beat up other boys the same way he wanted to beat on his mama. He was sorry after he fought them, but he said he couldn’t help it until he met me. “All that black hair of yourn looked like a big old pool of lake water,” he leaned over and whispered in my ear one day. “When I was standing behind you out yonder, I just wanted to dive right in it.” Hearing him talk that way made me feel like I was worth something.

Clint told me all them things on the bus. Then he started bringing me presents, mostly barrettes and combs. I knowed he wanted them done up in my hair. I’d fix myself in the school bathroom and take it down before I got off the bus. I figured Pauline might not like my hair done up that way, but Clint sure did. Before long, we loved each other.

JOHNNY

After my visit with Laura, I made up my mind to attend the counseling sessions, as much as I hated the pastor’s son. Seeing her took something out of me. I couldn’t stand being at the children’s home any longer. Each meal at the fellowship hall soured on my stomach and the smell of wet limestone began to hurt my head. I was too tired to climb the iron fence anymore. I knew the only way to earn my freedom was to do as I was told, so I sat with the others in a circle of folding chairs and pretended to listen. The summer before I turned fifteen, the pastor’s son decided I was ready to have foster parents again. Nora Graham took me in late August to Wanda and Bobby Lawsons’ old clapboard house outside of Millertown. They worked long hours at the gas station they owned and when they got home they went to bed. They seemed more interested in the check the government provided for my upkeep than in being my parents and I was grateful for it. At the end of five years living among so many strangers, all I wanted was to be left alone.

Like the children’s home, the Lawsons’ house was ringed in woods. It wasn’t the same wilderness I was used to, with craggy bluffs and limestone caves. These woods were flat and crowded with tall, skinny trees, the ground humped with snaking roots. I could walk for hours without the scenery changing, save a random piece of rusty junk here and there. Once I saw an old stove on its side, half buried in kudzu, and once a car bumper shaggy with honeysuckle. I traveled so far that I came out behind the high school, standing on a rise overlooking the football field. I saw how close I was to Millertown, how easy it would be to find Main Street and Odom’s Hardware. But I still didn’t know whether I wanted to forget who I was or go looking for the man I came from.

Then I met Marshall Lunsford on the first day of high school and everything changed. At lunchtime I went through the line and took my tray to the first empty seat. There was a boy sitting across from me eating a greasy square of yellow cornbread. He was gawky and long-necked with dirty fingernails and a head full of cowlicks.

“You’re lying through your teeth, Marshall,” the fat boy beside him was saying. “There ain’t even no coyotes around here.” He looked across the table at me. “You should’ve heard what all this retard said.”

“I ain’t retarded,” Marshall said. “Me and my daddy went hunting up on the mountain and I seen a coyote.”

“That ain’t all he told,” the fat boy piped up. “Why don’t you tell him the rest of it, see if he believes you any more than I do.”

Marshall’s face turned red. “It ain’t no lie. Me and Daddy got separated. Then I heard this growling noise. There was a female coyote coming out of a cave. I guess it must’ve had pups. Well, I stood right still and it kept coming at me.” Marshall was enjoying himself, getting carried away. He leaned forward. “I figured I ort not to run, cause if I fell it would’ve ripped my throat out. I stood my ground and the next thing I knowed, that coyote was jumping at me. Then I caught hold of its head and gave it a twist. That thing fell down dead with its neck broke, hit the ground like a rock.”

“You’re full of it,” the fat boy said, shaking his head.

“What mountain was it?” I asked.

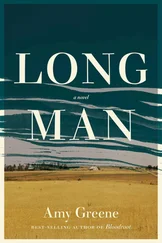

Marshall’s eyebrows shot up. He seemed startled that I had spoken to him. “Bloodroot Mountain.”

“You live on Bloodroot Mountain?”

“Down at the bottom of it,” he said, and went back to stuffing his mouth with great hunks of cornbread.

“You really believe this retard killed a coyote?” the fat boy asked smugly, as if he already knew what my answer would be.

I looked Marshall over, cold settling around my heart. “He might have.”

Marshall looked up from his tray at me with surprise and gratitude. I could tell that he thought I was an ally. It was just what I wanted him to think.

Читать дальше