“You look wonderful,” I told her. “Pink but powerful.”

Thus fortified, she turned back to our daughter, reminding her that we still hadn’t bought her anything for the upcoming school year. “Why don’t you take my credit card and go to the mall?”

“I’d rather go to prison.”

“You can’t wear the same thing every day.”

“Why not? I’m not cold. I’m not wet. I’m not naked.”

“But, Priscilla, it’s going to be in the high nineties today.”

She shushed her and pointed up at the radio. My back stiffened. My chin lifted. I turned one ear in the direction of the noise.

“But let’s not forget about the women, Mark.” A second voice had begun to speak. Calmer than her co-host, she sounded as if she were leading a guided meditation. “The women are farming organic too,” she said. “Are you out there, Ellen Mills? Are you joining us this morning on listener-supported 1640 AM in beautiful Eugene, Oregon? If so, save some of that red cabbage for me. Mark, you have to try this stuff. It melts in your mouth, people, really it does.”

“Get to know a woman like Ellen Mills, America! She’s our only hope! You think I’m kidding? Just last month in Moses Lake, Washington, a twenty-four year-old man walked down the soda aisle of an Albertson’s supermarket and shot two nuns dead.”

“Oh dear!”

“And do you know why?”

“Why’s that, Mark?”

“He got very heavy into the diet soda.”

“Oh no.”

“And he snapped. For some people it takes a lifetime of use, but for others it’s over with that first sip.”

As if on cue, Betty rose from the bottom shelf of the fridge, cracking open her second can of diet cola that day.

“Mom!” Priscilla spat grapefruit into the sink. “Didn’t you hear what they said?”

Betty shrugged, sipping from the can. “It’s not exactly peer-reviewed.” Then she turned in a slow circle, wondering, “Where did I leave my keys?”

Priscilla rinsed her mouth out at the sink, spitting loudly every few seconds.

I pointed up at the radio. “Your mother’s right. These people, they’re, you know, they’re probably broadcasting from a van somewhere out west.”

Ernest finished off The Manwich and reached for a glass of orange juice he’d dyed with a splash of red food coloring. A “Bloody Sunrise,” he called it.

“They’re probably wearing tin foil hats,” I said, “and have underlined passages of Nostradamus at the ready.” I tried a little chuckle. “Who’ll bet me? Five dollars we hear Nostradamus’s name before the top of the hour.”

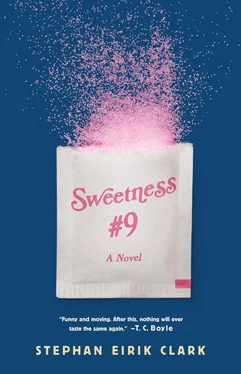

“Symptoms of Sweetness #9 poisoning include anxiety, apathy, a generalized dissatisfaction with life.” The man was rattling at his handcuffs. “Aphasias and impotence, rage disorders, dyspepsia, a forgetfulness that verges on panic. Do you want me to go on?”

Priscilla was blotting a paper towel against her tongue. “I’m gonna die!” she said.

Betty came out of the pantry, shaking her keys up over one shoulder. “Here they are!”

“Didn’t you hear him?” Priscilla said. “‘A forgetfulness that verges on panic.’”

Betty opened the fridge and crouched down before it. “I may be forgetful, dear, but I’m nowhere near panicked. Besides, if anyone knows this stuff is safe, it’s your father. He tested Sweetness #9 on rats and monkeys when he was just out of college.”

Priscilla looked at me in disbelief.

The voice of the woman on the radio dropped to a whisper. “Sweetness #9 also disrupts the menstrual cycle, ladies, so if you’re having female problems…”

“Okay, that’s enough!” I jumped to my feet and twisted the radio’s dial to off. “How come we can never listen to a little light jazz?”

“Is it safe?” Priscilla said.

I was all adrenaline and fear, a trapped animal intent on escape. Again I pointed at the radio. “They might as well be naming every ailment of the American Condition! Why not blame all these things on lack of exercise, or improved methods of detection? Social isolation,” I said. “I can go on.”

Betty rose from the fridge then, holding a small plastic container of pre-cut cantaloupe and a bag of shake-and-serve salad that came with a white plastic fork and a squeeze packet of low-fat Italian dressing that I knew must be sweetened by The Nine. Looking at her bar-coded lunch, staples she always insisted I pick up for her at the supermarket, I felt like an inflatable thing that had been popped with a pin, and could manage no more words in my defense. Were we really a country that couldn’t even cut its own cantaloupe anymore?

At the beginning of my career, when the average kitchen in this country was half its current size and used twice as much, I’d believed my work was contributing to the liberation of the American housewife — and that mine was a patriotic and essential duty, too, for once women were set free from the demands of the daily meal, they too could contribute to the nation’s economy and help lift our GDP, thereby showing to the world just how superior Capitalism was to Communism.

Even after Betty went off into the workforce and our schedules began to conflict — Betty and I with our careers and various professional organizations, Priscilla with a growing sense of volunteerism, and Ernest with the sporting life we inflicted upon him even after he’d discovered something he truly loved, a leadership position in the Young Druids Club of North and Central New Jersey — even after all of this, I didn’t feel any great reservations about the changes I was helping to bring about. By then, we had Aspirina, who provided us with healthy, home-cooked meals to fuel our many endeavors. Working in consultation with each family member, our housekeeper stashed dozens of color-coded Tupperware dishes in the stand-alone freezer in the garage, allowing us to reach for and reheat them at our own convenience. Priscilla’s had had red covers and been increasingly influenced by conscience (free-range chicken, grass-fed beef) more than good taste. Betty’s containers had been green and governed by the fear of another name; there wasn’t a diet too unethical or unscientific for her to try. Since kicking off all of her weight with the help of Jane Fonda, she’d counted points and done The Scarsdale, followed Jenny Craig, and lived for long stretches of time on little more than cabbage soup. Presently, she was refusing the potatoes, grains, and breads she’d sworn by in the eighties, and was eating a diet so heavy in protein you would’ve thought she was a bear preparing to sleep through the winter. Only Ernest had gone without. (The dietary habits of the world’s oldest men and women had influenced the contents of my containers.) He had always loved the chicken enchiladas and soft tacos and wet burritos that Aspirina had made especially for him, but at some point he had come to love their commercially made counterparts no less, perhaps even more. So enamored was he of the products of my profession that he knew gas stations according to the quality of the frozen pizzas they sold and could speak of the complexities and nuances of a two-minute hamburger as if he were a Frenchman with his nose thrust into a glass of that season’s first Bordeaux.

As Betty turned from the fridge, Priscilla pushed up on her toes to click the radio back on. The male co-host was describing The Nine’s chemical composition (9 percent methanol) and telling us that our bodies couldn’t metabolize its constituent parts (formaldehyde and formic acid).

“And to think that’s why my thighs have been growing all these years,” the woman said. “I haven’t been getting fatter — I’ve been storing Corporate America’s formaldehyde!”

Betty had gone to the counter to pack her things into an insulated lunch bag, but here she looked up at the radio. “It causes obesity? But that doesn’t make any sense. It’s a no-calorie sugar substitute.”

Читать дальше