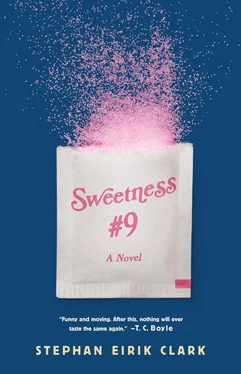

Stephan Eirik Clark

Sweetness #9

All great change in America begins at the dinner table.

— Ronald Reagan

Part One ANIMAL TESTING, Summer 1973

WHEN I SAY IT ALL began with monkeys, I don’t mean to issue another rallying cry in the ongoing Culture Wars. I only mean to say it began in the Animal Testing labs at Goldstein, Olivetti, and Dark, to which I was shown after filing my thesis on the biophysics of brie and being graduated from the food science program at Rutgers University.

Goldstein, Olivetti, and Dark. They were no less an industry giant then than they are now, with five thousand employees worldwide and production facilities on every continent but one. I certainly felt a good thrill in joining their number. As I first pulled up to the gate of their ocean-side complex in Jupiter Park, I believed myself just as important as one of the policy wonks inside the Beltway or an engineer bent over a slide-rule at NASA. It was the summer of 1973 and I too was doing my part to win the Cold War, for if anything other than an ICBM could clear the Berlin Wall, it was the taste of a smuggled Ho Ho or Ding Dong — flavors that suggested a life freer and more limitless than any possible under the grey yoke of Communism.

After parking, I was met in the lobby by one of the men who’d interviewed me, a middle manager with the company’s Laboratory for the Development of Substitute Materials. A short, round fellow with a tonsure of dirt-brown hair, he was constantly hoisting his belt or running a finger around inside his tight collar. I’d forgotten his name (it was either John Rogers or Roger Johns; he was one of these blue-blood types), so for fear of making a mistake I called him “sir.”

“Just this way now, Leveraux.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Here we are.”

He moved across the red carpet into a bay of wood-paneled lockers, found the one he was looking for, then fished a key out of his pants pocket and gave me a wink.

“Well?” he said. “Shall we? Hmm? Hmm?”

At the age of twenty-four, my most natural expression was a kind of smile-in-waiting, the face of someone politely anticipating a punchline to even the most poorly told joke.

“Yes,” the middle manager said, as he popped open the locker and reached inside for a white lab coat that was hanging motionless on a pink plastic hanger. “Give ’er a whirl.”

I switched out of the blue blazer I’d worn from home, then stepped up to the small panel mirror attached to the inside of the locker door. My name had been stitched in blue thread over the breast pocket: David Leveraux, Flavorist-in-Training. I went to trace my finger across it, but before I could, John Rogers slapped me hard on the shoulder, knocking my hand off course.

“A million dollars, Leveraux! A million dollars!”

He led me out of the dressing room and down a long checkerboard hallway to a sign jutting out over a far door: ANIMAL TESTING, it read in red-on-white letters. The middle manager ushered me into the lab with a sweeping gesture of one hand, telling me as I passed before him that I’d be working with rats and monkeys.

I turned beaming to him after I’d stepped inside, my eyes as shiny as the Vitalis I combed through my hair each morning. “Rats and monkeys?” It was my introduction to the American economy. “Splendid,” I said. “Splendid.”

And how couldn’t I be so thrilled? It was a wonderful time to embark upon a career in the flavor sciences — a Golden Age, I can’t help but think now. Just consider: in the nineteenth century, the industry existed solely for the benefit of the baker, confectioner, and soda maker, but following the end of the Second World War, the profession experienced a great westward expansion as a result of the TV dinner — a Louisiana Purchase that was drawn in the shape of a four-compartment aluminum tray. This was added to in short time by the launch of the first domestic microwave, a Sputnik-like event that caused young men such as myself to heed the call of the nation’s top food science programs. I was now on the other side of my Master of Science degree and being asked to start in Animal Testing, but this was in no way unexpected. Animal Testing at Goldstein, Olivetti, and Dark was like the mail-room at the old William Morris Agency; even those recruited out of the Ivy League started here.

“Well?” With another sweep of his hand, Roger Johns revealed the world my dedicated scholarship had won. “What do you think? Hmm?”

Two island work stations rose from the center of the room, their black counter-tops holding microscopes and Bunsen burners and stainless steel sinks. To our right was a wooden maze on a thigh-high table. To the rear, two doors, one marked PRIMATES, the other RODENTS. The door to the primate room stood ajar, allowing the screeches of a more primal tongue to reach my ears. Hearing this, I pushed at the bridge of my glasses and squinted behind their thick black frames. I could make out only the first of the floor-to-ceiling cages inside, but I saw the beasts so clearly in my mind: rattling their doors, jumping up and down, exposing the pinks of their gums.

“Chimpanzees, are they?”

“Mmm.”

“Lovely,” I said, though in truth that shrill glottal sound, the screaming of the jungle… Some men dread clowns or midgets, others a ventriloquist and his dummy. For me, it has always been monkeys, monkeys by any name. I feel their presence like a cold finger pressed into the base of the spine, and so for a moment, just an involuntary flash, I wished I had joined a smaller outfit, one that would’ve dispensed with the cage cleaning and other rites of passage and let me begin as so many other would-be flavorists did, by mixing chemical compounds in a 250 cc beaker.

But then I had prepared myself for this and was ready with all the necessary rejoinders. At the end of six months, certainly no more than a year, I would be transferred into the Flavorings Division on the third floor, where I’d be assigned a mentor in the specialty of my choosing, most likely Breakfast Cereals. And here I would be able to dream bigger, because Goldstein, Olivetti, and Dark not only possessed state-of-the-art laboratories; they offered access to an unrivaled Research and Development Department. Just the previous summer, the company had floated an air balloon across a stretch of dense and virginal jungle in Papua, New Guinea. The team had drifted over the treetops, hovering in place and dropping a long vacuum-driven tube each time it wanted to capture a specimen from beneath the lush green canopy below. More than two hundred fruits, flowers, barks, pods, and mushrooms had been collected, along with at least five new plant specimens and one frog whose skin was reportedly covered by a sweet-tasting mucus.

I challenge you to find the young man schooled on Guenther and Bedoukian who could resist such talk during his interview. After all, though Gas Chromatographs and Mass Spectrometers had become commonplace in the last decade, these instruments were only as valuable as the information you fed into them; and by this stage of our country’s culinary development, no one company alone had tagged and quantified more than fifteen hundred volatile flavor chemicals. That meant if you injected a sample into the GCMS — a pot roast, let us say — the computers would only be able to identify the most obvious peaks and valleys of its flavor profile. It was no more helpful than a seismograph that could record an earthquake only if it shook the decorative plates off your shelves, because to produce a truly remarkable flavor, one that left even its creator confused as to its origins, you had to know what a sample’s subtlest notes were comprised of, and this in many ways was a godly task. Consider the humble pot roast. It is a sublime creation rising up from more than six hundred different flavor molecules — and that’s before it’s served alongside a dollop of garlic mashed potatoes and a pile of pork-fat green beans. So, no, I didn’t come to Goldstein, Olivetti, and Dark because they had an impressive fleet of technological hardware; I came because they knew what their machines were saying. With such vast resources and so many privately held compounds, Goldstein, Olivetti, and Dark boasted a veritable Book of Life. I wanted to lick their frog. Call it youthful exuberance if you must, but I wanted to taste the sweetness that had been sequestered for so long in nature and now called Jupiter Park home.

Читать дальше