Hold put the headlamp on and walked down the field and stopped, sensing the rabbits scutter and shift ahead of him, seeing him first in the moonlight. He flicked on the headlamp and scanned the space in front in a slow, sweeping arc and the rabbits looked back at him, their misunderstanding eyeshine reflected back in pinkish discs.

The bullet spat through the silencer and in the scope he saw the rabbit turn over and shake and die, its mouth still working for a second, then its back leg kicking automatically out in the final statement of its instinct like some unwound spring, and he lowered the scope and switched off the beam so as not to see the final parts of its life shudder out of it. He went over the tide times in his mind and worked out how long he had to work his way down to the nets on the beach.

You could leave the nets there and let them be exposed but there was always the chance that something would get into them if you had any fish. There wouldn’t be birds in the night, not before dawn, but a fox would go down there, and even a polecat, or otter, which they said were getting stronger again and would follow the freshwater streams down to the shore and hunt there. On the big tides like this, the sea went out quickly for the first important distance and this was where his nets were set, at the edge of the high water mark, so he calculated they would be lying open three hours before the low tide.

Early in the year, sometimes he had risked leaving the nets down for two tides, leaving them in the midnight ebbs, and the fish that had lain in the net from the first tide would be clean inside, with their vents dug out where the minute crabs had gone into them and eaten the guts of them out. Birds generally went for the heads and he hadn’t had a bird caught in the net ever and he was thankful for that because it was a small dread to him.

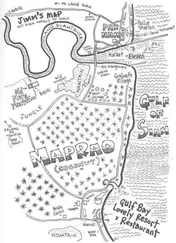

He could see the scallopers out on the five-mile line and he thought of the great difference between pulling a trigger and pulling a dredger, and of the personal deliberateness in one and the indiscrimination of the other.

They opened up the beds, and the scallop boats on the horizon had arrived strangely one night as a line of lights almost like a village strung out along the furthest line of sight. At Christmas they were joined by further boats and the sea at night looked decorated. They had worked the beds for months, dredging with heavy nets loaded down with iron frames.

A month or so ago, a man went overboard. After searching for hours, all the boats came in from respect, and Hold had some sense that something in that man must have wanted to have gone, because, Hold thought, it must be difficult to fall into the sea from a big boat.

He thought of the dredgers and he thought of their netted iron buckets smashing blindly over the seabed and how the men on the boats did not have to see the making of the desert they would bring about; and he thought: there are forces that work that way in everything that happens.

And perhaps in that moonlight he thought too much. And he thought whether it was better to make choices, and to take directions and risk a net being there; or whether it was best to stay bedded somewhere, and risk some great thing being dragged through you. And he thought how Danny had died, and how that was like some great thing dragged through him, and how it had left the bed he’d made smashed and damaged and dis-anchored. And how, for a very long time afterwards, the people who were close to him couldn’t see where they were in the sand.

He collected the three rabbits he had shot and laid them out side by side on the turf and put the bag onto the grass and went down on his haunches using the rifle for balance. He took out the gun bag and checked the rifle over once more and then put it away and lay the gun bag down.

It was important to paunch the rabbits immediately so the meat would not change, and one by one he took the rabbits and cleaned them, cutting the glistening ropes of gut and the stomachs out to lie on the ground as some bonanza of his surgery. It was an unusual thing to use the knife of his friend which was usually for fish but he had found a way with it, and he used it out of sentiment and a sense from somewhere that a man did not need more than one knife.

For a moment, there was moonlight, the inside of a shell, some shard caught in the dark mass of that eye, a part moon reflected as he held the rabbit down.

He knelt in the cropped turf and dry sea thrift and finished the last rabbit and, before cutting them, with his thumb he had peed the rabbits by forcing out the last urine from their bladder.

There was a constancy without rhythm to the sea below, swelling and crushing with almost a machinelike quality with that same sense it had contained within itself for days. Like some broken metronome for the earth. Just from the sound he knew how the breakers would look, moving up from the fluid sea as if great boastful shoulders were beneath them, then crushing down. It was like a wrestler throwing someone. It was as if Hold acknowledged those thuds somewhere inside him, like acknowledging a stronger man.

He could see the clouds scud slightly and lift in the sky and start to move, and knew they would come over in a little while and wondered if, after he’d worked the nets, it would be darker and easier to shoot on the cliffs afterwards. But there was something inside him this night that did not feel like shooting, and it was part of the same thing that had stopped him waking the boy.

He wiped the oily blood and fluids off his hands in the short dew-covered grass and knelt on the bag for a while looking at the rabbits. The guts were warm, and steamed. He was suddenly and briefly tired. And in that moonlight he felt it would be nice to build a house around himself and sleep. He pushed from his mind the thought that it would have been nice to walk into that room and lie down with her and begin something. He hoped it would stay brotherly. He hoped they could keep it like that.

He got up and picked up the rabbits and had the emptiness for them that he had momentarily with the wild things he killed, because of the perfection they had and which tame things could never possess. The white in their fur showed up in the moon and they were the color of fish for a moment, glistening silver. Then they seemed to dull, to become dark patches in his hands.

He put the rabbits in the bag and clipped it up and took out the headlamp and shone it just from his hands and went on down toward the cliff path to the beach. Here and there on the coast that swept the bay, towns showed like the last glowing ashes of settling fireplaces. The rest of the coast was dark, permanent, impassive to the pleading sea, which beat in with a steady, repeated argument against the wreck of the shore.

He could imagine, years ago, the sea, its temper lost in storm and the dark chaos of that bay. And he saw in his mind the huge fires lit on the headlands, the lost ship come to those false beacons and dashed in those waves against the coast, its goods torn out and strewn upon the shore. And he reflected how, for this to happen, there must have been whole villages treacherous for this collection, who were not pirates in their minds, but who were like fishermen or farmers in their industry. He thought of the boy and of what he had said and of the possibility that there was treasure on the beach from this great slaughter, and as he passed, in a field he saw a herd of curlew over the ground, and they were ghostly and strange in that light.

He cut down to the beach in that dark tunnel of light, with the scree of rock ancient-formed, split and busted down the edge of the path. The iron rust showed in the rock and the smooth shale bedewed reflected and he felt for once that it was he the strange thing here. How the curlews had undone their compactness at him, and lost their peace as if he was not something fearful, but to them impossible.

Читать дальше