“We want more now,” said Grzegorz. “We’re not so simple. We can’t be happy living the old way any more. It is better to be here. Poland can rot.”

On the stove, the tripe boiled, and the stench went through the house.

He watched her cook. She had the apron on and doubled at the waist with the cord around it and her collar stayed off her shoulders and he saw the surprise freckles there, starting just on her shoulders. He stopped himself. He had fantasized about her a lot when Danny was alive but after he died had stopped himself, refused to let himself, as if it was some kind of bigger betrayal.

He was drinking one of the beers she always kept in the fridge for him and could hear in the next room Jake going round with the metal detector finding the metal things he had hidden about.

He watched Cara put the fillets into the butter in the pan and they arched slightly as the skin burned, and relaxed again. She levered them over and he looked at the beautiful netted skin of the fish, emphasized in its burning.

She stooped down and opened the oven and flicked her hair over her ear and with the oven gloves shook up the tray of oven chips and turned the tray of the loose chips round and slid it back in and shut the oven again. When she turned the fish over once more the meat was bright white.

Hold went through and helped Jake clear up the metal things all around and ready the table and she brought the plates through with the fish on and put the chips and the peas on the table. Looking at the fish, Hold had this bizarre thing that it was some white affinity that drew the fish to the moon. A sense of light.

The metal detector was in the corner and needed to be cleaned up after all the time in the shed and Hold decided he would take it and clean it.

He remembered the time Danny had hidden things about the garden for the boy, all sorts of metal objects, planting them under stones, burying them at the foot of the hedgerow. The way Danny could bring a sense of adventure into something.

The boy was younger then and every time he found something he came running to them. The find of the day had been the brooch. It was a beautiful, intricate, and damaged thing. The boy gave it to his mum.

“That’s pretty cool,” Hold had said.

“I didn’t put that there,” said Danny secretively. He had this massive, victorious wide grin.

The boy noticed Hold looking at the instrument.

“We could go treasure hunting,” said the boy, and Hold looked thoughtfully at him.

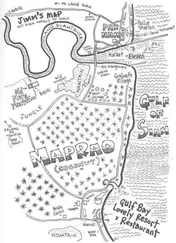

“Maybe there’s treasure on the beach.”

“Maybe there is,” said Hold. “Maybe there’s ambergris.”

The word had this kind of magic sense to it.

“What’s ambergris?” asked the boy.

Jake was picking at the chips with his hands and his mother gave him a look that stopped him.

“Ambergris?” said Hold. The boy was looking at him. He remembered Danny’s newspaper cutting, the way he had waved it with this intent belief they could find some, that it would fall to them. More, that he lived always with this chorus behind him, “What if?” always, “What if?”

“It’s whale sick,” said Hold. The boy eew-ed and laughed and did not believe him and thought he was starting one of those games grown-ups do.

“It’s whale sick and it smells of cow poo. Cow poo and perfume. Like a farm girl on a night out.” The boy was delighted.

Cara was trying to be stern but was smiling and warm at seeing the boy laugh. “Men bring an irreverence,” she thought. “It’s good to have that.” She looked at Hold ladling mayonnaise onto his plate and missed the capableness and the solidity that can be in a man’s hands.

“It’s something very rare,” said Hold, getting serious. “It’s grayish, and it stinks, and a piece the size of your plate is worth more than a new car.”

The boy’s eyes went cartoon wide. “No way,” he said.

“Look it up,” Holden said. “Maybe there’s some on the beach.” He thought of Danny’s chorus: never rule out maybe. What if? What if, really? What would he do for the chance to be able to lift all this, lift her and the boy off the tracks they were stuck on?

Cara looked at him. Sometimes she felt as if she had one-half of a man and under her clothes she could feel her body going to waste. It was he who had drawn the line. She would never hold it against him if he loved her. It was his standing off that was difficult to take.

After supper he said, “I could take him with me tonight,” and she had said, “No.” The boy was washing up and the industrious clattering came from the kitchen. Hold was toying with the salt grinder, making rings of salt on the tablecloth and pushing them into shapes with his fingers.

“He’s old enough now,” Hold said. He put the salt grinder down. “He wouldn’t shoot. He’d just walk with me. It might even put him off, seeing it. It does some people. He’s not going to let go of it otherwise.”

Cara looked at him. “It’s a school night.”

“Most of the kids will be up on their computers.”

“Not mine.” She was quiet.

“He won’t let it go, you know.”

She could feel very much that it was Hold who wanted the boy to go with him, and she waited for a long time. She felt sometimes that she should try to make the decisions Danny would have made, and not just her own. To be fairer to the boy. And she knew that she was out of her depth trying to bring up a boy and give him the leeway he would require in all the things he would want. She had a great urge to hold Danny at the thought of the boy’s growing up, and in a split second she saw his broadening, and the ropes and sinews come into his arms and legs and the coming angularity of him. “I need help with all this,” she felt. “It’s too much, all these decisions on my own.”

“How long will you be out?” she asked him.

“I could go out earlier, for an hour or two with him, and bring him back. There won’t be much anyway. I could drive down for the nets after.”

“And he won’t shoot?”

“He’ll just walk with me, and see it.” He played with the sore atop his thumb, looking down to see if he could tell what was under it.

Cara stood up and called the boy and he came through. “Sit down,” she said.

He was worried underneath being told to sit down. This is how it had come. There was always that doubt after that, his emotions all curled up like a cat, waiting to react to the huge, incomprehensible news. He knew it was stupid to feel it, but he couldn’t help it coming. Hold knew it, recognized it.

She told him that if he went to bed now, and got some sleep, he could go shooting tonight. Just for a few hours. Then she went out and finished the clearing up.

Danny had died without any cover. In this, there was a crippling lack of responsibility and Hold had had a great anger at his friend, and Cara had understood in those brief angry, bereft moments when he could not help her seeing that it had always been that way, and that it was he who had always exercised the practicalities, the safeties for what they did. The pot of water when they lit fires, the flares for the boat, calling the coastguard in advance when they went out on the boat for the night. Danny had never considered that things could go wrong, turn for the worst. Or if he had, he buried his head from them. It was what was engaging about him, but it worked only with the balancing responsibility Hold took.

Hold had sold the boat, and she had seen the great wrench of that as if someone had lifted a part of him away. She knew it was their dream between them, a few years on to work the boat and live by fishing and she could never erase the way his face looked when it went. The humble money from that had got her through the immediate costs and with her work she could just clear the mortgage. But there was nothing over. There was enough value in the old house to set them up, but she couldn’t consider that with the way Danny had been about it, with the way Hold had taken on the responsibility of it. Sometimes she saw it as this great weight that was just dragging them all down, keeping Hold in Danny’s shadow, a locked up store of money, a constant reminder of the past she wished inside she could just break away from, a millstone dragging them always into the great sea of his absence.

Читать дальше