She wanted to be let go. She could not bear the not being there of him and was confused by the emotions that were growing in her that seemed a betrayal of this great feeling.

“It’s just not possible,” the bank had said, and she had felt this internal, secret relief, that the house would go. She understood the responsibility Hold felt, understood how it felt for someone to invest their dreams in you the way Danny did. How that made you feel valuable and needed in a way that was difficult to get free from. But Hold too was a confusion to her now, a weight on her moving on. She did not know whether it was love because that thing seemed too fragile for her now but she had fallen in great care with him. It was just another fact. Another little awareness that made itself known to her, awareness which made her desperate, so she could feel small hatreds of herself growing inside, things she tried to accept or cocoon so they did not seep through her and bitter everything.

She felt, despite this great want to be around him, that it was unfair of him to be there. Sometimes she wanted to orchestrate something that would finalize it, that he could not forgive himself for. She thought of his hands on her, how her body missed touch.

Hold me, or let me go, let us go. It’s stifling you bringing him back into our life every time.

Hold came back about eleven and took the key from the nail in the porch and let himself in and put the stuff he had got together for the boy on the floor and went through to the kitchen and turned on the kettle to fill up the flasks.

She said she’d be in bed. “You wake him. Make it a man thing,” she said. “Just bring him back.” That sentence was so loaded that it went right through Holden when she said it. There was nothing strong enough he could say to it.

He put boiled water in the flasks to warm them and went to the boy’s room. Jake was sleeping. He’d got his penknife and a first aid kit out by his bed and had pulled green and camouflage clothes out from his drawers.

Hold looked down at the boy and shook him gently and said his name. He felt a strange sense of fathership, beyond his own flesh and blood. The boy looked perturbed in his sleep. Because you couldn’t see the old-looking eyes the boy had, from what he’d been through, he looked much younger sleeping. The boy had her eyes, and without them Hold could see Danny very clearly in the boy.

He shook Jake again but he didn’t wake. It was as if he was concentrating on sleep. And seeing him sleeping that way, Hold suddenly had no desire to wake him. As if he acknowledged that the boy wasn’t ready for this yet. That things should wait.

He took the piece of shale he’d taken from the beach and put it down on the boy’s cabinet. It was rhomboid, smoothed at the corners, and the three clear crystals of fool’s gold lay in a line across it, like three small dice partway through a roll.

He knew the boy was too old for it now, and would know it was worthless. But maybe he would play along. It’s what we feel something is that makes it important. In a fire, someone might grab the most worthless thing, a smooth pebble, a seashell, a dried old rose if their lover had given it to them. If they still had the energy to believe. It’s what a thing is capable of being that matters.

He looked at the boy for an odd while, then went out of the room.

He left the house and put the key through the door and got in the van. “I should have gone to her and told her that the boy wasn’t coming out with me,” he said inside himself. “She’ll work it out.” There was no way he could have gone into that room, and sometimes he knew that it was part cowardice at the responsibility he would have to take on then. It might be different if he had something that she could make a choice for. If the house was done. “I could never walk into that thing Danny has put around them, this bungalow, his place,” he thought. He could not imagine himself existing in his friend’s space, not like that.

She heard him go and knew he had not taken the boy. And she had a strong image of him then, leaning over and helping her pull in the line, and not taking the rod off her. And then she felt this great goddamned confusion over him.

He parked up the van and switched off the lights and the lights seemed to take a brief moment to go out. He knew she was right that the boy was too young to be with him for this but he also knew it was the sometimes female thing of not wanting your child to play with guns. Not from a sense of pacifism, but for the sense of responsibility it involved, and the growing up it represented. “I should take the boy out in the day and shoot some clays, show him the danger of this thing first,” he thought. There was a relief that the boy was not with him and he would not have to explain everything he did, but there was also the sense of responsibility to him; and there had come a strange sense in him, stronger as he had grown older, that the things he knew should be passed on, the sense that otherwise there was no point in things, and part of his encouragement of the boy was to give himself a chance of this.

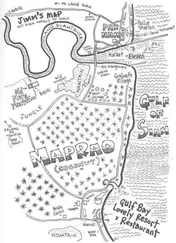

He poured a coffee out of the flask and set the cup down on the dashboard and watched the heat steam up the windshield by the cup. Below was the crush and swell of the tide going out and he could sense it in the rich and fertile moonlight. There was really a sense of being on the edge here.

Further north, the bay curved round and you could see the lights of towns, but before him was the sea with just the few lights of the scallop boats out. It gave the sense of being at the edge of an element. It was like a limit, that water, and Hold felt it would be impossible for him to move away from it. It was as if he needed the sense of this limit somehow, the great, wide, humbling space of it. “If she moves away, I don’t think I’ll be able to follow,” he thought.

He got out of the van and shook out the coffee cup and screwed it back onto the flask and put it in the driver’s doorwell and the van was very white in the moonlight. He looked up at the moon for a while, more because it was impossible not to look up at it, somehow. “Don’t think about all the other stuff now,” he said. “Put it away. It’s what you do this for.”

He opened the back and took out the gun from its case and checked it over with his careful, rhythmic habit. He tapped the light in the van back as it went out briefly and it came back on with a small buzz and he looked at the bright moon again and knew it would mean the rabbits would see him. Then he put the gun back in the case and checked that the silencer was with him and put the loose bullets in his left coat pocket and picked up the game bag with a small jerk to hear that the knife and the scales were in it amongst the plastic bags he kept for the fish.

He went round to shut the driver’s door and flicked down the sun visor and checked that in the pocket band was the five-pound note he was paid to keep the vermin down each year and that he kept from superstition — though he’d say he wasn’t a superstitious man.

In this ritual, he could feel this first slight thing come up in him and some tone in his blood and he kept it down with this patient procedure. It was a thing peculiar only to the gun and having the gun near him and he associated it in his mind with the flavor the smell of the rifle made in his mouth. There was the metal smell of the barrel and the gun oil and casings and the brief taste of foil in his mouth so even the iron and oil of the van seemed amplified, and in this Pavlovian thing he felt his nostrils flare slightly and the oxygen feel better and more useful in his head. For him, there was a very right thing in all this and something very old. It was this rightness of it, not any love of killing or feel of sport, that was his reason for doing it, and in the focus of doing it he felt his other worries begin to leave him.

Читать дальше