He shut the man’s eyes and picked up the phone and tried to switch it on but it just flashed briefly, bleeped, and went out. Then he collapsed on the reef of sand.

The headlamp was dimming and going out. He switched it off for a while and just sat there looking at the shape of the boat and the dead man in the moonlight.

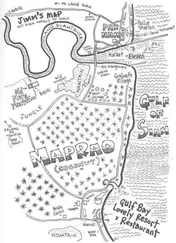

He got up and tried to walk a little of the stiff coldness out and went back to the boat. The grit and broken shells and sand that had been washed into his shoes grazed him, but it was pointless to try and do anything about that now. He knew he was hurt. It’s amazing what you can’t feel in the sea. The lume of the dawn was building and the bay was filled with this strange ancient light and he could hear turning in the energy of the tide.

He checked the man over again, went through the pockets, and lifted him to see if there were any other parts to his fairy tale in the boat, and then he took another look at the Slavic face. The wind was starting to lick up with the tide change and he bit with cold and was suddenly very hungry. He thought for a moment about taking the man’s jacket that was drier than his. Somehow in his coldness and hunger was a sense of his own reality. He clung on to that.

Gulls were coming off the cliffs and circling and began to call and other birds were beckoning in the new light. He was shaking his hands to get them warm. “What if someone was here to meet him,” Hold thought. Suddenly it was to him as if the light was some enemy, some thing that would see him. He thought back to the stones falling on the cliff earlier. “I cannot have been seen,” he said. “There was no one.” Then he saw the packages.

There were three of them, carefully wrapped, bound up in parcel tape, all about the size of a fist. He picked them up. Something inside him knew already they were packages of some dangerous, exploiting thing, which he felt a sick fear of in his gut. It was like they could speak.

He dragged the boat a little farther onto the reef and went back to the game bag and took out the knife. Then he cut a thin split in one of the parcels with the knowledge of what was in them already in him. A small, sticky spill of white powder sat up out of the split. It smelt strange on the knife. He had no idea what it was. But he knew it was drugs, and it looked raw and unprocessed and he wouldn’t be able to tell you what part of his knowledge told him this.

He looked at the parcel in his hand and thought of the worth of it and of the house and of Danny and the dead Slav and of a risk that would surely only have been taken for great wealth.

“Now what?” he said. And then he sat on the rock with the parcels in his hand, the light coming.

He’d had this image of Cara with her neck in a net, tiring herself to a beaten point of exhaustion. Of his mother. Take it, he had thought. Take this now, and try to change things, or you will have to stand by and watch it all again.

“I couldn’t have been seen,” he thought. “No one could have seen this.”

He could not take everything. He had not intended to bring the net in and had no bag for it. There were the big fish and the rabbits. The rifle had to come. He was like a point of concentration now, with the mechanism from childhood fully kicked in.

As soon as he saw them, he knew he would take the packages. He had thought briefly about taking the boat, of checking the engine for serial numbers, of weighting the man and throwing him in the water and had known this was madness. He knew he must have no connection with the packages, and he must disappear off the beach.

He went back to the net and started to take the other fish out with his numb hands, trying to slow himself in this process, and the light was growing bit by bit, even giving some luminosity to the strands of nylon as if it was becoming animate. He got the knife and cut out the fish and dumped it on the rocks and cut out the other fish and there was something almost religious about cutting the net, like he had broken some sanctity and that he had cut much more than the net in doing this thing. He went to the tangled crab and cut it free and cut and pulled away the threads amongst it and put it down on the rock so as not to hurt even this thing he had no like of. And he moved efficiently in this place of decision he had built for himself and pulled up the anchoring rope of the net from the bowl of rocks he had it in, ignoring the criminality of having cut the net.

He threw the fish down the beach and got the large plastic sack he carried for them and arm over arm piled the yards of net into it, tearing automatically at the large straps of seaweed that were amongst it. He thought about putting the net in the boat and of keeping the fish but he knew that should not be done; and he thought too about taking the fish and leaving the net lifted, and of bringing round the fishing boat and sculling out to collect it so much was his reluctance to leave the fish and to kill for no purpose. At least the gulls will have them, he thought. The bay was filling with light now and it was the point of most coldness.

He worked his hands trying to warm them and sucked at his fingers to bring the blood back to them and tasted the fish and salt water on them and the iodine tang of the weed. He put on the headlamp and took the rabbits from the bag and the nylon line and blunt needle for stitching the net and he cut out the liver and kidneys and hearts he had left in the rabbits and threw them too on the beach and washed his hands in a pool and watched the dark strings of blood come off him. As cold as he was, the water felt warm on his hands.

He took the packages one by one and set them inside the rabbits and one by one stitched up the cavities, forcing the needle though the taut hide with a pebble and the rabbits grew in weight and seemed to reconstitute their missing shape like they underwent some backwards act of resurrection.

He had sat wondering what to do and everything had happened unconsciously, as if the decisions were being made at some distance from him, and he had none of the usual discussion in his mind about what choices to make. It was as if he already knew. He had sat and stared at the boat and at the heap of man and down at his fish and had taken out the fish scales and weighed the packages one by one, hanging them by their loops of tape. And he knew that for a man to take a boat, to take this weight of things somewhere, there had to be much value in those things and he had sat for a while with his head in his hands.

He looked once more at his scattered bounty of fish and took his knife and went to the boat and took the spare fuel and refilled the tank and pumped the fuel through to the motor. Then he dragged the man into the back of the boat. He took the bow of the boat by the cord and heaved it round until it met the water and walked in with it, feeling the cold water come into him again and the man bounce in the bed of the boat and he let it ride over the waves and went with it into the deeper water.

He dropped the motor and pulled out the weed that had dragged in the propeller and took the gunwale cord and cut it with the knife, going backwards with the boat each time a wave came to it. Then he wrapped the cord over and over round the prop shaft and fed an end of it through the rings as if it might have snapped and gone itself around the engine. And as strongly as he could in the water he stayed the motor so it could not turn and pushed the boat back out into the deeper water.

He checked the prime on the motor once more and moved the choke and pressed the automatic starter and swore silently at the motor when it did not start. And then he cut off the toggle and took out the drawstring from the man’s hood and unscrewed the cap of the flywheel as the boat kept going back at the beach and he kept walking it forward. He had cut his hand somehow and it was bleeding heavily onto the wheel and he wrapped the drawstring round the wheel and tugged and sent it round and the engine spat and fired and he leveled the choke and felt the blood go down his hand. And then he dropped a gear and coughed at the spume of fuel that caught him and he let the boat go.

Читать дальше