We came on Thursday night with police personnel. All indications were that we would find something. It’s an unpleasant place still during the day, very dangerous, and it was impossible to continue after dark. So we returned with eighteen men and we worked at a depth of ten meters with tripod and rigs making it easier to extract the body. […] It’s not the first time we’ve done this. […] They [volunteer firemen Javier Bergamasco and “Melli” Maciel] had to do the hardest part, but it was a team effort.

Declarations of the head of the Volunteer Firemen Corps of El Trébol, Raúl Dominio, to El Trébol Digital , June 20, 2008

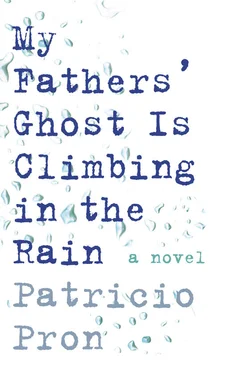

Even before the results of the autopsy on the cadaver were made public, the accumulated facts — particularly the scar mentioned in the conversation between the chief of the Eighteenth Regional Police Unit and an anonymous journalist — and an explicit desire for the missing man to be found (dead or alive, really) seemed to have led to the immediate unspoken conclusion that the cadaver was Burdisso; in fact, the following article collected by my father, an article from the twenty-first, stated outright that “the body of Alberto Burdisso will arrive in the city at approximately one thirty” and gave the name of the funeral home where the body would be laid out, the prayers said at the parish of Saint Lawrence the Martyr — the church in the background of the photograph of the demonstration four days earlier — and a funeral procession through streets with names like San Lorenzo, Entre Ríos, Candiotti and Córdoba. However, the identity of the body found in the well should not be accepted by the reader before asking why someone would want to murder a Faulknerian idiot, an adult with the mind of a child, someone who didn’t drink, didn’t gamble and had no money, someone who had to work every day to survive, doing the most menial of tasks like cleaning a swimming pool or repairing a roof. That question, which ran through the next few articles in my father’s file, is perhaps a public one. A private question — so intimate that I could ask it only of myself, and at that point I didn’t know the answer — was why my father had taken such an interest in the disappearance of someone he may not have even known, one of those faces seen in passing, associated with a name or two but of no great significance, part of the landscape, like a mountain or a river. So it was actually a double mystery: not only the particular circumstances of Burdisso’s death but also the motives that led my father to search for him, as if that search would solve a greater mystery more deeply obscured by reality.

More photographs: a white car stopped in front of a crowd, mostly of children, who were applauding at the doors of a building with a sign that read “Club Atlético Trebolense M. S. y B.”; I didn’t know what the initials meant, but the figure on the sign — a disproportionately muscular man, kneeling, holding up a C.A.T. emblem — was familiar; bunches of flowers emerged from the car’s windows and seemed about to fall onto the asphalt. The next photograph showed the same scene from another angle, the photographer situated amid the mourners; his location allowed the viewer to see spectators gathered on the facing sidewalk. There were more photographs, taken in the same moment but from different angles; what most caught my eye was the contrast between the naked colossus who presided over the sign with the initials and the coats worn by the spectators. Then there were two images of an old man who stood speaking beside the car; the old man was bald, he wore glasses and a dark coat; one of the bunches of flowers coming out of the car’s window had some sort of sash with a phrase, of which only the word executive could be read. The old man’s face was familiar to me, and I wondered if he might be that dentist who had taken a fish bone out of my throat when I was a boy, a dentist whose hands shook and consequently instilled more fear in me as they handled the forceps than the fish bone itself had. Then there was a photograph that was easier for me to identify, even though the identification came quite fast and seemed to gush out, as if my memory, instead of evoking the recollection, regurgitated it. It was the entrance to the local cemetery and there were several dozen people forming a corridor in front of the car with the flowers; in the background of the image was a palm tree that seemed to shiver from the cold. In the next photograph, the crowd is seen from another angle showing a row of trees and a stretch of flat, empty land. Then there are two trite funeral photographs: one of some people walking with floral wreaths through the main entrance to the cemetery and toward the spot where the photographer must have stood, the figures breaking up into fragments if you look quickly — a mustached face, a hedge, two ties, a jacket, the surprised face of a child, a sweater over sweatpants, someone looking back; and one of four people holding up the coffin beside a niche dug into the wall — one man facing away and another man looking directly at the photographer with a slight expression of reproach. Then there was an image of a plaque that read: “R.I.P. Dora R. de Burdisso  8.21.1956 [or it could be 1958, the photograph wasn’t in sharp focus] / Your husband and children with love”; it was probably the plaque that covered the niche before the coffin was deposited, probably referring to the dead man’s grandmother or mother — but then, where is his father buried? — so perhaps it was a family crypt.

8.21.1956 [or it could be 1958, the photograph wasn’t in sharp focus] / Your husband and children with love”; it was probably the plaque that covered the niche before the coffin was deposited, probably referring to the dead man’s grandmother or mother — but then, where is his father buried? — so perhaps it was a family crypt.

Then there was one last photograph of the event, and when I saw it I was surprised and confused, as if I had just seen a dead man approaching along a path with the infernal red setting sun silhouetted behind his back. It was my father just as I would see him in the hospital, in his final years: bald with a white beard on his thin face, very similar to his own father as I remembered him, with large rimless glasses, the glasses of a policeman or a mafioso, with his hands in the pockets of a white coat, talking, his throat wrapped with a plaid scarf that I thought I had given him at some point as a gift. Beside him were other men, who contemplated him with sad faces, as if they knew my father was talking about a dead man without knowing that he would soon be one of them, that he was going to enter a dark, bottomless well that everyone who dies falls into, but my father didn’t know it yet and they didn’t want to tell him. There were eleven men standing behind my father, as if my father were the sacked coach of a soccer team that had just lost the championship; one wore a jacket and tie, but the rest wore leather coats and one, a long scarf that seemed about to strangle him. Some of them looked at the ground. I looked at my father and couldn’t quite understand what he was doing there, talking in that cemetery on a cold afternoon, an afternoon in which the living and the dead should have taken refuge in the shelter of their homes or their tombs and in the resigned consolation of memory.

From the June 21, 2008, edition of El Trébol Digital:

Alberto José Burdisso lived aloan [ sic ] but left this world with a crowd. Because a multitude, crying out for justice, accompanied him en masse to his final resting place. Following the prayers for the dead in the parish of Saint Lawrence the Martyr, completely packed, a funeral procession several blocks long changed its route to pass by the Club Trebolense, where many, many people greeted it with applaude [ sic ]. The scene […]. After the first waves of applause, Dr. Roberto Maurino stated: “He got by the best he could, almost always suffering, and he left the same way because he got the worst of it in his last moments. Now, for eternity, into the unknown, Alberto will rest in peace. It was a great honor to be his friend.” […] The procession then finally continued with hundreds of cars. […] When the procession arrived at the local cemetery, several hundred residents walked with Burdisso’s coffin to its final resting place. There “Chacho” Pron, with warm and heartfelt words, also remembered Alicia Burdisso, Alberto’s sister, disappeared on the twenty-first of June of 1976 during the military Process [ sic ], in the province of Tucumán.

Читать дальше

8.21.1956 [or it could be 1958, the photograph wasn’t in sharp focus] / Your husband and children with love”; it was probably the plaque that covered the niche before the coffin was deposited, probably referring to the dead man’s grandmother or mother — but then, where is his father buried? — so perhaps it was a family crypt.

8.21.1956 [or it could be 1958, the photograph wasn’t in sharp focus] / Your husband and children with love”; it was probably the plaque that covered the niche before the coffin was deposited, probably referring to the dead man’s grandmother or mother — but then, where is his father buried? — so perhaps it was a family crypt.