Niall Williams

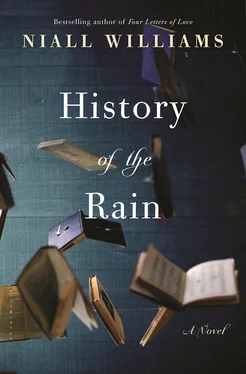

History of the Rain

Everything is on its way to the river.

Ted Hughes

ONE. The Salmon in Ireland

The longer my father lived in this world the more he knew there was another to come. It was not that he thought this world beyond saving, although in darkness I suppose there was some of that, but rather that he imagined there must be a finer one where God corrected His mistakes and men and women lived in the second draft of Creation and did not know despair. My father bore a burden of impossible ambition. He wanted all things to be better than they were, beginning with himself and ending with this world. Maybe this was because he was a poet. Maybe all poets are doomed to disappointment. Maybe it comes from too much dazzlement. I don’t know yet. I don’t know if time tarnishes or polishes a human soul or if it’s true that it’s better to look down than up.

We are our stories. We tell them to stay alive or keep alive those who only live now in the telling. That’s how it seems to me, being alive for a little while, the teller and the told.

In Faha everyone is a long story.

You anything to the MacCarrolls over in Labasheeda?

To begin you must be traced into the landscape, your people and your place found. Until they are you are in the wrong story.

My mother is MacCarroll.

I was thinking that. But you are. .?

Swain. Ruth Swain.

Swain?

We are our stories. The River Shannon passes below our house on its journey to the sea.

Come here, Ruthie, feel the pulse of the water, my father said, kneeling on the bank and dipping his hand, palm to current, then reaching up to take my hand in his. He put our arm into the cold river and at once it was pulled seaward like an oar. I was seven years old. I had a blue dress for summertime.

Here, Ruthie, feel.

His sleeve darkened and he rowed our arm back and let us be taken again, a little eddy of low sounds gargling as the throat of the river laughed realising what a peculiar thing was a father and his daughter.

When it comes to Clare, when it passes our house, the river knows it is nearly free.

I am plain Ruth Swain. See me, nineteen, narrow face, MacCarroll eyes, thin lips, dull hazelnut hair, gleamy Swain skin, pale untannable oddment, bony, book-lover, reader of so many nineteenth-century novels before the age of fifteen that I became exactly too clever by half, sufferer of Smart Girl Syndrome, possessor of opinions and good marks, student of pure English, Fresher, Trinity College Dublin, the poet’s daughter.

My History in College: I came, collapsed, came home again. Home — hospital, home — hospital, the dingdong of me. I have had Something Amiss, Something Puzzling, and We’re Not Sure Yet. I was Fine except for Falling Down. I have been Gone for Tests, Not Coming Right, Terrible Weak, Not Herself, and just A Bit Off, depending on the teller and whether loud or whisper, in Nolan’s shop or on the windowsill of Prendergast’s post office after Mass. For the record, I have never been Turning Yellow, never been complaining of the bowels, intestines or kidneys, never been spotted, swollen, palsied, never wetting, bleeding, oozing, nor, God-forgive-me, Bitch of the Brouders, raving. Mine is not the story. I am plain Ruth Swain, bedbound, here, attic room beneath the rain, in the margin, where the narrator should be, between this world and the next.

This is my father’s story. I am writing it to find him. But to get to where you’re going you have to first go backwards. That’s directions in Ireland, it’s also T. S. Eliot.

My father was named Virgil by his father who was named Abraham by his father who once upon a time was the Reverend Absalom Swain in Salisbury, Wiltshire. Who the Reverend’s father was I have no clue, but sometimes when I’m on the blue tablets I take off into a game of extreme Who Do You Think You Are? and go Swain-centuries deep. I follow the trail in reverse, Reverends and Bishops, past the pulpit-thumpers, the bible-wavers, the sideburn and eyebrow-growers. I keep going, pass long-ago knights, crusaders and other assorted do-lallies, eventually going as far back as The Flood. Then in the final segment, ad-breaks over and voiceover dropped to a whisper, I trace all the way back to God Himself and say Who Do You Think You Are ?

We are Swains. I read an essay once where the critic complained there was a distance from reality in Dickens’s characters’ names. He didn’t know Dickens couldn’t sleep. That he walked the graveyards at night. He didn’t know Moses Pickwick was a coach-owner in Bath, or the church register at Chatham lists the Sowerberry family, undertakers, or that one Oliver Twiste was born in Salford, and a Mr Dorrett was confined in the Marshalsea prison when Dickens senior was there. I know, weird that I know that. But if you lie in bed all day with nothing but books you won’t be Class One Normal yourself, and anyway Swains don’t do Normal. Open the phonebook for County Clare. Turn to S. Run your finger down past Patrick Swabb the hurling chemist in Clarecastle and Fionnuala Swan who lives by the vanishing lake in Tubber, and before you get to Sweeney there we are. Between Sweeney and Swan we’re the only entry, between the Bird King and the last daughter of Lir: Swain. The world is more outlandish than some people’s imaginations.

My actual great-grandfather I never met, but because of him the Swain side of the family are what Nan Nonie calls Queer Fish. Out of the mists of my night-time unsleeping I sometimes see him, the Reverend. He too cannot sleep and walks away from a shadow church at marching pace, striking out past a graveyard where the headstones tilt like giant teeth and the stars are bared. He cannot get where he is going. His burden is an intense restlessness that will not let him lie down, and so while his lamb-wife Agnes sleeps on the very edge of their bed the Reverend walks the night. He walks twenty miles without pause. From him escapes a low murmuring hum that may be prayers. Hands behind his back, he is like a man with Business Elsewhere, and none of those he passes, lost souls, rumpled shades, dare delay him. He has the Swain jaw, the sharp up-jut, the grey beard-line that though he shaves twice daily remains like a half-mask he cannot take off. I see him, pacing out past the yew tree in the churchyard. What his business is, where he goes to meet it and how exactly it is transacted are all enfolded in the mystery of ancestors. He can only be followed so far. Above the tree I sometimes throw a fistful of stars, hang a crescent moon, but for my moon and stars the Reverend does not pause; he paces on into the dark, and then is gone.

Just a brief shiver of great-grandfather.

What the Reverend bequeaths to our story is the Swain Philosophy of Impossible Standard. In the year eighteen hundred and ninety-five he leaves it to his son at the christening, dipping the boy into the large cold name Abraham , and stepping back from the wailing, jutting the jaw. He wants his son to aspire. He wants him to outreach the ordinary and be a proof to God of the excellence of His Creation. That is how I think of it. The basis of the Philosophy of Impossible Standard is that no matter how hard you try you can’t ever be good enough. The Standard raises as you do. You have to keep polishing your soul ahead of Entering the Presence. Something like that.

And Grandfather Abraham began polishing straight away. By age twelve, nineteen hundred and seven, he was a medal magnet. For Running, One Hundred Yards, Two Hundred Yards, Long Jump, Hop Step and Jump, Grandfather was your man.

Читать дальше