Because it says: Abraham gave up the ghost, and died in good old age, full of years; and Jacob is preparing lentils as funeral food for Isaac. Faint from the field, Esau comes upon his brother engaged in an act of filial, and grandfilial, devotion.

And by the way: the verb is seethe — seething pottage. Sod is the past participle.

Sisobk is disappointed. He had hoped to damn Jacob and the Sodomites together — drown them in the same sodding pottage. But invite the rabbis in and you can’t expect to have everything your own way.

‘Second question: Why lentils?’

Because we say: the roundness of the lentils symbolises death — grief and mourning rolling among us, now from this person, now to that.

Because we say: lentils have no mouths, and so remind the bereaved of their obligation to observe silence, to be mouthless, except on the subject of their bereavement.

Because it is said: Adam and Eve ate lentils after the murder of Abel.

‘I know his brother,’ Sisobk says. ‘He’s a tourist here. But that’s not my question. This is: Why seek a precedent for lentil-eating in violent death? Abraham will pass away quietly. Is it not said: Abraham gave up the ghost, and died in good old age, full of years?’

Yes, though not so full of years as he might have been. The Lord laid him to rest in the Cave of Machpelah at the age of one hundred and seventy-five. That is five years short of the number his son Isaac is going to attain. The reason for this charitable curtailment being, that the good old age promised, the contentment he looked forward to, would have been denied him at the last had he lived to see the evil wrought by Esau.

‘Third, no, fourth question: To wit?’

To wit:

The ravishing of an already betrothed maid.

The murder of Nimrod.

The casting of doubt on the resurrection of the dead.

The denying of God.

The lying publicly in his field with Canaanite women.

The lying privately in his bed with Canaanite women.

‘The fricasseeing of a dead dog?’

That is a folk-tale At least in so far as it is dramatically predicated on a scene of supernatural barking. The Lord does not, even for the purposes of admonition, take up residence in a stew. But there is a further obvious evil to add to the list:

The scorning of his birthright.

This one vexes Sisobk, though his dissatisfaction with it is as hard to find as his moustache.

‘If the occasion of Esau’s selling of his birthright is the morning of his brother’s sodding… seething pottage, and the pottage is in honour of the death of Abraham, then can’t it be argued that the continued existence of Abraham would have denied Esau the occasion for selling his birthright? And that far from Esau’s evil contributing to the demise of Abraham, the demise of Abraham contributes to Esau’s evil?’

From the darkest corners of Sisobk’s hovel comes the muttering of rabbis. Doubts, queries, counter-doubts and counter-queries, the unreasoning reasoning of men who read too many words. Then at last, a verdict:

You have not foreseen — O sciolist — how much the Lord foresaw.

Sisobk does not want to gloat, but he foresaw they were going to say that. He means only to be placatory, though. Scare away the rabbis and he has scared away his only company. ‘So in a sense then,’ he says, ‘in six, or is it seven senses, Esau is the murderer of his grandfather. But that still leaves Jacob as an opportunistic burglar of brothers’ birthrights.’

No, it doesn’t.

‘It doesn’t?’

He isn’t a burglar in the sense of hoping to secure material advantage to himself from what he takes.

‘He isn’t? Then what does he mean by saying, “Sell me this day thy birthright,” the price having already been set at a plate of lentils?’

In the first place he means: You are, by your own confession, faint — faint in your pursuit of venison and pheasant, and faint in your pursuit of God — and therefore you lack the will to perform such priestly services as go with your inheritance; which services, my brother, I, being a gentle and quiet man (tam in Hebrew), am prepared to do in your stead.

In the second place he means: You speak frequently, my dear brother, of your expectation of death — ‘Behold, I am at the point to die,’ you say — which I take to be an enunciation either of the daily fear that hunts you in the field, or the terror you feel in anticipation of your priestly duties; the job appears to be wasted on you in the first instance, and a burden to you in the second. Why do you not free yourself of unnecessary anxiety and let me bear your fears for you?

In the third place he means: Given your disbelief, my beloved brother, in God’s universal promise to resurrect the dead, and his particular provision of the Holy Land to the seed of grandfather Abraham, alav ha-sholem, what possible logic or profit can there be for you in your inheritance? Can a man inherit what is not to be? As I love you I would not see you the victim of moral subterfuge and theological sophistry. Permit me to wear the inconsistency for you, and pay you for that which, by your own reasoning, cannot come about.

Sisobk the Scryer laughs wildly. ‘So in truth,’ he exclaims to the familiar spirits of his room, ‘Esau is doing rather well out of the bargain. Considering how little he has to sell, he can count himself fortunate to be paid in lentils!’

But a premonition of sooner rather than later time snaps his neck back and clears the room, on the instant, of every trace of ghostly scholar. Not a hair remains. Not a thread from a fringe, not a quill, not a quarrel, not a quibble.

Sisobk hears the sound of footsteps on the streets, ringed fingers tapping on a copper pan. The fingers stop, tap and stop, teasing Sisobk’s hearing. Is he listening with his ears or with his heart? Is it now or is it soon? The tapping resumes, the ringed fingers no longer walking like feet but rapping like a fist. On the barred gates of the very building that hovels Sisobk. Soon. Sooner. Now.

‘That will be Cain,’ Sisobk remarks nonchalantly. And doesn’t even bother to clean up.

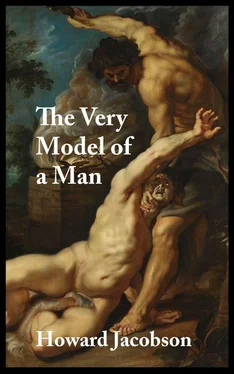

Has Cain come to the House of Hearsay and Hermeneutics intentionally, of his own free will? Or was it long ago settled for him in some other place that this was a visit he would have to make?

Has he fallen or was he pushed?

Ask Cain. ‘I was nudged,’ he will tell you.

He is disappointed that the House really is a house and not a cellar. Down down down down down should be down down down down down.

The building enjoys no particular eminence; it makes it to five or six storeys at best, but spreads, consuming whole streets, swallowing crossroads and corners, turning every edifice it touches, or looks at, into extensions of itself. It is plaguy and contagious. It is monumentally forbidding, great blocks of featureless grey stone laid one upon the other according to no principle except the order in which they were quarried. Like one of my father’s constructions for the accommodation of a field-mouse, Cain thinks, it looks simultaneously everlasting and on the very point of collapse. An immutable geometric law threatens to bury it under the weight of its own sloping walls. It has been built without regard to regularity or harmony, without considerations as to light or prospect, its guiding architectural assumption evidently being that those it is meant to confine will receive their illumination and perspectives from internal sources.

‘Like it?’ Sisobk is already at the gate, wearing one of those expressions of fractious surpriselessness favoured by men who know the end of things and grow weary waiting for others to catch up. ‘A wonderful invention of the civic mind,’ he says, gesturing to the dead walls. ‘Keeps light out and metaphysical rumour in. The authorities like to store all secrets of the heart under one roof, so they always know where they are.’

Читать дальше