Every time the neon tubes come on there's a powerful blinking but nothing really wakes up. The soldiers don't go away; they take off their boots and look at their toes. The waiting never comes to an end.

Asija and I are thirsty; they let us into Čika Sead's apartment. Nothing in it is closed, no door, no window, no cupboard, no dresser, no drawer — there's not a single secret left in here. Knives and forks and plates and cups and seasonings are lying on the carpet, and a single large shoe. Someone's poured milk into it.

I wash Asija's face.

Asija washes my face.

When we're back in the stairwell a woman soldier with a delicate nose, green eyes and bright red hair is standing where we were before, beside Čika Hasan, reading a book. The moments when the light goes off annoy the beautiful soldier and she hits the light switch. She pushes a sofa out of an apartment into the corridor and sits down right below the switch.

Once, just after the red-haired soldier has switched the light on, Asija nods in her direction and begins counting in a whisper. At a hundred and seventeen the light goes off. The redhead hits the switch. Next time we'll be faster, whispers Asija, and she glances at the switch on our side and begins counting again. Surely we just have to be ready for our switch to be faster, but we count, and later we can have a wish for every time we whisper the number at the same time the light goes off. At a hundred we put our hands behind our backs and on our switch, I never take my eye off the redhead on the other side of the corridor, at a hundred and five there's a burst of gunfire outside, at a hundred and eleven I whisper: we can't forget each other as long as we don't lose one another, at a hundred and seventeen the redhead laughs out loud, then darkness catches up with her laughter, I take Asija's hand, we press our switch together. In this victory, which makes her clap her hands in delight, Asija's smile is brighter than any light.

Quiet over there!

The woman soldier with the red hair wants to read.

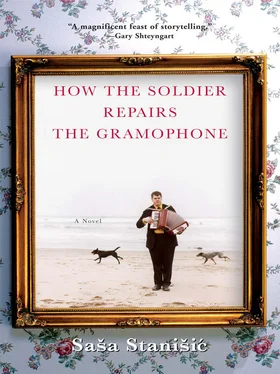

How the soldier repairs the gramophone, what connoisseurs drink, how we're doing in written Russian, why chub eat spit, and how a town can break into splinters

The mothers pour water into the hollows they've made in the flour, the soldiers shake hands saying good-bye, one soldier, with a gold canine tooth, asks: why don't we all wait for the warm bread? another says no, adding, to us: we're posting guards, I don't want anyone leaving this building after eight, don't make the street your grave, there are better graves to be found. Tired soldiers thump sleeping soldiers on the shoulder, nudge their noses with the sights of their rifles, up, up, time to march away, get up! The man with the gold tooth doesn't want to march away, he wants warm bread. But hands can't form the dough any more firmly, fingers can't knead it any faster, doesn't he know that? He doesn't know it, and it's no help when he asks Amela for soap, rubs the soapy water into his hands with a metal scourer, and buries his own fingers in the dough. He puts his arms around Amela's waist, he clasps her hands in his fists and kneads the dough that way. Amela with her hair in braids, and now some strands falling over her face too. With flour on her cheek and now an anxiously furrowed brow as the soldier listens to the nape of her neck, puts his ear against it, and from under Amela's braided hair tells the other women: you go out and close the door behind you — all of you, now! They close the door, lean against the wall, give each other cigarettes, spit on their forefingers, put the spit on the cigarette ends and wipe the tears from their cheeks. Amela, they whisper, Amela, Amela.

The soldiers were with us for an evening and a night, they stormed the building and then went straight off to see what they could find in cupboards and drawers. They drove everyone into the stairwell, shooting and yelling. The small children were crying all the time anyway, what with the noise in the stairwell and the plaster crumbling off the ceiling. The little ones cried for their mothers even though they were lying in their arms, were sitting on their laps, were already hugging them. Yells and fine plaster dust. And for Čika Hasan, ropes tying him to the banisters and a rifle butt at his neck: where's your son, old man, where's that misbegotten bastard?

The soldiers were with us through a twilit evening and an unquiet sleep; they slept on our beds, we slept in the stairwell. The guards woke us in the middle of the night; they were playing in the corridor with a chicken bone, two of them against two others. They had parked their tanks in the yard; their dogs had no names and were bad-tempered and fond of children.

The victors march away while the mothers bake bread. One of them comes out of Čika Sead's apartment, ducks his head under the door frame, no helmet in the world would fit that head, it's the biggest head ever, it would need a tub to cover it. A victor's skull like that must weigh as much as two stone slabs, and when the victor blinks a rockfall rolls out of his eyes. The victor shouts at his men and the red-haired woman soldier: there's some fun coming now, men, time to enjoy yourselves.

He's dragging a gramophone along behind him, he's taken hold of it by its trumpet and lifts it over the threshold as if taking a goose to be slaughtered. The gramophone is toy-sized in his great paw. Any moment now, men! He has Čika Sead's gramophone in his left hand, his shiny, polished Kalashnikov in his right. Any moment now, now, now. . his voice echoes in the stairwell, and the armed men and people who've been tied up listen. The victor with the biggest head in the world puts the pickup arm on the record, but nothing happens. Don't you dare! he shouts, hitting and kicking the gramophone. Right, men, I'll get it working in a minute! and he pulls at the knobs, works the switch, shakes the pickup arm, looks hard at the record, thinks it over and sticks the barrel of his gun in the horn.

If only I were a magician who could make things possible.

There's a crackling from the gramophone. When a hawk kisses a sparrow carefully so as not to hurt it, there must be a tiny sound like that. The needle engages in the groove: accordion! The tune is lurching along too fast, but now the victor adjusts the controls. It's the song everyone knows — nothing can stop you, you have to hug straight away. Normally you have to cling to each other, here and now while the music plays, holding each other tight as you keep in step! But no one moves, only the soldiers raise their guns above their heads and howl along with their dogs. Wailing and rejoicing: yoo-hooo! Shrill whistles, shouting in competition, yoo-hoo, louder, rata-rata-rata- ta. Soldiers take each other tenderly around the waist, two steps to the right, one to the left, yoo-hoo! The victor takes the beautiful redhead by the shoulders, shoots a question mark in the ceiling above her head — they all shoot in answer along with the refrain, and yoo-hoo! — in wild enthusiasm for the song. They're already swaying in a semicircle, four of them, five of them. Holding on to waists and shoulders: two steps to the right, one to the left, seven of them dancing down the narrow corridor. Two steps to the right — yoo-hoo! — one to the left, past Čika Hasan who whispers, sitting tied up there: what times are these when you have to fear dancing and close your ears to songs and music?

The accordion draws the soldiers further into their furious dance, caps are thrown on the floor — yoo-hoo! — now the voice of the woman singer is briefly heard and the soldiers join in: we're the voice! We're the gramophone! No one can hear the small children crying anymore — a whimpering among the throaty, thunderous sound of the army singing along, raging with joy.

Читать дальше