A good story, you'd have said, is like our river Drina: never calm, it doesn't trickle along, it is rough and broad, tributaries flow in to enrich it, it rises above its banks, it bubbles and roars, here and there it flows into shallows but then it comes to rapids again, preludes to the depths where there's no splashing. But one thing neither the Drina nor the stories can do: there's no going back for any of them. The water can't turn back and choose another bed, just as promises now cannot be kept. No drowned man comes up again asking for a towel, no love is found again, no tobacconist fails to be born in the first place, no bullet shoots out of a neck and back into the gun, the dam will hold or will not hold. The Drina has no delta.

And because nothing can be reversed, you'd have thought up yourself and us sitting on you eating, you'd have thought up pictures for the rain, and Granny putting a second cigarette in your earthen mouth, and then Great-Granny challenging me to a duel, let's see if you're finally my equal after ten years in the Wild West.

The rain is heavy and cold. Drenched to the skin, we carry the dishes and the soggy bread back to the house. I feel dizzy, there's no sky left. Great-Grandpa can't hold on to the wind anymore; it escapes, it grows stronger, in the yard one of the stones rolls off the table; the white cloth comes loose and takes off. GreatGranny stands still, not the good sheet, she murmurs, oh, not the good sheet. Great-Grandpa puts a hand to his back and laughs with the pain. The sheet flies through the rain, how can it fly when it's so wet, I wonder, but now it's landed at GreatGranny's feet, she winds it around Miki.

My phone rings. Great-Grandpa bends over with his hand on his back as if to pick something up, and I answer the phone: there's whistling and rushing and a woman's voice. What? I shout. No reply. The rushing becomes a rainstorm of voices, it's as if I were listening to two million phone calls at once. I can't follow any of them, feedback, the voices are gone. Great-Granny rolls Miki under the table. She wipes her hands on her apron and turns away. I put my other hand over my other ear and go out on the veranda, the roof over my head suddenly cuts off all the noises on the phone. I step back into the rain, crackling, I walk over the yard, slide down the slope, there's the woman's voice. Asija? I ask, softly at first, then louder: Asija? The answer, if it is an answer, comes blurred by rushing noises: Aleksandar.

Who is it? I ask, and my voice whistles, who's there? The echo comes back, I have to sit down, I've eaten and drunk incredible amounts, twice, I can't take any more, I let myself drop, I lie there among the sweet humming of a rain of voices. Where? howl two million voices at once. I feel sick. I can't cope anymore, above me the clouds, five or perhaps six feet above me. The rain fills my mouth, voices like flies in my ear.

Yes, I say, I'm here now.

Aleksandar? says the woman's voice, and it's a river I'm lying in, I have my own rainy river Drina now, and I say: yes, I'm here.

My thanks to Katherine Adler, Martina Bachler, Nadja Küchenmeister, Benjamin Lauterbach, Michael Lenz, Thomas Pletzinger, Ilma Rakusa, Simon Roloff and Leipzig for support.

My thanks to Goran Bogdanovic, Hamdo Opraic, Kristina and Petar Staniic, Mejrema and Hamed Hecimovic and Višegrad for the stories.

Without them, Aleksandar's eyes and ears would never have been so wide open.

My thanks to the Künstlerhaus Lukas in Ahrenshoop for peace and quiet, accommodations, and the dunes.

My thanks to the Cultural Department of the city of Munich and the Villa Waldberta for their confidence, for the sporting activities and the Starnberger See.

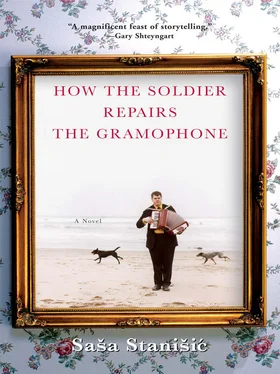

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone was sponsored by the Crossing Borders Programme of the Robert Bosch Foundation.