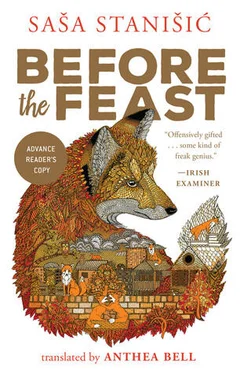

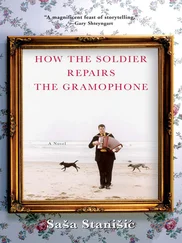

Saša Stanišić

Before the Feast

For billions of years since the outset of time

Every single one of your ancestors has survived

Every single person on your mum and dad’s side

Successfully looked after and passed on to you life.

What are the chances of that like?

The Streets, “On the Edge of a Cliff”

WE ARE SAD. WE DON’T HAVE A FERRYMAN ANY more. The ferryman is dead. Two lakes, no ferryman. You can’t get to the islands now unless you have a boat. Or unless you are a boat. You could swim. But just try swimming when the chunks of ice are clinking in the waves like a set of wind chimes with a thousand little cylinders.

In theory, you can walk round the lake on foot, keeping to the bank. However, we’ve neglected the path. The ground is marshy and the landing stages are crumbling and in poor shape; the bushes have spread, they stand in your way, chest-high.

Nature takes back its own. Or that’s what they’d say in other places. We don’t say so, because it’s nonsense. Nature is not logical. You can’t rely on Nature. And if you can’t rely on something you’d better not build fine phrases out of it.

Someone has dumped half his household goods on the bank below the ruins of what was once Schielke’s farmhouse, where the lake laps lovingly against the road. There’s a fridge stuck in the muddy ground, with a can of tuna still in it. The ferryman told us that, and said how angry he had been. Not because of the rubbish in general but because of the tuna in particular.

Now the ferryman is dead, and we don’t know who’s going to tell us what the banks of the lake are getting up to. Who but a ferryman says things like, “Where the lake laps lovingly against the road,” and “It was tuna from the distant seas of Norway” so beautifully? Only ferrymen say such things.

We haven’t thought up any more good turns of phrase since the fall of the Berlin Wall. The ferryman was good at telling stories.

But don’t think that at this moment of our weakness we ask the Deep Lake, which is even deeper now, without the ferryman, how it’s doing. Or ask the Great Lake, the one that drowned the ferryman, what its reasons were.

No one saw the ferryman drown. It’s better that way. Why would you want to see a person drowning? It’s not a pretty sight. He must have gone out in the evening when there was mist over the water. In the dim light of dawn a boat was drifting on the lake, empty and useless, like saying goodbye when there’s no one to say it to.

Divers came. Frau Schwermuth made coffee for them, they drank the coffee and looked at the lake, then they climbed down into the lake and fished out the ferryman. Tall men, fair-haired and taciturn, using verbs only in the imperative, brought the ferryman up. Standing on the bank in their close-fitting diving suits, black and upright as exclamation marks. Eating vegetarian bread rolls with water dripping off them.

The ferryman was buried, and the bell-ringer missed his big moment; the bell rang an hour and a half later, when everyone was already eating funeral cake in the Platform One café. The bell-ringer can hardly climb the stairs without help. At a quarter past twelve the other day he rang the bell eighteen times, dislocating his shoulder in the process. We do have an automated bell-ringing system and Johann the apprentice, but the bell-ringer doesn’t particularly like either of them.

More people die than are born. We hear the old folk as they grow lonely and the young as they fail to make any plans. Or make plans to go away. In spring we lost the Number 419 bus. People say, give it another generation or so, and things won’t last here any longer. We believe they will. Somehow or other they always have. We’ve survived pestilence and war, epidemics and famine, life and death. Somehow or other things will go on.

Only now the ferryman is dead. Who will the drinkers turn to when Ulli has sent them away at closing time? Who’s going to fix paperchase treasure hunts for visitors from the Greater Berlin area, in fact fix them so well that no treasure is ever found, and the kids cry quietly on the ferry afterward and their mothers complain politely to the ferryman, while the fathers are left wondering, days later, where they went wrong? Those are mainly fathers from the new Federal German provinces, feeling that their virility has been questioned, and once on land again they eat an apple, ride toward the Baltic Sea on their disillusioned bicycles and never come back. Who’s going to do all that?

The ferryman is dead, and the other dead people are surprised: what’s a ferryman doing underground? He ought to have stayed in the lake as a ferryman should.

No one says: I’m the new ferryman. The few who understand that we really, really need a new ferryman don’t know how to ferry a boat. Or how to console the waters of the lakes. Or they’re too old. Others act as if we never had a ferryman at all. A third kind say: the ferryman is dead, long live the boat-hire business.

The ferryman is dead, and no one knows why.

We are sad. We don’t have a ferryman any more. And the lakes are wild and dark again, watching, and observing what goes on.

THE FUEL STATION HAS CLOSED, SO YOU HAVE TO go to Woldegk to fill up. Since then, on average, people have been driving round the village in circles less and straight ahead to Woldegk more, reciting Theodor Fontane if they happen to know his works by heart. On average it’s the young, not the old, who miss the fuel station. And not just because of filling up. Because of KitKats, and beer to take away, and Unforgiving, Orange Infernoflavor, the energy drink that takes East German fuel stations by storm, with 32 mg of caffeine per 100 ml.

Lada, who is known as Lada because at the age of thirteen he drove his grandfather’s Lada to Denmark, has parked his Golf in the Deep Lake for the third time in three months. Is that to do with the absence of a fuel station? No, it’s to do with Lada. And it’s to do with the track along the bank, which in theory is highly suitable for a speed of 200 km/h here.

The lake gurgled. At first Johann and silent Suzi, up on the bank, thought it was funny, then they thought it wasn’t so funny after all. A minute passed. Johann took off his headband and plunged in, and he’s the worst swimmer of the three of them. The youngest, too. A boy among men. All for nothing; Lada came up of his own accord, with his cigarette still between his lips. Then he had to lend a hand with rescuing Johann.

Fürstenfelde. Population: somewhere in the odd numbers. Our seasons: spring, summer, autumn, winter. Summer is clearly in the lead. The weather of our summers will bear comparison with the Mediterranean. Instead of the Mediterranean we have the lakes. Spring is not a good time for allergy sufferers or for Frau Schwermuth of the Homeland House, who gets depressed in spring. Autumn is divided into early autumn and late autumn. Autumn here is a season for tourists who like agricultural machinery. Fathers from the city bring their sons to gawp at the machinery by night. The enthusiastic sons are shocked rigid by the sight of those gigantic wheels and reflectors, and the racket the agricultural machinery kicks up. The story of winter in a village with two lakes is always a story that begins when the lakes freeze and ends when the ice melts.

“What are you going to do about your old banger?” Johann asked Lada, and Lada, who is no novice at the art of fishing cars out of the lake and getting them back into running order, said, “I’ll fetch it one of these days.”

Silent Suzi cast out his fishing line again. He had barely paused for Lada’s mishap. Suzi loves angling. If you’re born mute, you’re kind of predestined to be an angler. Although what does it mean, mute? Saying his larynx doesn’t work would be politically correct.

Читать дальше