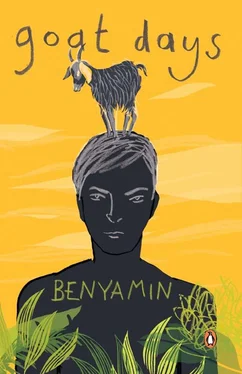

One day, while taking them for a walk, I hit one of them just once from behind. It turned back, like a cross elephant and snorted with all its might. I saw fumes coming out of its nostrils. The next moment, it charged at me, and without giving me a chance to evade, hit me right on the chest. It felt like as if a one-tonne mallet had hit me. I only remember flying off for some ten metres, like a villain hit by the hero in a Hindi film. I fell unconscious and don’t know how long I lay there like that. Then, when I opened my eyes, the arbab was in front of me. All the arbab did was pour some hot water on my face. Then he called me himar and shouted something.

Somehow, I scrambled up and looked around — the goats were scattered in a perimeter of nearly five kilometres. I became conscious of a terrible pain in my left hand. An immense unbearable pain. The hand was swollen. I told the arbab that my hand felt broken. He removed his belt and hit me, and shouted at me to run and fetch all the goats quickly. The arbab warned me that it would be my end if even one of them was lost.

I ran through the desert, literally carrying my throbbing hand. The goats were enjoying their unexpected freedom to the full, revealing all their wild characteristics. It was like a nation in slavery waking to revolt suddenly. Absolute chaos. When I somehow brought a goat to a side, the one already there would have run off. When I ran after the second, the first would have wandered off again. After a few tries I realized that it was impossible to gather all of them at one go. I began to run to the masara with the few I managed to collect, lock them up and rush back to the desert. Then, with the five or ten that I managed to gather, I would return to the masara again. The first goat would be about two kilometres away from the masara, and the rest scattered at about five kilometres from there. I am not sure how many times I had to cover the distance between the masara and the desert. I only remember that I was dead tired. And when I stopped to have some water, the arbab hit me hard, snatched the cup of water from me and flung it away. I rushed back into the desert again, thirsty, panting, my tongue parched.

Looking up at the sky with anguish, I whimpered the name of Allah all through that exercise. I could see goats scattered till the horizon. How was I going to get there? My feet were swollen, pain pierced my hand relentlessly and my thirst was severe. Screaming and shrieking, I ran after the goats. There was not even a hint of a wind, all was still in the sky and there was the blazing sun.

It was afternoon when I brought all the goats back into the masara. Later, I would often wonder how I survived for such a long time in that scorching heat without even a drop of water and with no rest at all. The two factors that helped me through that phase were my desire to live and my infinite faith in Allah. After bringing in the last goat, I fell on the cot, thoroughly exhausted.

The arbab came and sat near me and dripped some water into my mouth. ‘Water … water …’ I mumbled over and over again. Even in my half-conscious state I heard the arbab saying you people are profligates, profligates who do not know how to use water carefully. Then I lost consciousness.

It was night by the time I woke up. My hand was even more swollen and the pain was too severe to bear. I was sure it was broken. And my chest hurt from the pounding from the he-goat. My throat felt like it would crack from the thirst. I walked unsteadily to the water tank and drank to my heart’s content. Then I went to the arbab’s tent. Scolding me for sleeping for so long, he threw two or three khubus at me. I was very hungry. Dipping them in water, I greedily finished the khubus. I couldn’t sleep a wink that night because of the pain. I went crying to the arbab’s tent several times. I begged him to take me to any hospital. But the arbab didn’t pay any attention. As dawn broke, he came to my cot with a vessel and asked me to hurry up and milk the goats. I showed him my hand. I got a smack on my head as a reply.

The pain on my chest hadn’t eased and my hand was inflamed by then. I limped to the masara in that state. How could I milk the goats with just one hand? My usual practice with well-behaved goats had been to place the vessel on the floor and milk them with both the hands; the impish ones needed a rub on their back. What could I do with only one hand? If a goat jumped, it would kick the little milk I managed collect. Blindly, praying to Allah, I entered the masara. The first goat I saw was the one I had named Pochakkari Ramani. How I gave it that name is a story I shall tell you later.

I looked into Ramani’s eyes and told her, ‘Ramani, I cannot move my hand at all. It is the work of one of your partners. But the arbab must drink milk in the morning. It doesn’t matter to him if my hand is broken or if the sky has fallen. He must drink milk, and I must get it to him. If you cooperate, I will escape the beatings of the arbab. My fate is in your hands today.’

To tell you the truth, I have often felt that goats can understand things better than some humans. Anyhow, that day, Ramani stood still for me. Somehow, I got enough milk for the arbab and placed it in front of his tent. I cursed him in my mind: Drink pig, drink till you are full!

After gulping down the milk the arbab came to me and asked me to hurry up and milk the goats for the young ones. I simply wasn’t capable of that. I openly told the arbab, ‘I can’t! Can’t! Can’t!’ I think I was screaming by then. The arbab saw this side of me for the first time. He was really shocked. I went and lay face down on the cot, expecting belt lashes on my back. At the most, the arbab would kill me. Let him. This torment would end. What fear remains for one who is willing to accept death? Allah, I had promised to you and to your law that I would never commit suicide. I hope you will have no objection if I leave myself to be killed by the arbab. I am not fated to see my son. It is okay, I am not sad. Let me die at the hands of the arbab. I cannot take this suffering any more.

But the arbab did not come near me as I had expected. Already the goats had become restless and were jumping around. They were used to a schedule. If their routine was disrupted they got jumpy. Let everything go to hell. What do I care? I lay still.

When the elder arbab arrived, I did not get up. The two arbabs talked to each other. After that the day-arbab came towards me, took my arm and examined it. He massaged it through the swelling. Consumed by pain, I screamed loudly and begged the arbab to take me to a hospital. But he took his vehicle and went somewhere, as if he hadn’t heard me at all. I stretched out on the cot. He came back after some time with some herbs in his hand. Mashing them in a vessel, he applied it on the swelling, and then, like in olden times, took some sticks and fixed them tightly around my hand with a cloth bandage. I showed him the puffiness on my chest. There too he applied the herbs. All through the ordeal, I kept begging the arbab to take me to a hospital. All that the arbab said was ‘It is okay, you will get well soon.’ I did not trust him. I was afraid that my hand would worsen, rot and would have to be amputated.

The arbab brought me two or three khubus. Dipping them in water, I swallowed them. ‘It is already pretty late, quickly take the goats for a walk,’ the arbab ordered. I couldn’t say no. I ran to the masara, holding my broken hand.

By about noon, I could feel the pain slowly ease and fade away. It almost disappeared completely by night. Within just a couple of days, the swelling was gone, both on the chest and the hand. About ten days later, the bandage was removed. All those days, I milked the goats and took them for walks, with only one good hand. To my amazement, during that period, the goats never kicked or charged at me, or even toppled the milk pail.

Читать дальше

![Джон Харгрейв - Mind Hacking [How to Change Your Mind for Good in 21 Days]](/books/404192/dzhon-hargrejv-mind-hacking-how-to-change-your-min-thumb.webp)