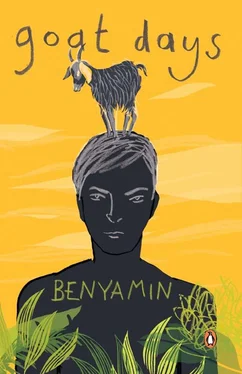

Although the arbab had been watching me work, he scolded me for not taking the goats out. I retorted that without help I could only do so much. The arbab answered me with his belt. A lash across my back. I squirmed in pain. It felt as though that lash would sting and hurt my back for the next six months. As he walked away, the arbab said something. I understood what he said — it was the work done by one person till I had joined the scary figure. At times a strange language can also communicate very well. I ran away crying and finished the remaining jobs. I didn’t get time to have breakfast, nor did the arbab invite me to have some.

I had just finished herding the goats of two masaras when the arbab called me and explained that a vehicle had come to take the goats to the market. ‘Catch the big ones and load them into the vehicle.’ It was my elder arbab who came in the vehicle. There was no one to help. I entered the goats’ enclosure. Standing outside, both the arbabs would select a goat and point at it, ‘ Aadi .’ I would try to catch it, but like a snakefish in water, it would slither away. I would follow it, catch it (How to catch … it didn’t even have any rope around its neck?), and take it up to the vehicle. The next problem was to push it inside the vehicle. I was not strong enough to carry it in. The goat wouldn’t get in willingly. I don’t know how much energy and time I spent on somehow pushing each one into the vehicle. By the time I managed two or three, I was worn out. But the arbabs made me scurry to the masara again and again. They would point to the masara and say, ‘Aadi abiyad. ’ I wouldn’t understand which one. Thinking that it was the goat next to me, I would try to catch it. ‘ Himar, maafi aswad, abiyad, abiyad, ’ the arbabs would holler. Realizing that it was not that one, I would try to catch a bigger one. ‘ Himar, mukh maafi inti, aadi abiyad ,’ the arbab would hit my head. Only after many mistakes did I finally realize that the arbab was asking me to catch the white he-goat.

Dragging it out, I somehow pushed it into the vehicle. Again, back to the masara. The arbab would say ‘ Aswad ,’ I would again commit some blunder before finally getting him the black goat he had pointed at. By the time I finished catching about twenty goats, I fell down, exhausted. I cursed myself and many others. The scary figure got his freedom. My reward: back-breaking labour! A lash that I would never forget! Starvation till lunch!

I was learning to face life alone, to train myself in jobs I had never performed before, to try out a new way of life, to get accustomed to an uncommon situation. It was not as if I had a choice; I was utterly helpless. Had we learned that one could get a little water only if one worked till one’s bones broke, we would work till we died, not just till our bones broke.

Since I had helped out the scary figure for a couple of days, I was confident that the routine jobs would not be difficult and that I could master them. Only the milking and herding of goats needed a little training; the rest even a blind man could do, all one needed was a bit of health and strength. At least that was my understanding. But, as the days passed, I had to learn many new things on my own — the ways of goats, how to rear them, the habits of camels. Circumstances can make a man capable of learning to do anything.

One day I was taking the goats out as usual — it must have been one week after my arrival — when I noticed that one of the goats looked sluggish and weary. It was pregnancy fatigue — like Sainu’s. When I’d asked the arbab if I should take it out, he had nodded his head in permission. After we were halfway from the masara, the goat moved away from the herd and lay down. Puzzled, I stood near it. After a while, it began to moan and squirm. Only then did I understand that it was going through labour pains. Although I tried to make it go back to the masara, it fell down after three or four steps. Meanwhile, the other goats were already scattered in the desert. As long as they moved in a herd, the goats acted fine. However, if the line got disrupted, if the herd scattered, it was all over. Then their instincts took over. Goats are the only domesticated animals that, despite living with man for about six thousand years, slip back into their wild nature whenever possible. That was why the scary figure had instructed me on my very first day to keep them in line and within the herd.

Before I could do anything, fifty goats had gone in fifty ways. I was in a dilemma: should I leave the one in labour and go after the rest or take care of it leaving the others to wander around? Finally, recalling the shepherd who goes in search of the lost one, leaving the forty-nine, I decided to attend to the goat in labour.

Forget goats, I had never seen any animal giving birth. I didn’t know what kind of help an animal in labour needed. I had never had any pets myself, nor had I cared for any of the animals that had lived in my neighbourhood. Therefore, my participation was limited to standing there, watching passively. After a while, I saw a head emerging and, with some horror, I continued to watch. Then involuntarily I ran forward to support the baby as it slowly began to come out, ingesting all the flames of pain. But because of the sliminess of its body, I couldn’t hold on to it. It fell off my hand, to the ground.

From somewhere, suddenly some old knowledge flashed inside me: the placenta should be removed! I cleaned its face and body with my hand. Its mother was even more conscious of her responsibility towards the kid than me. Within seconds, she licked the baby clean. Soon after its birth the baby began to try to stand up, and succeeded. It slowly tottered to its mother’s udders. I saw that it was a he-goat.

At that instant, my mind shook free of all its shackles and everything I had been trying to forget hit home. My Sainu is pregnant. When I left her, she was near delivery and I’ve had no news of her since. Maybe this was a good omen Allah wanted to show me. My Sainu, my wife — she has given birth. A baby boy, as I had longed for. In that belief, I named that newborn goat Nabeel. The name I had thought of for my son.

My hand and my dress were all wet with the water that broke and the blood from the placenta. Where could I wash? That the arbab would rebuke me if I returned to the masara without the goats was a certainty. I cleaned my hands on my robe and then I lifted that unsteady and beautiful little kid and kissed it. You are the present Allah gave me. Be well, my darling.

I took Nabeel to his mother’s breasts. Out of the blue, a swift blow flung me some distance away. Only when I regained consciousness after a few stunned moments did I realize that it was the arbab who had kicked me. He was looking at me with burning eyes and pointing at something as he hollered. The rest of the goats were scattered all over the desert. I mumbled a few words like goat, delivery, baby, placenta, etc. But the arbab was in no mood to listen. Angrily, he came forward and pulled my Nabeel away from his mother’s teats. Then, brutally disregarding my helpless pleadings and the mother goat’s heartbreaking look, he went back to the masara carrying Nabeel on his shoulders.

Leaving the mother goat there, I ran after the other goats. It was only after a great effort that I could somehow gather them. As I walked back with them to the masara, the mother goat followed us helplessly.

More punishment awaited me when I got back. I was severely beaten and reproached. The arbab accused me on four counts in that day’s charge sheet: one, I had tried to take some water to clean the placenta and blood off my hands and dress; two, I was late to return with the goats; three, I had wasted time by looking at a goat giving birth — goats know how to give birth and don’t need any human assistance; and, four, that was the most severe crime, I’d tried to make the newborn drink its mother’s milk.

Читать дальше

![Джон Харгрейв - Mind Hacking [How to Change Your Mind for Good in 21 Days]](/books/404192/dzhon-hargrejv-mind-hacking-how-to-change-your-min-thumb.webp)