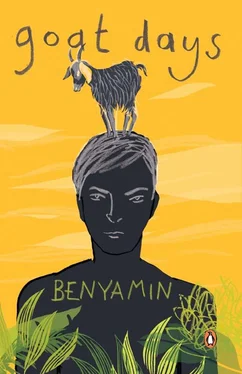

My discomfort kept me awake even though I was very tired. My thoughts were not of my home country, home, Sainu, Ummah, my unborn son/daughter, my sorrows and anxieties or my fate, as one would imagine. All such thoughts had become alien to me as they were to the dead who had reached the other world. So soon — you might wonder. My answer is yes. No use being bound by such thoughts. They only delay the process of realization that we’ve lost out to circumstances and there is no going back. I realized this within a day. Anxiety and worry were futile. That world had become alien to me. Now only my sad new world existed for me. I am condemned to the conditions of this world. I have fallen headlong into the anxieties of it, and it is better to identify with the here and now. That was the only way to somehow survive. Otherwise, my growing anxieties would have killed me or my sorrows drowned me. Maybe this was how everyone who got trapped here survived, no?

Can you imagine what I had been thinking about that night as I lay down? About going to the masara early in the morning and milking the goats; controlling the goats as the scary figure did and coming out with a vessel full of milk; the arbab’s face lighting up when he saw me with the milk; and single-handedly herding the goats of a masara and bringing them back. On how to go about realizing those dreams, and the precautions I had to take; about what my drawbacks had been that day, and how I could rectify them.

I neither bothered about yesterdays nor worried about tomorrows. Just focussed on managing the todays. I think all my masara life was just that.

Lying on my sheet, I tried to remember the Arabic words I learned that day and their meanings. It had only been two days. But I felt that I had learned more words than necessary.

arbab

saviour

masara

house of the goats

khubus

the only food that I might get here

mayin

a very rare liquid to be carefully used (Please do not trivialize it as mere ‘water’. What the arbab feels about mayin is not comparable to our attitude towards water.)

ganam

goat

haleeb

milk

thibin

grass

barsi

hay

jamal

camel

la

no

ji ham

yes, arbab

yaallah

get lost

It was only after recalling these words that I realized I didn’t know many more: wheat, vessel, tank, car, gun, desert, dress, bath, shit, loose motion, beating, anger, scolding, tent; and many verbs like came, went, didn’t do, do not know, etc.

If an Arabic expert among you asks whether the pronunciation and meaning of the words that I have tabled here are correct, I can only say I do not know. I’ve heard them like that, and have learned them like that. I was able to imagine a meaning out of those sounds. So, as far as I was concerned, that was the correct word and the correct pronunciation. After all, what is there in a word — it is understanding that is important. I could understand what the arbab meant by those words; and the arbab could understand me. One does not need to be a linguistic expert in order to communicate.

As I lay there thinking and musing over the past couple of days, time flew. Pain evaporated. Along with fatigue, sleep embraced my body. Deep sleep. Surely, it must have been past midnight by then. I woke up only after daybreak. The sun had opened his eyes in the east much before I opened mine. I woke up and looked at the cot. It was empty. He must have woken up early and got down to work, I thought. I ran to the masara hoping to be there before he finished milking. But the scary figure wasn’t there.

The goats had not been given water or fodder. The tanks had not been filled with wheat. Nothing had been done. Their routine disrupted, the goats were restless. I thought the scary figure was engaged in some other masara. I went around all the masaras. He wasn’t to be found in any of them. I wondered where he could have gone so early in the morning. I came out of the masara and sat on the cot. My mind was plagued by doubt, and I bent down and looked under the cot. The previous day I had seen a very old and dirty bag, one which I guessed was his. It wasn’t there! The sprout of suspicion grew.

Then the arbab came out of the tent and walked towards me. He gave me a vessel and asked me to milk the goats and get him milk. I looked at the arbab apprehensively. Surely the arbab must have understood the meaning of that look — where has the scary figure gone? Then the arbab told me a lot of things. His words were loaded with anger, curses, sympathy, cruelty, disparagement.

This is what I could gather from those words: he, my scary figure, had escaped from this hell!

We had been acquaintances for only two days. I don’t even know if he could be called an acquaintance. A few words were all that we had exchanged. Didn’t know his name, native place, nothing. Still, it hurt a lot when I realized he had gone. I couldn’t fathom the reason for that pain. It might have originated from the anguish of intense loneliness. Suddenly my body was overpowered by weariness. Like the sensation one feels when out of the blue one hears that one’s uppah or ummah or child has died. But my arbab, the messenger of the dismal news, had no feelings. ‘He’s left.’ Yes, he has. That was all. Where, how, with whom? ‘No,’ he said, as if he didn’t want to know.

Unexpectedly, I saw a ray of hope. The arbab would react similarly if some day he heard that I had also left. If the scary figure is gone, there is Najeeb, if Najeeb is gone, there will be someone else. That’s all.

But I was not as hopeful when I saw his attitude and activities on the first day. He shot at the sky with his gun, demonstrated the range of the binoculars, observed me from the top of his vehicle whenever I went out, and drove around me when he felt that I had gone too far. I feared he would never let me escape from this hell. I had observed that fear and precaution in each action of the scary figure. I could discern that fear in each word he uttered to me: Never attempt to flee. He will kill you if you do — that unkind, brutal, ruthless arbab. But after saying all those things to me, he had escaped. Liar! He had been waiting for me to join, had handed over everything to me and scooted. He served me all those lies so that I wouldn’t try to escape. Look, how calm the arbab is. Even his usual annoyance is not to be seen. Only an air of resignation, what’s gone is gone.

When I thought about my situation, I felt happy. One, the scary figure had somehow escaped from this suffering. Two, I too can escape like this in the future. Three, and most important, I am going to appropriate the cot. I would not have to sleep on the ground again.

As I got a whiff of freedom, I became very lively. I ran to the masara with the vessel and milked some goats. Of course, I was still an amateur, but I did much better than the day before and did not get as many kicks from the goats. I had come a long way from the previous day’s not-even-a-drop stage. But it would be some time before I was as good as the scary figure.

I gave some of the milk I got to the arbab, the rest I placed in the masara of the young ones. Then, I began the rest of the back-breaking work. I had to do the work of two people. The camels had to be fed and set free. I supplied enough grass, wheat and fodder to each masara, and filled the containers with water. Meanwhile, a water truck came, and I helped the man fill the tank; a trailer came with fodder, and I helped unload it. Although I worked hard, the jobs at hand were never-ending. Even when it was time to herd the goats (I had started guessing time from the length of the shadow), half the masaras hadn’t been supplied with grass.

Читать дальше

![Джон Харгрейв - Mind Hacking [How to Change Your Mind for Good in 21 Days]](/books/404192/dzhon-hargrejv-mind-hacking-how-to-change-your-min-thumb.webp)