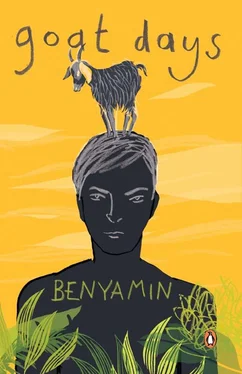

He cried a lot, recalling his ummah, uppah, relatives and Allah. I had no answers for him. I only had the strength to cry with him, holding his hands to my chest through the iron railings. The night washed away in tears.

It rained for two more days. The masara was filthy and full of muck by the time it stopped. The foul smell of goat droppings, urine, decaying hay and grass rent the air. It took me three or four days of back-breaking work to clean it all up.

Then the desert’s vaults were flung open for the winter. It was foggy and cold in the mornings. When I got up and looked around, all I could see was the white film of winter. Everything — the masara, the goats, the arbab, the tent — disappeared into that whiteness. It was only around nine o’clock that the fog faded and everything became visible again — though the hour is a guess on my part, for I was a lonely being with no sense of time — and, so, all routines were disrupted. During summer, the days were very long. The sun rose very early, by about three in the morning, and the light didn’t fade till eight at night. But in the winter, the sun didn’t rise till nine, and the light would fade just after lunch. By four it would be completely dark. So the hours one got to do work were limited. In the winter one had to finish work in about six to seven hours, the same work that took ten to fifteen hours in the summer. Moreover, it was hard to work properly because of the cold. Even at noon it was spine-piercingly cold. I could not even touch the water. My hands would become numb if I had to work with water. It was in those days that I learned that even cold water could burn skin. On one occasion, blisters appeared on my left palm as if it had been scalded with hot water, after it was in cold water for some time. I have heard that it is cold at the poles, but I don’t know from where such cold comes to the desert!

I didn’t have any special clothes to protect me from the cold. I only had that abaya, the long unwashed garment that the arbab had given me on my first day, which I never removed from my body. What I had was a woollen blanket left behind by the scary figure. I wore it during the first days of winter, but it was a bother. How could one run after goats and enter the masara to fill the containers with water or hay wearing a blanket? I gave it up. It became my habit to walk in the cold in that single piece of clothing.

Though I discovered it a little late, there was something that gave me heat even in the height of winter: sheep! It was a real comfort to walk among them. When the cold wind came whistling, I would hold the sheep close to my body. Whenever the cold pierced through the blanket to maul my body, I would go to the masara and lie there embracing the sheep. I spent the winter as a sheep among the sheep.

Apart from the raucous wind, another unwelcome guest came to the masara in winter: flies. There were flies all around. A thousand flies would sit on the khubus when it was taken out. One hand had to be free all the time to keep them away. If one went to the masara, one could hear them buzzing like wasps. Though I disliked those wretched flies, I began to think that they too had to live somewhere. And if they liked the masara the most, then let them live there!

That winter, had I wanted, I could have escaped along with Hakeem, taking cover in the heavy mist. But the same doubt that I had on the first night of rain cast a spell on me, paralysing me from making my escape. Where to go? I did not know anything about this country, not even about the area I was in. In which direction — east, south, west or north — should I run to find a way out? Here, surely, I didn’t have enough food, water, clothes, a proper place to sleep, wages, dreams or aspirations. But I did have something precious left — my life! I had at least managed to sustain that. If I ran away into an unfamiliar desert I might lose even that. Then what would be the meaning of all that I had endured so far?

Every prison has its own aura of safety. I didn’t feel up to bursting that bubble of security. I decided to wait for the appropriate opportunity to strike — when I was sure of reaching a safe location. Was my decision correct? I didn’t know.

At the beginning of winter more sheep had been offloaded in the masara by trucks. It was their breeding time, the six months till summer. Actually, sheep survive best in cold, mountainous climates. Rearing them in the desert is an injustice to them. The desert is congenial to goats as they can endure the high temperatures. The arbab kept the sheep because of the profit he made from selling their wool. Although three-quarters would be sold by the time summer came, the ones that remained, suffered. As the temperature soared, they died sweltering in their own woollen coat. I witnessed this many times. The arbab didn’t throw away any of the corpses. He’d drag them into his vehicle and drive away. They must have been served as fresh mutton in some restaurant or the other later.

One day, when the winter was coming to an end, two men came to shear the sheep. They were Sudanese and both of them had broad smiles. Filled with the joy of meeting people after a long time, I followed them around like a puppy. But they didn’t understand much of what I said and neither did I make sense of what they said. But it was with broad smiles that they remained uncomprehending of my words.

That year the Sudanese came with a machine to shear wool and a generator to work it; previously they had used hand-held scissors. The arbab began to jump around like a troubled jinni as soon as they started the generator and the machine. His first fear was that his sheep would get electrocuted. The poor men had to struggle to convince the arbab that the machine wouldn’t kill the sheep with electric shocks. The arbab’s second fear was that the machine would shear more wool than necessary and the sheep would burn to death in summer. (There would be no demand for such sheep in the market.) It was only after they had demonstrated on a sheep that the machine was set to shear only to a certain thickness that the arbab half-heartedly gave his consent. Even then he continued to express his displeasure at the use of the machine.

It was my duty to secure the sheep for shearing. I had to do that after carrying out all my daily chores. I held the sheep by their necks between my knees, like I had the kids that were castrated. It took hardly a minute or two to finish shearing one sheep, but it was a back-breaking job for me to hold some six hundred of them like that over two days. The machine would shear the sheep bare, only leaving some wool on its tail. ‘This is how we shear in our land. The tail hair is our gift to the sheep to swat flies,’ the Sudanese smiled, showing his white teeth.

All the sheep were shorn by the next afternoon and they looked like gorgeous lads and lasses. By evening, the Sudanese packed the wool in sacks and left in their pick-up. The sense of dejection that descended on me as they departed! I had been enjoying the scent of two humans till then. Now, there were only the animals and me. Grief came, like rain.

Winter was also the time when I learned that it was impossible to wipe out life on this earth whatever man’s misdeeds. For how many months had this desert been lying under scorching heat! There had been no sign of life on those burning sands. As the cold wind blew, signalling summer’s end, a green carpet surfaced on the dry sand. This was within two days of the rain! It was as if all the scents of life had been lying dormant beneath that brown surface, straining to hear the music of resurrection: cactuses, creepers, rock fungi, touch-me-nots, bushes with shiny leaves. And from the ends of the sky came flocks of birds that spread their long wings, warbling swallows, chattering green parrots, pairs of cooing doves. Where did they all come from?

Читать дальше

![Джон Харгрейв - Mind Hacking [How to Change Your Mind for Good in 21 Days]](/books/404192/dzhon-hargrejv-mind-hacking-how-to-change-your-min-thumb.webp)