The Mayor made himself at home. He harvested the garden produce, fed the goat, forged signatures. After his mayoral work was done, he drank beer on the balcony and looked at the sky more often than the lake. He knew he was seeing stars that had been extinguished long ago, and that weighed on his mind. Was it a sign? And if so, what of?

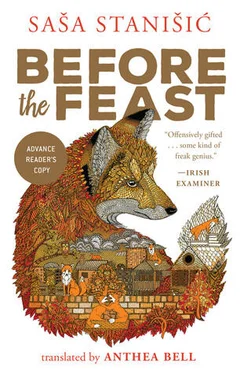

If you are building a chicken run, make the entrance tunnel go in a zigzag, with short straight bits and sharp angles, so that a chicken can get along it easily, but not a fox. And get a dog with a nervous disposition.

The circumstances of Durden’s move were dubious, but we and the time were not yet mature enough to point out such a thing in public. Furthermore, the village had worse problems than the Mayor’s house-moving: to name just one, liquid manure trickled down from the arable fields into the lakes, making their ammonium content twelve times more than was permissible. Children ran into the water and came out itching. Blue-green algae increased and multiplied like rabbits. No one in the Agricultural Production Society was interested in that; even Durden had once tried mentioning the matter, and got nothing but promises.

There was one small comfort. The pike-perch from the Great Lake were sold in the West. People were annoyed about that, rightly so, but not quite so annoyed when the business of the ammonium content came out, and of course we didn’t wish severe nausea on anyone over there — but even a Wessi, we thought, can take a little bit of nausea if there is any.

If you are building a chicken run, use sturdy, close-meshed wire netting. You don’t want the fox to be able to climb it or bite a hole in it. Fix the lower one-third of the netting properly to a low concrete wall that continues underground, preferably for half a meter down. The fox digs fast and well. Don’t build the little wall too high; chickens need light, and should be able to see what is on the other side of the wall. Artificial light makes them nervous.

Durden had a garden makeover. He wanted more tidiness, more pumpkins and melons, fewer blackberries and indeed fewer berries in general, because berries are kids’ stuff. He didn’t like the goat, but he kept her because she licked his hand even when there was nothing in it.

One day he went with the local branch of the Small Animal Breeders’ Association to the district show in Sarow, and saw Dietmar Dietz, known as Ditzsche, win the crowing contest with his Dwarf New Hampshire rooster, which crowed 151 times within an hour, and then win the green victor’s ribbon too in the Dwarf Chicken class, with a blue-porcelain colored fowl that had feathered feet.

Now Durden wanted dwarf chickens too.

Ditzsche thought it was a joke, but Durden’s eyes were shining. The Mayor wandered past the pens. Feathers shimmered in the most wonderful colors, and he pointed in silence to one of the fowls now and then, if he particularly liked it.

Ditzsche tried to dissuade him: it took a lot of time and trouble, he said. Breeding pedigree chickens called for care, good rearing and, yes, love.

Good rearing, said Durden, reaching out to a hen, would not be any problem. And after today he felt any amount of love for these proud creatures.

Ditzsche didn’t like to hear chickens called proud. Their swelling breasts, raised heads and erect bearing are physical and not mental attributes.

The Mayor stopped outside one pen with a solitary rooster in it, blue-black, with a golden back and a bright red comb, stalking thoughtfully about in circles. The little man linked his hands behind his back and walked round the pen, instinctively imitating the bird.

“An Old English Dwarf Game Fowl,” said Ditzsche.

“Old English,” whispered Durden. “Game Fowl,” he whispered. “How many hens does a rooster like that need?”

The rooster stared at Durden, or the sky above Durden, and fluffed up his plumage. The decision was made.

If you are building a chicken run, think about electricity. However, remember that an electric shock will irritate the fox but not drive him away for ever. Foxes do not give up before they have reached their limits. Count on needing at least 3,500 volts. The electric wiring is fixed on the outside of the enclosure. Only chickens that leave it are endangered.

Durden wanted to put up an enclosure for his chickens. Ditzsche offered to help him, and warned him about the fox. Then it must be secure, said Durden. Ditzsche told him about keeping chickens, told him about the fox. Durden drew a plan. Ditzsche improved the plan and got hold of the materials. They built the enclosure together. Two days later the chickens were delivered. Three of them were killed the following night.

When Durden discovered the massacre in the morning, he summoned Ditzsche and demanded an explanation. Ditzsche examined the scene of the crime. The chickens had been killed in their henhouse. The fence was intact, there were no holes in the ground. Then Ditzsche noticed the goat. She was grazing close to the fence; Durden had tied her up to its corner post overnight. Ditzsche studied the animal. He found reddish hairs on her back. He showed them to Durden.

What the hell did that mean, Durden asked.

Ditzsche smelled his fingers. “Fox. The goat is too close to the fence. The fox used her as a springboard.”

Durden, lost in thought, repeated the word “springboard” several times. In an even voice, rather too even a voice, he then asked why Ditzsche, with his alleged knowledge of the subject, hadn’t taken this eventuality into account.

Ditzsche had no answer. A surviving hen clucked quietly. Durden compressed his lips; his chin was shaking. “How are they ever going to trust their home now?” he whispered, as if he didn’t want the hen to hear him. “They’ll always be thinking they hear a beast of prey outside. Instead of the hand that feeds them they’ll expect the jaws that eat them. Those chickens,” said Durden, clutching the wire netting of the fence, “can never be happy again.”

Once your chicken run is up, let two roosters fight for the hens. The winner will protect his hens all the better the harder he had to fight for them. He will warn them when danger threatens, and the hens will take refuge in the henhouse. If a fox threatens the hens, the rooster will sometimes save their lives, but often he will not.

Durden refused to pay Ditzsche even for the materials. In the village he told everyone how that idiot had cost him three pedigree fowls, and blamed it on a goat. He didn’t tell the story himself, of course. He had other people do that for him.

The gossip did not win out. Foxes eat chickens, full stop. If I were a fox, said the village, I guess I’d find pedigree fowls particularly delicious. Instead of talking about Ditzsche, people discussed possible ways of fox-proofing a chicken run. The ferryman said, “Ditzsche is above suspicion when it comes to chickens,” and the ferryman’s word had always carried more weight than anything the top brass of the village said. The matter was forgotten. Except by Ditzsche.

Once your chicken run is up, sprinkle plenty of pepper round the fence. Put human hairs in the netting at close intervals, rub your sweat on the fence. Urinate regularly near the enclosure.

Durden once joined us when we were drinking at Blissau’s. It was late, some of the customers were falling asleep at their tables. Durden began talking about his chickens. He could hear them clucking all the time, he said, even now. They complain, he said, they’re feeling sorry for themselves. They’re not happy.

The little man was remorseful. He ran his hand through his hair, ordered a beer and didn’t drink it. We comforted him, because everyone deserves comfort after midnight. We said the chickens aren’t sensitive to feelings. They don’t regret anything. They ask only for the necessities. Durden either listened or he didn’t. He lay down to sleep at home, and in his mayoral dreams he heard the Dwarf Game Fowl clucking.

Читать дальше