We are surprised that no stories are growing and proliferating around the room in the cellar. That sort of thing usually happens when we come across cellars, locked rooms and open questions. We take a historical interest in the non-proliferation of stories. For instance, why Paul Wiese’s entry on House Number 11, today the Homeland House, ends with an incomplete sentence: In the cellar of the house I found, in a small room . .

We take an interest in incomplete sentences.

We take an enormous interest in when the window of the Homeland House was broken into, and who it was that Uwe Hirtentäschel saw from his studio moving around: the shape of someone, and a beam of light traveling over the wall.

Now that, yes, that is really interesting.

IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD 1592 THERE WAS A VERY wet summer, during which Season the Rain fell in Cloudbursts, and the Fields and Meadows were flooded, Gardens laid Waste, and the Great Lake rose so high that the Carp in the Pond swam out of that Same. Cattle and Sheep also contracted the Rot, of which many did die, and whole Flocks and Herds perish’d, and the same was noted of Hares. Then there was in the Autumn a terrible Drought, making the Land intractable to work and Harvest very poor. The People, being in great Want, fear’d the Winter, and Famine threaten’d.

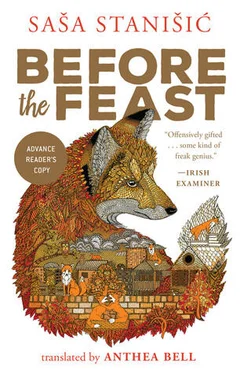

On the Morning of the second Day of November, however, there appear’d under the Oak Tree hard by the Church five Wagons full of Grain, Butter, dried Meat and Beer, the Origin whereof None could explain. The Church expected Prayers of Thanksgiving, yet it remained empty. However, a Quarrel had broken out concerning the rightful Owner of the Food, in uncouth and unChristian Fashion, like the Brute Beasts, and a Fox was even to be seen watching, Every Man took what he could carry, and tried to trip up his Neighbor who was carrying more.

But Joy in the Booty did not last long; that Miracle fail’d as quickly as it Came. The Foodstuffs vanished once more from Cellars, Storehouses, Chambers and Halls, sometimes even from Tables.

Where did it go? None could say.

And why? Some guess’d, and came to Church in a penitent Condition.

UWE HIRTENTÄSCHEL LEAVES THE PARSONAGE AND steps out into the night, only for a moment, but long enough to be drawn into our round dance. The ferryman takes his left hand, we take his right hand. Let’s just give him a moment to update his placard on the oak in front of the church.

On 21st September, at 5.30 p.m., the new basic course on the Christian faith begins at Fürstenfelde parsonage. We will devote ourselves to the subject of “Rapture” on the occasion of the Anna Feast. More information available from: heilands@freenet.de

Above the date he wrote in red marker: TODAY!!! and added a * before the T.

Uwe Hirtentäschel looks after the church, keeps it clean, encourages other people to visit it, talks to them benevolently about the faith. He provides them with candles and incense sticks, plays the saxophone in front of the altar, and after the service he leaves the radio playing, so that silence won’t seem to descend so suddenly. He takes care of the place, and that’s good; taking care of things is always good.

Hirtentäschel’s business card shows Jesus as the Good Shepherd, surrounded by sheep, holding a little lamb in his arms. If you tilt the card Jesus raises his arm and the lamb raises its head. On the back is the bit from the Gospel of St John about Jesus being the light of the world, so we must follow him and not walk in darkness.

Uwe Hirtentäschel has been saved. Either the ferryman or an angel saved him. Hirtentäschel is grateful for that every day. Every day, except when the weather is bad, Hirtentäschel puts up a folding table under the oak by the parsonage well, and serves tea and biscuits. All are welcome. Frau Schober made him a crochet tablecloth. She and Frau Steiner usually sit at his table, because they just happen to be in the area. They are both on the point of retiring, but Frau Steiner is very well preserved. She still does some newspaper delivery rounds to make ends meet, and Frau Schober sews and crochets. And then they sit at Uwe’s table in the middle of the day. There’s not much else going on at that time, the house is empty anyway, the Ossis on the midday TV program are always a bad lot and incorrigible. Only in the evening are there normal Ossis like you and us on TV, in Police Call and athletics and Wife Swap . The church oak tree provides shade in summer, and the optimism of the reformed Hirtentäschel provides warmth in winter.

Hirtentäschel puts the marker away and sets off for the parsonage. It is in Karl-Marx-Strasse, of all places, on the corner of Thälmann-Strasse. He has a small apartment and his studio on the top floor. Hirtentäschel’s latest work of art, done for the Feast, is stretched between the branches of the oak. It consists of white scarves. Frau Schober likes the scarves but doesn’t know what they are meant to be. It would be embarrassing to ask the artist in case she looked stupid. She would far rather have been able to say, “What lovely, lovely angels’ wings!” than be guessing, “Are those half-moons?” Or, “Is the white something to do with heroin?” To be honest, we don’t know the answer either, but they make a nice noise fluttering in the wind.

Uwe Hirtentäschel speaks softly and hardly ever asks questions. He wears only white or black clothes, to reflect the light and shade of his life story. He doesn’t mind showing his bald patch, and his glasses have thick lenses because he’s almost blind. That comes of the heroin. It was blinding him for years, he says, both spiritually and literally. Remarks like that show how serious his conversion is. It’s easy and pleasant to listen to someone who hardly ever tries to be funny.

Up on the top floor of the parsonage, Hirtentäschel goes on making his little figures of angels. He’s tired, but he will carve one or two more, one or two more tonight.

The village knows and likes the story of his enlightenment. He also tells it, unasked, to tourists when they stay to drink tea after looking round the church. He likes telling the story, because it was more important than anything else in his life, and because all of us — if we’re honest — are waiting for a miracle, so we like to hear about one.

Uwe Hirtentäschel was born in Fürstenfelde, and at the age of fifteen he ran away from Fürstenfelde. He describes the next fifteen years as a single moment and a never-ending trip. It had been a time full of small flashes of enlightenment in his drugged intoxication. He calls them “disorientations”: false, uncertain joys, siren songs. Sins. But then he had his great epiphany, when he was “found.” It happened in Fürstenfelde.

After years of taking drugs and addiction, Hirtentäschel passed the Woldegk Gate on his way to the Baltic early one morning, and there was the old wall, there were the lakes, there was the promenade, there was the ferry boathouse, all the same as ever, and he got out, had to get out, sat down beside the lake and drank perhaps his sixth beer of the day, and then the ferryman came by. He recognized Hirtentäschel. He recognized the boy who had just disappeared one day, leaving his parents with a thousand questions. The ferryman didn’t know about the disorientations, says Hirtentäschel, but he surely recognized his, Hirtentäschel’s, demons.

He took Hirtentäschel out on a boat trip with him and insisted on his lending a hand. As soon as someone comes back, Hirtentäschel cried, you want them doing your work for you, but the ferryman thought that was funny. Hirtentäschel rowing, all skin and bones. He found it terribly difficult. In the middle of the lake he couldn’t row any more. Then the ferryman made him promise something. He wanted Hirtentäschel to listen to him, he wanted to tell him a story. Hirtentäschel agreed, and listened, but he couldn’t concentrate, and to this day he doesn’t know what the story was about. They had reached the little island with the barn on it. Hirtentäschel got out, and as soon as he turned round he saw that he was alone, surrounded by tall grass and insects. “I called to the ferryman, but only a jay answered. I wanted to get back to the water, but the water had disappeared too, I couldn’t find the water any more, imagine that, and you’ll know what a bad state I was in.”

Читать дальше