I saw Mesari and someone else going up to the roof with Abdelmalek. I walked back to my table, and Afiouna sat down with me. He filled the sebsi , lit it, and handed it to me, saying: Here. Take it and smoke. It’ll make you feel calmer.

I’m not drunk, and I’m not m’hashish , I told him. This isn’t the first time I’ve had alcohol or majoun .

Then Grida went upstairs.

Nobody said you were drunk or kiffed , Afiouna said.

They think I am.

We all drink and smoke kif , he said.

I smoked the pipe and coughed a little. Afiouna got up and brought his glass of tea from the table where they had been sitting. I took a sip from it, and stopped coughing.

I’ve won the argument, I thought to myself. The other men in the café were discussing the altercation, and I noticed that certain of them agreed with me. They must already have felt the same way I did about Abdelmalek.

Grida came down the stairs, followed a moment later by Abdelmalek, Mesari, and his friend. Abdelmalek had washed the coffee from his face and clothes. Grida came over to me. You’ve got to make peace between you, he told me.

Yes, said Afiouna. Get up and talk to him. We’re all friends here.

They insisted, and I rose. Mesari and his friend pushed Abdelmalek towards us, and we embraced. I turned to go back to my table, but they made me sit down with them.

Come on, Si Moh, give us something to drink, said Grida.

Kemal came staggering back into the café. He had a black eye.

Kemal! I said. What happened to you?

Moh stared at him with annoyance.

I got up and went over to him.

There were two of them, he said. They jumped on me. At a whorehouse in Bencharqi.

Why?

They took me for a Christian. They wouldn’t believe I was a Moslem. They said how could I be a Moslem if I didn’t speak Arabic?

But why?

I wanted to take a Moroccan girl into bed.

All that trouble for a common whore, I said. Come and sit down with us.

No. You come with me.

Where?

We’ll go to the Zoco Chico and have something to drink. Mahmoud lent me a little money.

I excused myself to Abdelmalek and his group, and went out with Kemal.

We went to the brothel run by Seoudiya el Kahala.

I know the woman who runs the place, I explained. And all the girls.

Hadija Srifiya let us in. She took us into a room and we sat down. Soon Seoudiya el Kahala came in and greeted me. I introduced her to Kemal.

Es salaam , he said.

Is he a Moslem? she asked me.

Naturally he is.

Does he speak Arabic?

No. He only knows a few words.

But how can he be a Moslem if he doesn’t speak Arabic?

I told her there were other countries where the people were Moslems but spoke other languages.

Ana Muslim , Kemal told the two women. Allah oua Mohamed rasoul illah .

We all laughed. Sit down, Lalla Seoudiya told us. Do you want Hadija to stay here with you?

I asked Kemal. Of course she should stay, he said. Tell her to bring another pretty one.

We ordered a bottle of cognac and a bottle of soda water. I told Hadija to find us a girl who liked to drink and talk. The two women went out.

Do you like that one? I asked Kemal.

She’s perfect. Moroccan girls look a lot like Turkish girls, you know.

Hadija came back carrying a tray with the drinks. Sfiya el Qasriya was with her.

She greeted me. How are you, handsome?

I introduced Kemal, and she sat down beside him.

The drinks are a hundred and twenty-five pesetas, said Hadija.

And if we add you two to the bill, how much will it be? I asked her.

She looked at Sfiya and giggled: Three hundred pesetas.

How much? Kemal asked me.

Three hundred altogether, for them and the drinks.

He pulled out two 100-peseta notes. This is all I’ve got, he said.

I took the two bills and added another. Call Lalla Seoudiya, I told Hadija.

Give me the money, she said. Don’t you trust me?

It’s not that. I just want to get everything straight with Lalla Seoudiya.

Ah! I see. Well, do as you like.

Sit down, I said. I’m going to fix it up with her.

I went out of the room in search of Lalla Seoudiya. She was sitting in a far corner of the patio. I want to pay you now for the drinks and the girls, I told her.

You know how much it is, she said. Two hundred and fifty pesetas. That’s the price I make especially for you, because you’re an old client.

I gave her the money, and asked her to have me called at half past six in the morning. I explained that the four of us would be using the same room.

When I got back to Kemal, he had Sfiya’s head between his hands, and was stroking her cheeks and kissing her tenderly. It’s as if he was afraid she was going to get away, I said to myself. Perhaps some day I’ll sleep with a Turkish girl.

Hadija wanted to know if I had got everything arranged with Lalla Seoudiya. I folded a fifty-peseta note very small and slipped it into her hand, saying: Keep it. It’s for you. Everything’s all settled. She stuffed the money into her bodice and kissed me on the cheek.

I was just dropping off to sleep when Hadija, lying beside me, said: Did you hear that? Sfiya says your friend the Turk is licking her with his tongue.

Let him do what he likes with her, I said.

I’d rather have a tongue lick me than a zib massage me, Sfiya called out. The two girls laughed.

I want to go to sleep, I told Hadija. I’ve got to get up early and go down to the port.

Don’t worry, she said. I’ll wake you up as early as you like. I’m a light sleeper. She turned towards me and hugged me. Then she pushed my bent knee between her legs and began to rub herself against it. She wishes it were a zib , I thought.

Sfiya had started to moan, and Hadija increased her efforts against my knee. Suddenly she pulled at my hair violently. Then she relaxed. Kemal and Sfiya were laughing together.

Hadija turned over and lay face down. I put out my hand and ran it lightly over her buttocks. She was still pushing herself slowly back and forth against the mattress. I became excited again, and jumped onto her back for a ride. She tried to throw me from my seat, but I held tight and stayed astride. I pretended to myself that if I were unseated I should fall into emptiness. I was on a flying she-camel high over the desert, and to fall off would mean being lost in the wilderness.

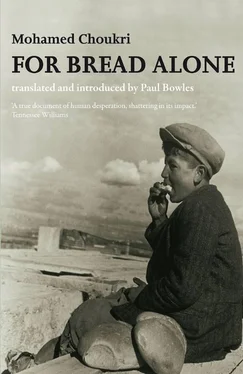

In the morning when I returned from the port I went into a bookshop in Oued el Ahardan and bought a book that explained the essentials of writing and reading Arabic.

I found Abdelmalek at the Café Moh with his brother Hassan from Larache. I apologized again for what had happened the night before. Forget it, he said. I was in a bad mood too.

They asked me to sit down with them, and I showed Abdelmalek the book I had bought. I’ve got to learn to read and write, I said. Your brother Hamid showed me a few letters while we were in the Comisaría together. He said I could learn easily.

Why not?

Would you like to go to school in Larache? asked Hassan.

School? Me? I said surprised. It’s impossible. I’m twenty years old and I can’t read a word.

That doesn’t matter. I know the head of a school down there. I’ll give you a note to him. He’ll take you. He has a soft spot for out-of-towners who want to study. If I didn’t have to go to Tetuan with this trouble I could take you myself to see him.

He paused, and then said: Why don’t you go and buy an envelope and a sheet of paper, and I’ll write you the note.

I did not believe in any of this, but I did as he suggested, and hurried back to the café. He laid the sheet of paper on top of a periodical, and began to write. From time to time he stopped and smoked a pipe of kif with us. When he had finished he folded the paper and put it into the envelope. Then he handed it to me.

Читать дальше