His mother too, when she talks about his birth. She says it was a ‘rough’ delivery. He was a ‘whopper’ who refused to budge. Then they brought the forceps and they pulled him out by his head. Yes, by his head. Then she ‘tore open’, she says. ‘Never again.’ That’s what she’s fuckenwell supposed to have said after he came out and the nurses carried him away, with his lopsided, dented head. ‘From now on’ she told ‘those with ears to hear’, they ‘must stop eating the tart before they get to the jam’. He doesn’t know who ‘those’ are and what tart she was talking about. All he knows is that whenever his mother talks about his birth, Treppie always sings ‘Sow the seed, oh sow the seed’, and then Pop looks the other way. Lambert reckons his mother’s not all there any more. She’s lost some of her marbles.

Pop and them used to rent a house in Fietas; that was when his mother was still a garment worker at the factory in Fordsburg. But then the factory filled up with cheap Hotnot women. They were a lot cheaper than white women, so she had to leave. A little while later, they bulldozed the kaffirnests here in Sophiatown. Pop and Treppie came to see for themselves, they say. Some houses were just pushed down with everything still inside, so all you heard was glass breaking and wood cracking. Then Community Development started building here, right on top of the kaffirs’ rubbish. Decent houses for white people. Treppie used to work for the Railways in those days, and he asked for his pension money early so he could put it down for a deposit. Like this — ‘ka-thwack’ — he always demonstrates, in Pop’s hand, ‘tied with an elastic’.

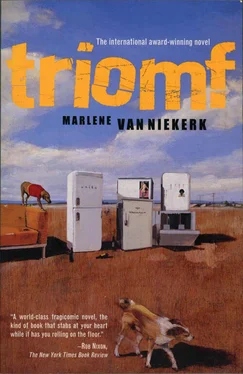

Then they started from scratch again on the fridges. Washing machines and fridges, but mostly fridges. They went and fetched them with the old Austin, stood them up in the yard at the back here, fixed them up and then took them back to their owners. And his mother took up her roses again. One thing he still remembers from Vrededorp is that he grew up around fridges and plastic buckets full of roses in the little backyard. His mother used to leave him behind, with Treppie, so she could go out and work. She says she doesn’t trust Treppie further than she can throw him, even though he is her brother, but what was she supposed to do? she always asks. She had to help bring in some money, especially when they first came to live in Triomf. Pop used to drive her up and down all night long in the Austin, to the grand hotels and bioscopes and restaurants and places. By the time they got home, it was late already, and by then Treppie was drunk as a lord. It was a real balls-up. He’s still got the marks on his backside where they say Treppie burnt him with cigarettes. ‘So he’d shuddup,’ Treppie always says about those days. Treppie says he, Lambert, was full of shit when he was small. Then he grins spitefully at his mother and Pop, and he says he wonders who Lambert really takes after. Takes after or not, he knows his worth, and he proved it by helping them out with the fridges when he got older. By the time he reached standard seven, he was head and shoulders above Pop, and he’d developed a helluva strong pair of arms. ‘Like tree trunks’ Pop used to say. He could pick up a fridge and shift it on to the back of the Austin lorry all on his own. That Austin’s long gone now. The fridges and washing machines too. That time with Guy Fawkes. The day before Guy Fawkes, when he couldn’t find his spanners in the grass. Now it’s just the old Fuchs and the old Tedelex out there in the back. Real old heavies. Treppie says they don’t make them like that any more. You can stuff a whole cow into just one of those fridges. And the washing machine from the war. The Industrial Kneff. It’s an antique, he says. When he gets pissed, he tells the story of how Hitler used to wash the Jews in the Kneffs before sending them to the camps. Whole laundries full of Kneffs, full of Jews. Clothes and all. They had to go through the whole cycle, from pre-wash to spin-dry. Treppie says Jews are dirty. Even a spotless Jew is good for one thing only, Treppie says, and that’s the gas chamber.

He’s never been able to figure out this business of the gas chamber. Must’ve been a helluva contraption.

When Treppie finishes the story, he lets out a little sigh and then he says: It’s all in the mind. And sometimes he also says: We should’ve had Hitler here, he’d have known what to do with this lot. But he doesn’t sound like he believes it himself, and then he strings together a whole lot of words that he, Lambert, can’t make head or tail of. Holocaust, caustic soda, cream soda, Auschwitz.

Treppie’s the only one who’s still got a job. At least, that’s what he says. Pop’s been on pension for ages now, and he, Lambert, gets disability, over his fingers and everything.

Treppie goes out on jobs most of the week. His mother says what work, he just sits and boozes with the Chinese in Commissioner Street. Treppie says, bullshit, he won’t touch that rotten Chinese wine. He says he’s the only expert the Chinese can afford; they’re not the richest of people, and their fridges are old. And he doesn’t always get cash from them, either. They give him take-aways or some of their old stuff. Like the video machine, which he, Lambert, fixed from scratch. Never touched something like that in his life before, and then he actually went and fixed the damn thing. With his own two hands. He looks at his hands. Then he looks at Elvis.

Elvis is reading about the seven candlesticks. He takes out a white hanky and wipes his forehead.

That’s Triomf for you. People sweat around here. The houses lie in a hollow between two ridges. On days like this it smells of tar. Tar and tyres. And if there’s a breeze, then you also smell that curry smell coming from the Industria side. Pop says it’s not curry, it’s batteries. But it’s not nearly as bad as on Bosmont ridge, where the Hotnots live. When he goes there on Saturdays, to scratch around on the rubbish dumps for wine boxes, there’s a helluva stink. It smells of piss and rotten fish. Treppie says it’s coloured pussy that smells like that. And when he, Lambert, then tells Treppie it’s all in the mind, Treppie wants to kill himself laughing. Why, he doesn’t know. Treppie’s also got a big screw loose somewhere. But it’s a different kind of screw to the one that’s loose in his mother’s head.

The chappy from the NP also wipes sweat from his forehead like that, with a neat little hanky he takes out of his blazer pocket. Five minutes of talk about the election, five minutes explaining the pamphlets and then he’s in a sweat. Last time he was talking about the pamphlet with the NP’s new flag on it. Treppie said it looked exactly like a lollipop in a coolie-shop. The sun shines on all God’s children, the bloke said, and Treppie said, hell, after all this time, the NP still thought it was God, with the sun shining out of its backside. God or no God, Pop said, he was going to miss oranje-blanje-blou a lot. How was a person supposed to rhyme on the new flag? But the NP-man’s girl, who always comes with him on his rounds, suddenly said, ‘The more colours, the more brothers!’, and then she quickly straightened the straps on her shoulders again. That silly little sun on the pamphlet, his mother said, looked more like the little suns on margarine and floor polish, if you ask her. Now she’d really hit the nail on the head, Treppie said. The little sun stood for grease , for greasing . The NP was full of tough cookies, and you had to grease a tough cookie well before you could stuff her, he said. And then he looked so hard at that girl’s tits that she got up right there and then, and walked out, dragging the NP chappy behind her.

Treppie doesn’t like visitors.

Читать дальше