She reached into her sweater pocket, withdrew the Turk’s map, in its many folds, and zipped it carefully shut within her purse alongside her phone. Dinner was just over three hours away.

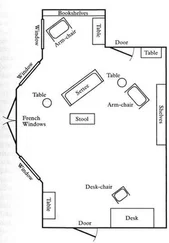

She opened the door to the salon and entered what felt like a different world, adjusting her step to fit the beat of a female singer’s smoky alto. Carefully coiffed heads turned and nodded in her direction, a chorus of bonjour s over the hum of blow-dryers and the tinkle of water running. Marco was waiting, with a shiny black smock in his hands. While an assistant hung Clare’s sweater, then placed her scarf and earrings on a black velvet tray and stowed them behind the salon counter, her hairdresser slipped one sleeve of the smock over one of her arms and, then, the other. The smock flapped and slid over her, as light as a casing of feathers. On an ordinary day, she would have smiled at the sensation, so reminiscent of Dorothy when she entered the Emerald City. But she felt a sudden chill, and shivered.

“Are you cold, Clare?” Marco asked her in French, emphasizing her first name, as though he realized he was virtually the only service-providing person in Paris who didn’t “Madame Moorhouse” her. He probably did realize. He traveled regularly to London, where the salon had a sister business, and undoubtedly spoke fine English, but they always conversed in French, to the point of pronouncing immutably English-language words in a Gallic manner: le blow-drying, le hamburger. Marco was very chic, and very discreet.

“I’m fine,” she responded, also in French.

She allowed him to lead her to a chrome-colored seat before a large gilt mirror. “As usual?” he asked, pushing a few strands back from her forehead.

Her face stared back at her, his face hovering just above hers and, beyond their two faces, the street. She felt as though she were looking at gradations of animation: her face pale, her hair pale, her expression as calm as usual, betraying none of the turmoil she’d been feeling; his face also serious and pale but his hair a brilliant reddish-black, and his eyes enflamed and searching; the world outside awash with the buoyant passage of pedestrians, the colors of spring.

Tall plane trees, vibrant with shimmering chartreuse leaves, lined the traffic island in the middle of the avenue.

She clutched the edge of her chair. The profile of a man’s body. The way he moved, just as she remembered. Lean and economic. Unpredictable. His body had never enveloped hers; instead, it had carried hers along. They’d been the same height standing face-to-face, the same length lying side by side. She turned her head to look directly through the windowpane. But there was no one on the traffic island, not even a body on which to pin a mistaken identity. She stared again at her own image in the mirror. She saw her face, her eyes, her hair. She closed her eyes, reopened them. She was still looking at her own pallid image. Everything as it should be, and yet, she’d had two sightings of Niall now, in one day, both of them so convincing. This shouldn’t still be happening to her. In the first years, decades even, she’d catch her breath and swallow her heart, sure she was catching a glimpse of him, and then the man she was looking at might turn his head and she’d see someone much older, or someone much younger, or maybe even a woman. Increasingly, however, the vision would move from her sight without her getting to view a face clearly, and she’d find herself left with the feeling that what she’d seen really had been him, even when there was no chance it could be.

She didn’t want to think about what his face would look like now, deep in the ground, inside its casket. A dry skull, maybe some dark strands of hair. All that was left when all the bark and clamor had ended. Death knew no glamour.

“As usual,” she said.

She clasped her two hands in front of her, pressing the smock down against her thighs. If she kept seeing someone who was dead, and feeling almost one hundred percent certain about it, maybe she had also dreamt up her encounter with the Turkish wrestler. Maybe she was actually hallucinating. She’d read of stranger things happening to people. A chemical imbalance. Or guilt rising up from the past to pervert her brain, like Macbeth thinking he saw Banquo, or Lady Macbeth seeing bloodstains on her clean fingers. What was insanity, anyhow? Perfectly rational people imagined enemies in their neighbors; maybe cool and collected women could start imagining encounters with murderers. Or, at the very least, dream up their resemblance to someone with whom they’d had an unsettling recent encounter. After all, bad skin and a cheap leather jacket — that could describe a good portion of the world’s population. Could she have conjured this whole connection up, just as she seemed to be conjuring up the figure of Niall on every street corner? Was the man she saw on television even the same person as the wrestler?

“Perfect,” Marco said. “Shall we wash your hair, then?”

She was glad she hadn’t bothered Edward. Really glad she hadn’t gone down to a police station. She lifted her hands and watched the bottom of the smock slither towards her calves, as she stood. Marco’s assistant led her to a washbasin, and she allowed her head to be tilted back, her neck to be slotted into cool porcelain. Water began to pour over her skull, filling her ears with warm, soft liquid.

There were many dark-complected heavyset men with skin ruined by steroid consumption. Why shouldn’t there even be more than one with a droopy eyelid? How carefully had she really looked at him? She’d avoided his eyes at first and then they’d walked down the street side by side. It’s not as though they’d sat at a table across from each other. Just imagine if she’d gone in to defend the guy, they brought him for questioning anyhow, and it wasn’t even the same person. Not only would she have jeopardized tonight’s dinner for nothing, people would laugh at her. And then they might start saying she was crazy. Or had lied on purpose because she sympathized with the assassin’s cause. This was how it was nowadays — disagreeing with the authoritative majority was tantamount to being subversive, especially when related in any way to terrorism. When Jamie had bought a T-shirt condemning the war in Iraq, Edward had asked him not to wear it. “Not to school, at least,” Edward had said. “I know you do not mean it this way, and I completely agree with your right to disagree. But there are some people out there who will say it means you are supporting Al Qaeda.”

Of course Jamie had worn the shirt anyway. From the youngest age, Jamie had bucked against anything he perceived as unjust. In kindergarten already, he’d come home with a bite on his arm for defending his snack against a bully. When President Bush had threatened to invade Iraq, he’d insisted on joining the throngs of protestors in the streets of Paris. He’d even begun interrogating a dinner guest from the American embassy one evening, until Edward had intervened. That had been embarrassing. But Jamie was young. Younger people were more quickly forgiven their opinions and the actions they took based upon them — until they came back to haunt them. The police had said the man in the photo belonged to an extremist organization, but they hadn’t said when. Maybe he was just a poor devil who had gotten himself caught up in more than he intended when still a kid — signed a petition written by an old school friend, attended a meeting or two run by a neighbor, and ended up with his name on a mailing list for the wrong organization, all back when he was an ardent innocent college student. Or a young man trying out his first job. Maybe he was just an ordinary fellow who’d made one very big mistake that would now follow him around forever, at the urging of a friend, or family member, or a lover. If he was apprehended and his case went to trial, this one mistake from his past would be his undoing.

Читать дальше