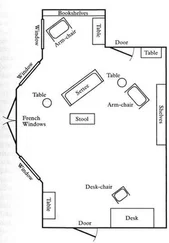

She pushed open the door to Jamie’s room. There was his duffel still on the floor, inked up with phone numbers and names. On top of his desk lay a jumble of flyers. She tapped the papers into a neat pile without reading what they announced and put them back on the desk. Here’s how she’d handle it. She’d phone Edward around 6:00 p.m., before he headed for cocktails at the embassy, to explain there’d been some new trouble in school, and she wanted Jamie to come home for the weekend. She’d claim she was the one who’d made the decision. She wouldn’t specify when Jamie was scheduled to arrive, and Edward wouldn’t ask — he had other things to think about. Then, if Jamie did come back during dinner, Edward wouldn’t be startled to see him, although he might feel frustrated. Edward didn’t fall apart; Edward compartmentalized. In the morning, he would ask, “So, what is going on with Jamie now?” They would go in together to wake Jamie and speak with him briefly but somberly before Edward headed in to his office. When Edward heard that Jamie had been caught cheating again, he would tell him he was sorry Jamie felt he had to keep doing this, but he had no choice but to take his punishment. They would not ask about nor listen to any claims regarding anyone else’s involvement; Edward would insist whatever anyone else had done was irrelevant. And they would not discuss Jamie’s unauthorized flight. This last could remain between her and Jamie, something for her to deal with separately and in confidence.

“I do clean linen, Madame?”

Amélie stood behind her, viewing the duffel bag. It lay there in the center of the room like an enormous telegram, heralding the arrival of its owner. In one hand, Amélie held a duster. In the other, the phone. She held it out.

Was it Jamie?

“Madame Gibson,” Amélie said.

Clare took the phone, cupping her hand over the mouthpiece. “Draw the curtains and open a window. But no need to change the sheets. They’re clean, aren’t they?”

“Oui, Madame.” They left unspoken the fact that enough time hadn’t elapsed since Jamie’s last visit for the sheets to have grown musty. Clare would miss Amélie when they went to Dublin, for the opposite reason she would miss Mathilde. Mathilde kept the household on its toes, and life interesting. Amélie was safe. She was kind also. Never grow too close to the staff was one of the first rules of diplomat living but when they were the people who knew her family’s secrets, when they were the people she saw day in and day out, the people she sometimes saw more often than her husband, substitutes for the spinster aunt or longtime neighbor or friend from grade school or widowed grandma, becoming attached to them was difficult to avoid.

In Dublin, there would be a whole new set of staff members to get to know, then have to say good-bye to. If they went to Dublin. There was tonight’s dinner still to get through. Plus Edward knew of other rumored candidates for British ambassador to Ireland.

“But none,” he had pointed out this morning, as they dressed, “is married to a girl named Fennelly. If nothing else, that should prove my commitment to continued good relations between the Crown and Ireland. You are my trump card, Clare. As always.”

“You mean continued domination,” she, at that moment crouched down giving a last-minute buff to one of his shoes, had said.

“I mean continued subjugation,” he’d answered, reaching over her for the violet tie she’d given him for his last birthday, which they both knew he hated, and looping it around his neck. She’d stood up to knot it for him. Then she’d turned her back, and he’d closed the clasp on her necklace, his warm fingers brushing her neck. That might have been the real moment she’d committed herself to getting him Dublin.

“Hello, Sally,” Clare said into the phone.

Sally Gibson’s son, Emil, had played soccer with Peter at the International School during their first posting in Paris. She and Sally had ended up manning many a soft-drink stand together and chaperoning numerous bus trips. Ever since their return to France, Sally had been after Clare to help with every committee she herself got involved with. Her latest was the Paris chapter of Democrats Abroad.

“I’m sorry, Sally, I really can’t join,” she said. Sally was a very nice person, and much too smart to be nothing more than a soccer mom in Paris, but she had the habit of acting like a dog with a bone when she got her mind set on something — maybe because she was too smart a woman to be simply a soccer mom in Paris. She and Clare had had this same exchange enough times already; Clare might have to tell Amélie to say she was out next time Sally called. “Never mind my own personal inclinations, which I’ve already told you are zero when it comes to politics, for me to join wouldn’t be right. The Foreign Office is devoutly apolitical, and expects its personnel, and their families, to be that way in public also.”

She checked her watch. 2:55 p.m. She’d lost too much time on all this other stuff already.

“Everyone is political, Clare. Especially in these days. You can’t avoid it.”

“Well, I am not.”

“You’re holding out on me. I know where your loyalties lie. And, Clare, this is important. We’re heading towards disaster. The sanity and safety of our entire globe could depend on this.”

Clare sighed. “Listen, Sally, I just can’t. I’m sorry. But are you running something for the school kermesse this year? Maybe there’s something I could do for that, even though both the boys are gone now. Maybe Mathilde can send over a couple cakes.” That sounded bad. She added, “I mean, maybe we could still contribute something.”

After she hung up, she headed down the hall towards the kitchen. She hoped Sally wouldn’t go talking behind her back, saying she was starting to act snobbish. People forgot — or maybe never knew in the first place — that none of the pomp and circumstance that surrounded a diplomatic family’s daily life actually belonged to them. The splendor belonged to the Crown; she and Edward were just staff (and she unpaid staff, at that). If anything, she and Edward belonged to the Residence more than it belonged to them. Not only would they pack up their things when Edward’s job in Paris was finished and move on as though from a hotel, she didn’t have much say about life within the Residence now.

“Attention!” Mathilde hissed before Clare managed to clear the kitchen doorway. She pointed a finger towards the oven then raised it to her lips.

“Is there a baby sleeping?” Clare said and immediately regretted her flippancy. She lifted the cloth covering the asparagus to check that the stalks hadn’t begun to yellow. They lay there like a mass of entwined lovers, lovely shades of white and purple. “They’re nice, aren’t they?”

“Hah, hah, très amusant, Mrs. Moorhouse, but un bon gâteau is as delicate as a baby.” Mathilde swiped the platter of asparagus from under Clare’s eyes and whisked it over to the sink. She ran water from the tap until she was satisfied at its chill, collected a few drops on her naked fingertips, and shook them over the stalks as though she were a priest anointing them. “Tastes better, though.”

“How do you know that, Mathilde?”

Mathilde laughed, not with her usual loud bark — so as not to disturb the cakes — but in a sort of silent version of it, hacking at the air. “A little backjaw from the minister’s wife, nae? A little cheeky? You feeling yourself, Mrs. Moorhouse?”

Despite her determination not to think about him anymore, the image of the wrestler’s shiny forehead rose in her mind. Clare looped a strand of hair behind an ear and crossed her arms across her chest. “ Can an employer be cheeky to an employee, Mathilde?”

Читать дальше