Mathilde wiped her damp fingers on the apron covering her broad chest and straightened the kerchief she wore over her graying hair. Then, gathering herself up as high as her diminutive height would allow her, especially when confronted with Clare at well over half a foot taller, she answered, “Anyone can be ill mannered. Even Monsieur le Président to a street cleaner.”

She looked fierce, and Clare remembered what Edward had said: We don’t need the wrath of Mathilde tonight. Besides, Mathilde was right. Everyone deserved respect. Even if that hadn’t been what Clare had been asking, and Mathilde knew it.

“You’re right.” She left the asparagus and peered into the fridge. The strawberries had been impounded. She shut the door. “Although, somehow I can’t imagine a French president chatting up a garbage collector.”

Mathilde snorted. “Neither can I. The French wouldn’t have it. So, I’ll be putting an orange Bundt into the oven tomorrow, n’est-ce pas? ”

Orange Bundt cake was Jamie’s favorite. This was Mathilde’s way of making peace, at the same time as keeping the upper hand; tendering both a spontaneous offer to please Jamie and evidence of her awareness of his mid-school-week arrival. She probably also thought Jamie had eaten the strawberries. Well, good. Let her. She would forgive Jamie for it more easily than if the thief were she or Edward.

“That would be lovely, Mathilde.”

Two large tubs of plain yogurt stood on the counter, like country cisterns, white and thick.

“My wife, very good cooker,” the Turk had said, “She make very good yogurt, very good for body.”

If they were in America, this wouldn’t be true for him once they brought him in, no matter whether his wife was allowed to send him yogurt. If caught and convicted, the Turk could be sentenced to death. Hard to imagine of the man she’d walked down the street with just a couple of hours earlier, listening to him praise his wife’s cooking. Clare felt a pain in her chest, the wind knocked out of her. But no, capital punishment didn’t exist in Europe, neither in France nor Turkey. Only Americans, amongst the Western nations, clung to killing their killers.

That’s nuts, she thought. I’m feeling sorry for this man? He’s a terrorist.

He’d stepped out in front of her, holding a piece of paper in his hand, pressing it on her. But, back then, he’d been just some poor lost guy, sweating in a cheap leather jacket. How could that same man be an assassin?

There must be a mistake, she thought. Her mistake. There was an eyewitness.

“If you will be tearing your hair out, Mrs. Moorhouse, I’d ask you don’t do it around my cooking,” Mathilde said, pulling a tray of fish out of a fridge, where it had been marinating.

Clare dropped the wisp of hair she’d yanked from her skull, without realizing it, into the garbage. She noticed the clock on the oven door, which used the international standard notation: 15.25. Her appointment at the hairdresser was at 4:00 p.m. “What’s the yogurt for?”

“The dessert,” Mathilde said. She plopped the fish down on the counter, suddenly heedless of the cakes in the oven. “Along with the strawberries.”

Time to leave, Clare thought.

“What’s left of them, anyway,” Mathilde called after her.

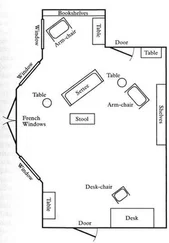

Before going out, Clare slipped back into the study and turned on the television. But it was before the hour: no headline news. She flipped to CNN. Sports coverage. She flipped to BBC. A world business report.

She had arranged for a car to take her to the hairdresser’s; unless there was a demonstration clogging the streets, she had time to do a quick check on Google. She sat down at the desk and tapped the space button to close the screensaver. While she waited, she burrowed her hands in her sweater pockets, the triple-ply cashmere warm and soft against her fingers. She felt the cold crepe of thin paper and pulled a sheet out, not her to-do list, nor the Turk’s map, but the forgotten flower shop receipt. She’d failed to enter the sum into the day’s expense sheet.

She reached for the drawer containing the Residence’s expense ledger, but before opening it, she tapped a few words into Google. Then, as the site loaded, she trained her eyes over the receipt. Jean-Benoît wrote with a strange angular tilt, and his notation was as meticulous as his lettering. Instead of scrawling out the ultimate price, after calculating the fifteen percent embassy reduction, he’d begun at the beginning, marking down the precise number and regular cost of each element of each bouquet— lys jaunes/48 tiges/6,50 euros/312,00 euros —followed by the price adjustment. Even the exact time of purchase was specified: 10.12.

Clare glanced up at the computer screen, fixed now into a crossword of calibrated print and graphics.

His face was still there, his same droopy eyelid, his cheap jacket. She couldn’t have been mistaken. Her wrestler was wanted for shooting a French parliamentarian in front of Versailles at 10.30 this morning.

But that was not possible.

She checked Jean-Benoît’s receipt. There it was at the bottom.

Time of purchase: 10.12.

He’d crossed the street and almost been hit by a car. She’d waited to see he reached the other side safely and then waited to be sure he wouldn’t turn back. She’d seen his wide, dark form lumber down the Rue Saint-Placide, until he’d become just another urban spot amongst many. And then she’d glanced at her own watch.

10:29 a.m.

Her watch had read 10:29 a.m., and she’d calculated in her mind how much time she had left to finish her shopping and also stop at the pharmacy to pick up some homeopathic medicine for Mathilde before they arrived with the plate back at the apartment.

Clare looked at her watch now. The gold around its face twinkled up at her in the light reflected off the computer. 3:41 p.m. She checked the clock in the far right bottom of the computer. Also 3:41 p.m.

She picked up the desk phone and dialed. A sensible male voice: quinze heures, quarante-et-un minutes, trente secondes. She waited. Quinze heures, quarante-et-un minutes, quarante secondes.

She looked back at her watch. Even the second hand was accurate.

There was no way her Turk could have gotten to Versailles in one minute. Not even if he’d sprouted wings and flown. Versailles lay fifteen miles southwest of Paris.

Clare touched her spidery fingers to her forehead. She was careful not to groan or sigh, or make any sound the staff might hear.

She reached for the phone, but her hand stopped before dialing a number. She sat there for a minute, feeling the press of time, both past and present, on her. Then she laid the phone back down on its cradle. She still wasn’t going to call anyone — not the police, not Edward. Not until she’d thought this over. Never do anything impetuously. Never do anything without thinking through all the repercussions. She’d made that mistake once. She would not repeat it.

Her situation was complicated.

If she was wrong — although how she could be, she didn’t see at present — and provided this man with an alibi, she could be abetting an assassin. A man would have been murdered, his murderer would come away scot-free, and she’d be responsible.

If she was right about the timing but some other detail was wrong — maybe the wrong time had been reported to the news stations, either by mistake or on purpose for some tactical reason — the police wouldn’t take her support of his innocence seriously. She wouldn’t become responsible for freeing a murderer — but she might come under scrutiny herself. What’s this woman doing, not Turkish, not involved in this case, the Irish-American wife of a British diplomat, getting involved in this case? Defending a presumed political assassin? At best, this would be uncomfortable for Edward, particularly at such a sensitive professional moment. At the worst…

Читать дальше