“Never mind,” she said. “It’s nothing. I’ll wear the beige. And the emerald.”

She replaced the phone and took out her list. The emerald was her most tangible link to Ireland. The ring everyone wanted; the ring she wore as seldom as possible because it meant too many things to her. Her wealthy Irish grandfather had used it to woo Mormor — a platinum claddagh with a spectacular 5.5-carat emerald and two enclosing diamonds.

“Why did she leave the emerald to Clare?” her sister-in-law, Amy, had asked at the luncheon after the reading of Mormor’s will. “She could just as well have given it to Rachel.”

Clare had been upstairs changing Peter’s diaper in the guest room bathroom, directly above the kitchen. She’d heard the whole conversation through the grating. Rachel was the firstborn of the next generation, Clare’s brother Luke and Amy’s daughter, then five years old.

Her other brother, Aidan, who wasn’t married back then and still wasn’t married now but was always very mindful of the politics of family order, had said, “Probably she figured there’d be more granddaughters to follow. She didn’t want to seed any future jealousies amongst them.”

“Or to the estate. She could have left it to the estate. That would have been the normal thing to do. The estate sells it and divides the proceeds equally amongst the heirs,” Luke had said.

Silence had wafted up the vent. A metal door had gone clunk — the oven.

“Because,” her mother had said, “Clare’s got those hands.”

“What about her hands?” her sister-in-law had squeaked.

“Haven’t you ever noticed them?”

Clare had thrown a towel down over the duct so she couldn’t hear the rest of the conversation. No one other than Niall had ever mentioned her hands. She didn’t know why if her mother had noticed them, she’d never said anything about them. Mormor neither. She’d looked down at them, water spilling over them, and wanted to clothe them. It had taken her a long time after that to get over her feeling of nakedness about them.

Clare stared at her hands, now slightly veined, the skin just beginning to thin on them — these hands that had gotten her into so much trouble. Then she picked up her pen and across the bottom of her pad, wrote, “Clean emerald.”

She shoved the pad away. She would make a few necessary phone calls, complete this week’s expense report, then head out to the hairdresser’s. Was Mathilde back from lunch? Did she dare go check up on her? Only Mathilde could manage still to inspire fear after all else Clare was facing. If only Mathilde had become a nursemaid instead of a chef. She would have sorted Jamie out in a way Clare never was able.

Yet again Clare pulled the BlackBerry from her pocket. Nothing. Even as he became in many ways more dependent upon her, Jamie was spiraling further out of control. He would falsify a message from her and jump on a plane without any adult’s knowledge, much less permission. He would come and go when he wanted, and explain himself only when he was good and ready. What did she know about what had really happened? She’d told Barrow she’d call them rather than the opposite; she had to try now to put this conversation off until she’d managed to rein Jamie in enough to find out why he’d done what he’d done.

And she wasn’t going to talk at all, to anyone, about this latest strange encounter, with the Turkish stranger. She’d file it away amongst the other experiences in her life she didn’t intend to reveal to anyone.

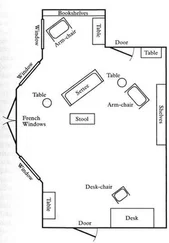

Clare closed the door to the study softly behind her as she stepped into the hall, and paused to listen. There was no sound coming from the kitchen. Either Mathilde wasn’t back yet or she was back but wasn’t unhappy.

She headed down the hall towards the bedrooms. She’d check just once, on the off chance Jamie had snuck back into the Residence while she was in the study with the door closed, as quietly as he’d snuck out while she was having lunch with his father.

She stopped at Peter’s door first. Maybe it would be a better place for hiding. Or maybe Jamie’d looked for inspiration in the way his careful older brother differed from him, so apparent even in the state of his bedroom. When Peter had left for Fettes, he’d folded every article of clothing he wasn’t taking with him, sorted them by season, and placed them in separate drawers in his room. He’d cleared his desk of all paraphernalia, tossing into the garbage anything less than vital, and organizing whatever was left into boxes that he labeled and lined up along the top shelf of his room’s armoire. Looking around, the week after she had returned from delivering him to Scotland — not to snoop, but to check whether he’d left anything important behind — Clare had been struck by how similar the interiors of his desk drawers now appeared to those in finer hotels. A few neatly piled notepads, a handful of sharpened pencils and capped pens, the leather-backed Bible he’d received from his American grandparents for his first Communion, a box of throat lozenges, and a flashlight. Only a teenager like Peter would leave a room like that. “I am in control,” the room said. “I don’t require — or wish — anyone else’s help to keep my life in order.”

Peter’s room looked as clean and organized — and empty — as ever.

She shut the door again.

When Jamie had banged out of his room for the last time before heading off for boarding school last fall, he’d left dirty pajamas in a tangle on top of his bed and an explosion of books shooting out from under it, along with a few unmatched socks, a half-drunk bottle of water, and a bent ruler. Opening the door to peek in upon returning from dropping him off in London, Clare had almost been able to believe Jamie had gone just for the night, for a sleepover at a friend’s, and would be back in the morning. In some way, the casual mess he’d left behind had made Clare feel better.

“Do you think it made Jamie feel better, too, a way of pretending he wasn’t actually leaving?” she’d said to Edward over their third or fourth solitary dinner together. Of course, she and Edward didn’t usually dine as a duo; most nights brought some sort of engagement, or else Edward might be traveling.

“Oh, it’s James, that’s all,” Edward had said. “Not the most orderly boy, is he?”

Clare had cut her veal cutlet, releasing a trickle of blood towards her potatoes. Pink had swirled into white, laced the taupe edges of mushroom sauce. “He’s not used to having no one around to care for him.”

“All the more reason for him to start learning,” Edward had said, reaching for his water glass. He was compelled to consume so much alcohol during work-related lunches and cocktail parties and dinners that he stuck to water when it was just the two of them. “And he will. I wouldn’t worry. Not about Jamie’s housekeeping, I mean.”

“I won’t. I’ll let his roommate do that,” she’d said, and they’d both laughed. “Can you imagine?”

She’d never mentioned Jamie’s empty room to Edward again. Increasingly, she and Edward avoided the topic of Jamie altogether, other than the inescapable, such as any report that had been sent home from Barrow. Edward had suggested early on that it wasn’t helpful to Jamie to be able to return home from Barrow whenever and as often as he wanted — it wouldn’t aid him in adapting to becoming more independent. Having made clear his thoughts on the subject once, he was not one to harp. She persisted in allowing Jamie to return as often as he wished anyhow, and Edward greeted him on each visit with affection and no outward hint of disapprobation. She knew Edward called Jamie from the office once a week to chat, too, and she supposed Edward had figured out that Jamie called her nearly every evening. But she and Edward never discussed the contents of their separate phone calls with each other, any more than they returned to the subject of Jamie’s lack of self-sufficiency, except when she had something very specific to relate. And even then, sometimes she didn’t. Instead, they talked about Peter’s college search or where they should take their annual summer holiday as a family.

Читать дальше