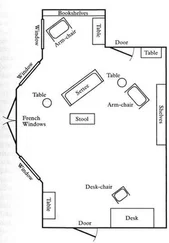

Clare followed the assistant, one hand clasping the two ends of the fresh towel, the other her purse. There was noise, the sounds of pop music and hair dryers and people chatting. She slipped into a chair and set her purse down by her feet. She looked into the mirror.

“Come on.”

The car doors made a click as they opened. They walked single file, he in front, until they reached a gentle clearing, off the forest road but within sight of the car. He settled down amongst the grass and pine needles and drank from the bottle. She sank down beside him. He offered her the bottle, and she shook her head. He put an arm around her and pulled her onto her back. They lay there, under the pines and oaks and maples and dying elms, their uppermost branches scattered with yellow leaves that gleamed in the moonlight, in silence except for the sound made by the bottle when he tipped it backwards.

“You like it here,” he said, more an acknowledgment than a question.

“Yes.”

“You’re always sittin’ in the garden, or puttin’ flowers on the table.”

He placed a hand on her hip, and she felt as though they were carbon copies, side by side, their breath rising and falling together.

“You ever have the feeling there’s something you fancy saying, but no with words?”

That was exactly how she felt, had felt, almost every day of her life.

In that pale light, she fell asleep. She woke at dawn, startled by a shaft of sunlight breaking through the tree boughs. He was already awake, staring up at the tip of morning. He got up and kicked the empty bottle of Jameson into the brush with the toe of his boot. Before following him back down the path, she stooped to retrieve it.

She only meant to keep him from littering, but it took her a long time to part with the bottle. After they got back to the house, he disappearing into his bedroom to sleep through the rest of the morning, she went into her bathroom and rinsed it out. Once everyone else in the house had gotten up, she filled the bottle with wildflowers and set it on her little bedside table. The bottle stayed there through the rest of her stay at her aunt and uncle’s. It followed her to her new room in Cambridge. Until the day she returned from Dublin.

“Café? Un jus d’orange?” The assistant laid a new dry towel around her shoulders and pinned it together with a large silver hair clip.

“Oui, merci. Un café.”

Marco appeared, armed with a comb in his right hand and an enormous blow dryer in the other. He was a terse man, a quality Clare appreciated in a hairdresser. With Marco, she didn’t feel required to make conversation over the roar of a hair dryer. That alone was enough to make her a loyal customer.

They exchanged a few civilities, always in French, as he ran through her hair with the comb.

“Les enfants vont bien?” he asked.

“Oui, très bien. Il fait beau aujourd’hui, n’est-ce pas?”

He nodded. “Il va faire chaud en juin.”

When her hair was smooth, parted, and combed forward towards her brow, the conversation stopped. He dropped the comb into a net and enveloped her head in a cloud of hair spray. From an array of hair utensils, he selected a long and thin round brush and switched on the blow-dryer, applying all his attention now to the task of making her hair flip back from her face.

The assistant returned with her coffee, and Marco waited, blow-dryer in hand, like a gun cocked and ready to go, while she took a sip. She laid the cup back down on its saucer. Black coffee, cola, and beer. That summer, she’d watched Niall gulp down gallons of all three. But, though she kept the empty bottle from that night by her bedside, she never again saw him drink Irish whiskey. The next time she could remember seeing anyone drinking Jameson whiskey was the first time she met Edward, three years after Niall’s disappearance, three years since another man had managed to arrest her attention.

The man from the British Consulate—“Hello, my name is Edward Moorhouse,” extending a hand in her direction when she’d walked into the restaurant — waited for her to pick up her ginger ale. His fingers were smooth and full on his glass of whiskey, and one bore a heavy gold ring embossed with a crest. Niall would have spat at such a ring, but she’d promised herself not to think about what Niall would think ever.

“Ireland,” the man said to her father, “gives us so much that is lovely. Even the names.” He took a sip, placed the glass back down on the pale damask tablecloth, and smiled at her. “May I ask whether you have a second name, Clare?”

“Clare Siobhan,” she said blandly. It was on the tip of her tongue to add: “But I’m American, not Irish.” But she didn’t.

“Clare Siobhan,” he’d repeated after her, thoughtfully.

“Clare Siobhan Fennelly,” her father said, with a bit of a lilt and smiling at her. She smiled back at him. She was home visiting for a long weekend, and he’d asked her to join them for lunch straightaway when he’d picked her up at the Hartford train station the evening before: “Kennedy and I are going to the Coach House tomorrow with some British guy, Edward Moorhouse, up from Washington, like you. It’s bound to be a bit dull but the food’s good.” She’d agreed, mostly because she didn’t know how not to without displeasing her father. At least if the guy was British, no one would be trying to fix her up with him — she was growing weary of her parents’ not especially subtle efforts to find her a husband, or at least a boyfriend. “Are you sure?” her mother had asked when she’d called to say she had Thursday and Friday free and would come up to Connecticut. “Isn’t there anyone down in Washington you’d like to spend your days off with?”

How could she explain that, no, there was no one she wanted to spend her days and especially her nights with, how the idea of being with another man had come to seem ridiculous to her after Niall? They knew nothing of her and Niall.

“This man Moorhouse wants to talk to us about investing in Northern Ireland,” her father had continued as they’d driven along the familiar streets home from the station. Barry Kennedy and her dad were on the board of a company with considerable interests in both London and Edinburgh. “That’s what he does, goes around the States trying to get U.S. companies to invest, despite the MacBride Principles. You know the MacBride Principles?” Clare had shaken her head, although she had heard talk of them, so her father had explained how a movement towards legislation was growing, newly backed by the Nobel Peace Prize winner Sean MacBride, to discourage U.S. companies from investing in Northern Ireland on the basis that employment policies there were prejudiced against Catholics. She’d listened with half an ear, never wanting to hear a word again about the Troubles and having understood the essential: she was definitely safe from any awkward attempts at matchmaking. No way would her dad be hoping to fix her up with this guy. Not if this Mr. Moorhouse was trying to convince them to invest in British interests in Northern Ireland.

Still, when she’d seen the visitor from the British embassy waiting for them in the Coach House restaurant in his well-buffed black shoes, she couldn’t help but feel bad for him; he looked so decent. A nice-looking man in a smooth, well-kept way, tall, solidly built, and fair, with calm, thoughtful eyes. A part of her wanted to warn him. She knew full well how her father and Kennedy were going to respond to any overtures regarding investment in Northern Ireland. Clare’s father was as strong a believer in Ireland for the Irish as the next Irish-American, even if he professed to oppose the current Provisional I.R.A.’s more radical methods. She wouldn’t want to ask where Kennedy stood on the subject.

Читать дальше