Manuel Rivas - The Low Voices

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Manuel Rivas - The Low Voices» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Harvill Secker, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Low Voices

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harvill Secker

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Low Voices: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Low Voices»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A brilliant coming-of-age novel from one of Spain’s greatest storytellers,

is a humorous and philosophical take on memory, belonging, and the nature of storytelling itself.

The Low Voices — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Low Voices», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

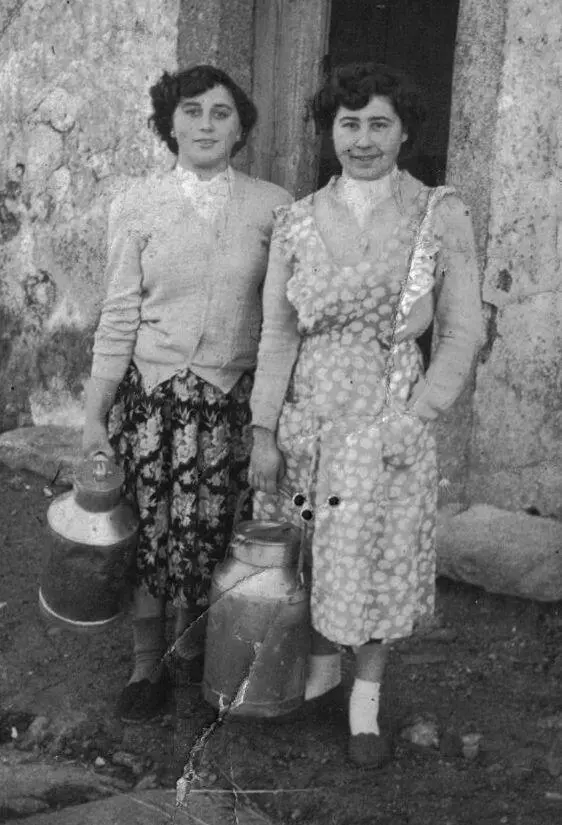

The author’s mother (on the left) and Aunt Paquita

It might be said that at this point my mother was wearing her stream of consciousness on her sleeve. She was an open body. She was talking. And others were talking through her. Who were they? In Waiting for Godot , there’s a scene in which Vladimir and Estragon hear the low voices of the dead. They make a noise like wings. Like leaves. Like sand. They whisper. They rustle. They murmur.

VLADIMIR: To be dead is not enough for them.

ESTRAGON: It is not sufficient.

No, it is not sufficient. Why does Juan Preciado return to Comala? His mother makes him promise, that’s true, in order to reclaim the inheritance of his father, Pedro Páramo. But what is that inheritance in reality? His mother describes the place where she is sending her son like this: ‘The air changes the colour of things there. And life whirrs by as quiet as a murmur … the pure murmuring of life.’ Comala may be desolate, but it is not a non-place. On the contrary, it is the place of humanity, as in Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’ there is the room of humanity. The place where being dead — or alive! — is not sufficient.

We don’t really know what literature is, but we can detect its mouth. Not only in books, but in life as well. This mouth rarely warns us it is going to open. It takes the form of a rumour. A murmur. It can even be closed, covered in earth, wounded, feeling how the words swarm excitedly around it. It can be a mouth that is contorted, painted, voluptuous, dehydrated. It can be scandalous, incontinent, enigmatic, impudent, stuttering. What it doesn’t want is to dominate. It is always an eccentric mouth. Alone or in a group, it talks to itself. Its inner movement is that of the dance in which the bodies of words contract or expand while turning. The mouth murmurs Rosalía’s poem:

Of those footsteps

That they dance now,

Forward and back,

From back to fore.

Years ago, a friend from Soneira Valley, Roberto Mouzo, an enthusiast of signs in the manuscript of earth, handed me a series of paper reproductions of the petroglyphs on the Death Coast, where there were lots of concentric circles grouped together. These drawings remained on my desk for a long time, turning invisibly around me. One day, I had to fill out one of those questionnaires about the limits of fiction and truth, invention and memory … I was both sorry for replying and unhappy with my answers. But the concentric circles were there. Whatever they might mean for experts, for archaeolatry , they murmured a response about reality and the way to view it. Reality turned out to be just one of the circles of reality. What a ridiculous piece of reality is seen by those who confuse it with sticky topicality. The optics of enlargement shown by the circles include the inner and outer senses, memory and imagination. In The Disasters of War , Goya has a title: ‘One Can’t Look’. From when we were little, the slogan of fear: ‘One Can’t Say’. Or: ‘That’s a sin’.

The mouth said what couldn’t be said. It sounded like a sin.

The departure point for the expansion of the petroglyph is shaped like the mouth that talks to itself. There it was, fermenting, on tenterhooks, both discovering and creating secrets. The petroglyph of concentric circles took me to an unusual, unpredictable place above time, like the overgrown track to A Cavaxe. To the beginning of the ‘Second Manifesto of Surrealism’: ‘Everything leads to the belief that there exists a certain point of the mind at which life and death, the real and the imaginary, the past and the future, the communicable and the incommunicable, the high and the low, are not perceived as contradictions. It would be vain to attribute to surrealism any other motive than the hope of determining this point.’

The energy source that drives this hope is the insufficient. The simultaneous walking of desire and pain. Like Charlie Chaplin the Tramp, it rests on both of these. The first films we saw were in the Hercules Cinema, in Monte Alto. All of us waiting expectantly in the dark chamber. The whole cinema mimicking the roar of the Metro lion like a liberation. But, before that, we had a logo of our own: the lighthouse casting a beam across the screen that was met with enthusiastic applause. I was very small. From those films, the only images that wash up are those of Tarzan and Charlie Chaplin the Tramp. Down Torre Street, María walked like Chaplin when she was little. This way of walking activates the mouth of imagination and memory. I became acquainted with that mouth very quickly. But I didn’t know it had inspired the enigmatic drawing of the concentric circles or been described in the ‘Second Manifesto of Surrealism’.

At the time, it was nothing more or less than the mouth of my mother talking to herself.

18. The Glazier and Long Night

THE FIRST BOOK to enter our house that wasn’t a schoolbook was a monumental work. Judging by the title, Five Thousand Years of History , by the size and thickness, a real stone slab. One of those works that leave an immortal mark on your head if they land on top of you. My mother bought it in the La Poesía bookshop on Santo André Street. We went down to the city with her and carried that book between us, as if on a platform in procession. Five thousand years of history on the back of humankind. My word, it was heavy! We carried it with a mixture of respect and glee. In particular because of the circumstances in which it was purchased. It was the feast of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, the Virgin of the Sea. We wanted to buy her a gift. Typical presents for mothers were household items. In reality, they weren’t for them. They acted as intermediaries. We were thinking of buying her a coffee machine or something like that. And that was when she took us to La Poesía and said, ‘Actually, no. This time, we’re going to buy a book.’

As a girl, my mother had been a contented, clandestine reader. She knew verses by Rosalía de Castro off by heart, even though her favourite poem, the one that trembled on her lips, was the funeral oration Curros Enríquez dedicated to the author of New Leaves , one of the harshest secular psalms in the history of Galicia: ‘Ah, of those that wear on their forehead a star! / Ah, of those that wear on their lips a song!’ A poem that sums up all this history like the plot of a detective story in which the person who embodied Galicia the best (a contemporary Mother Earth goddess) is devoured by her contemporaries: ‘The muse of the peoples / that I saw go by, / she was food for the wolves, / consumed she did die … / Of her the bones are / that with you will belong.’ We are still living one of the chapters of that nightmare, with the deceased, like Castelao, held under ecclesiastical lock and key in a Pantheon of Illustrious Galicians that isn’t even public heritage. Her beyond should be Adina Cemetery, the one she sang about, and Castelao’s should be the homeland of exile, La Chacarita, the cemetery with the most bird’s nests in the world.

Carme, my mother, had read a lot as a child. Most of all, she’d read the lives of saints. Volumes of exemplary lives that dozed in the darkness of the attic in the vicarage in Corpo Santo. The vicar’s niece, Dona Isabel, grew fond of the girl and semi-adopted her. The large Barrós brood had been left without a mother. This Dona Isabel was very special. A suitor had presented her with a parrot, which she baptised Pio Nono and taught Latin. But the Vaticanist parrot, whose cage was on the balcony, soon switched language when it heard the pine-cone collectors from Altamira passing by. It was a fan of the vox populi and quickly learned how to swear magnificently. That was until Dona Isabel ordered it to be confined to the attic, where Pio Nono, deprived of speech — a low voice — gazed at the reading girl. My mother, apart from laughing with the parrot, made the most of Dona Isabel’s patronage to disappear to the attic, where, alone with books, she would lose all notion of time.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Low Voices»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Low Voices» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Low Voices» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.