Manuel Rivas - The Low Voices

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Manuel Rivas - The Low Voices» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Harvill Secker, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Low Voices

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harvill Secker

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Low Voices: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Low Voices»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A brilliant coming-of-age novel from one of Spain’s greatest storytellers,

is a humorous and philosophical take on memory, belonging, and the nature of storytelling itself.

The Low Voices — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Low Voices», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The teacher had a stick he used as a pointer for the blackboard and maps. But sometimes, when the man became consumed by anger, the stick would turn into a primitive, terrible weapon. I remember the day he laid into one of the boys, Rafael, who was a little younger than me. The boy suddenly wriggled free, let rip a fearful howl and legged it out of the classroom. At this point, the teacher, with his staff of office, announced, ‘After him! And, when you’ve got him, bring him back here!’

So it was we went after Rafael like a pack of hounds. He was lucky he was as fleet-footed as a hare. But our pursuit was relentless, following the master’s orders. I understood that day there is no greater pleasure for a human than hunting down another human. But something unexpected happened. When we were far away from the school and the teacher could no longer see us, a dissident emerged from the pack of pursuers, stretched out his arms and stopped us. It was Xoán, the giant of the school. He had previously broken a leg. He’d fallen off a wall, and a rock had landed on top of him. He went to hospital and, when he came back, he was twice as big. Apparently, they’d tried out a vitamin complex on him. We all wanted to break a leg after that, so we could receive these extraordinary vitamins. But Xoán did not abuse his power. He was a good classmate. His fist now panned across our faces. And he said, ‘Anyone who touches the boy will get a beating that will land him at the gates of hell!’ Or something like that. A biblical mouth. A biblical fist as well. The feeling one had come face to face, in body and soul, with the beginning of all things.

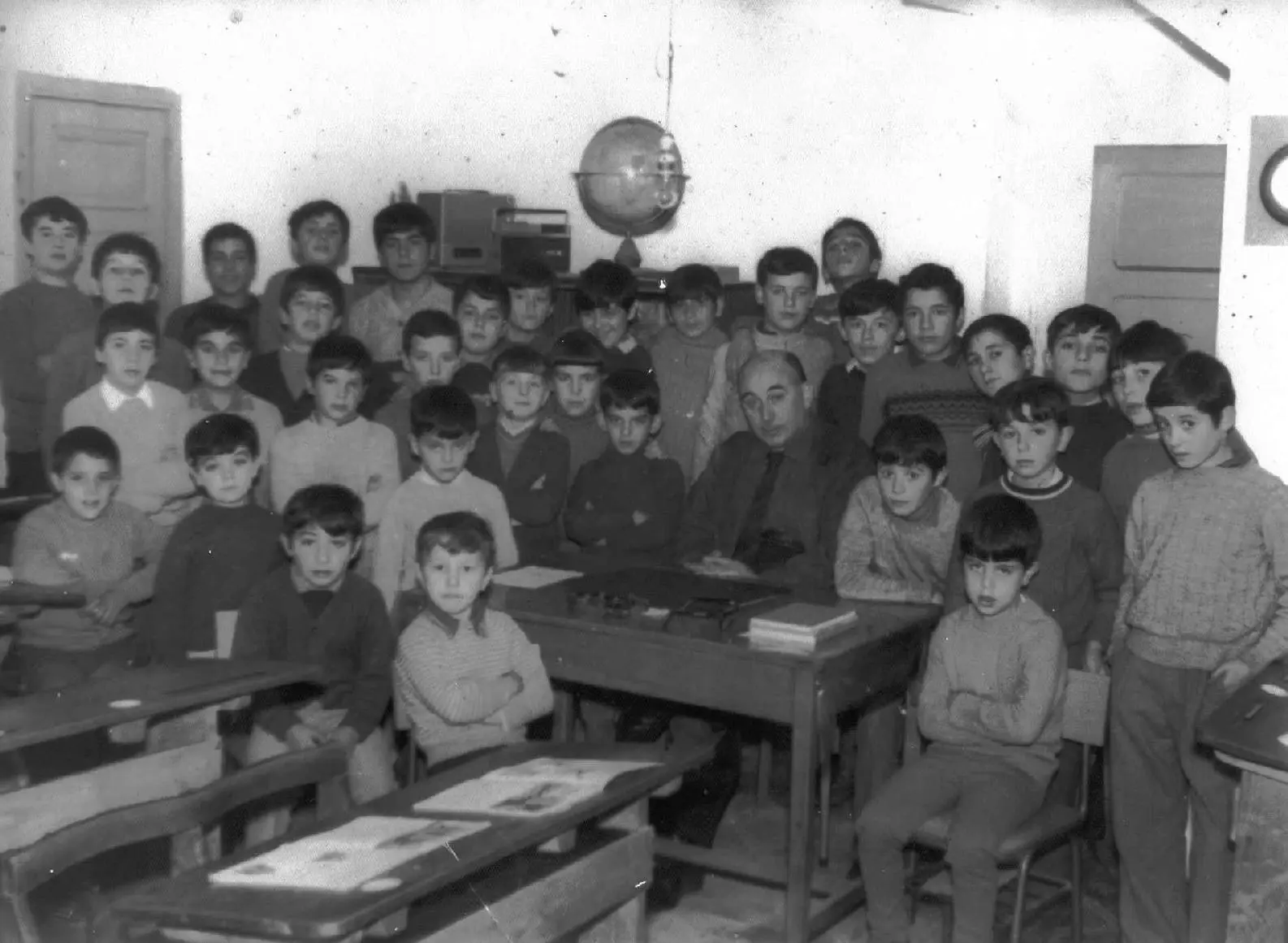

The teacher in Elviña was called Don Antonio. He adored that black boxer, Cassius Clay, later renamed Muhammad Ali to remove the inherited trace of slavery. We used to study a list of Visigothic kings, the great deeds of the conquistadors of America, but, in our school around the middle of the 1960s, the real king was Cassius Clay. All because of the teacher. To stand up or walk, he needed crutches. His legs were short and he rotated as he walked, leaving sudden, anatomical wakes in the air behind him. An illness from his childhood, they said. Apart from that, he was a well-built man with the neck of a bull. When he sat in his chair behind the desk, his smooth, prominent head that looked as if it had been varnished, his graphitic look, which was dark and shiny, turned him into a kind of hypnotic, feared idol. Even the globe, positioned on his desk or on top of the wardrobe that served as a library and archive, resembled a minor satellite orbiting that human star. When he moved, the motive power — his energetic head — kept the motionless part of his body on tenterhooks and seemed to carry the fate of the whole class. He had the added misfortune of living on an upper floor in a house near the school, which left him no choice but to climb and descend twenty steps every day. He did this on his own, leaning on his crutches. This was his battle. A struggle we pupils witnessed every morning, the way he came down, twisting and turning, confronting the malfunctions of his body on the lethal arena of the staircase.

Don Antonio was a rapid man, mentally agile, with a gaze that encompassed the invisible. From his panoptic perspective, he could see the classroom upside down and inside out. He couldn’t just read your thoughts. You could feel the trepanation, the way he extracted your thoughts and dissected them on the desk. Why didn’t he call out from the staircase? Why didn’t he let someone help him? He would glance over at us from the landing, while we watched him out of the corner of our eyes. The vision of his slow descent was the image of an epic, painful story, of wounded knowledge. The laborious passage became a kind of sinister rite. Nobody would have been surprised if a trapdoor had opened in the staircase one day and the teacher had disappeared.

Don Antonio’s school in Elviña

In class, he was efficient and hard. He could even be cruel when it came to corporal punishment, the way he moved his strong arm and the stick acquired an autonomous existence, detached from the brilliant brain. I can see him now, or at least I think so. The teacher’s perplexed gaze, the way he checks his own arm, having beaten a pupil. This used to happen a lot during catechism on a Saturday morning. Only the right answer would do. For some reason, he was always tense that day. We had to memorise everything, he never explained anything. He took the lesson, and there was no room for mistakes. Not even when it came to the episode with Balaam’s donkey. The stick and the ruler were work implements. They weren’t just taking up space. The first day of class, one boy would hand the teacher the instrument of punishment by order of his parents. Don Bartolo used it as much as Don Antonio. This wasn’t a topic that was ever discussed outside of class. Or in class, either. Don Antonio was competent. The one who taught best. Though he did have a problem with women. Not just with one or two. With the female race. With all of them, or so it seemed. The worst insult for a child was to be called a ‘little woman’. When he reached this limit, the tone of his voice would prick like a needle:

‘Little woman! You’re just like a little woman!’

Everything in him changed, speech and body, when a fight in the world heavyweight boxing championship was due to be broadcast. That day, he would transfer our class to the bar O da Castela, which had the only television in that part of Elviña. As far as I know, a unique, unprecedented move in Spain and perhaps in the world. He didn’t care what others might think. Cassius Clay versus Sonny Liston. The whole class in motion. And at the front, flying on Canadian crutches, a body making quick, abrupt strokes, in the direction of the ring, locked in combat with the world: the teacher.

15. You Will Never Be Abandoned

WE CHILDREN SLEPT on folding beds. This way, in the morning, when we got up, our bedroom could become the sitting room. From that window, you could see the city like a large, illuminated ship, the friendly light of the lighthouse, which proclaimed in Morse code, ‘You will never be abandoned!’ To the west, there were other, frightening glows that emanated from the furnaces and chimneys of the oil refinery in Bens. They looked like giant flamethrowers, an apocalyptic picture in the night, since that was where the sun set. On the other side of the house, where the front door was, there was only mountain. A mountain with a split personality. During the day, the unending forest, the so-called Priest’s Wood, was an undiscovered land for exploring, a place of adventures. At night, a hostile inferno, a place of loss, where the world’s bad temper muttered and groaned.

One night, my father threw María and me out of the house. We must have been about nine. We used to fight a lot back then, like cat and dog. He wasn’t in the habit of hitting. Nor was my mother. He would go to bed very early. For two reasons. Because at six he was already up, on his way to work. And because he didn’t want to pay the electricity company any more than he had to. He wasn’t a devotee of Our Lady of the Fist, but he was in permanent disagreement with the powers that ruled this world, be they the Vatican or Fuerzas Eléctricas del Noroeste. He had this intuition. Were we to follow his example, there would never be an energy crisis, nor would we suffer from climate change. He never gave way in his militancy against the electric empire. Even in his old age, when central heating was installed at home, he would silently go around turning off the radiators. When somebody complained about the temperature, he would keep quiet, like a member of the Secret Society of Disconnection. But back then we were reading like crazy and would await the arrival of the extinguisher of light with trepidation. He didn’t put on a show. This was a stealth operation. He can’t have enjoyed it, but the battle had to be won. We waited for a while. Until the sounds of sleep emerged from the master bedroom. Then we turned on the light. Like traitors.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Low Voices»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Low Voices» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Low Voices» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.