Manuel Rivas - The Low Voices

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Manuel Rivas - The Low Voices» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Harvill Secker, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Low Voices

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harvill Secker

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Low Voices: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Low Voices»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A brilliant coming-of-age novel from one of Spain’s greatest storytellers,

is a humorous and philosophical take on memory, belonging, and the nature of storytelling itself.

The Low Voices — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Low Voices», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I ran towards that place. I would have gone on Sundays if it had been open. I spent seven years at the co-ed institute: the six years of my baccalaureate and the one year of university orientation. It was on the side of the mountain, surrounded by meadows and fields, behind Oza Church. The first few years, it was little more than a shed with a flimsy roof and walls, always looking like a temporary shelter that fought bravely against the storms. What ever happened to Heraclitus, Parmenides, and the girl who bathed in the river?

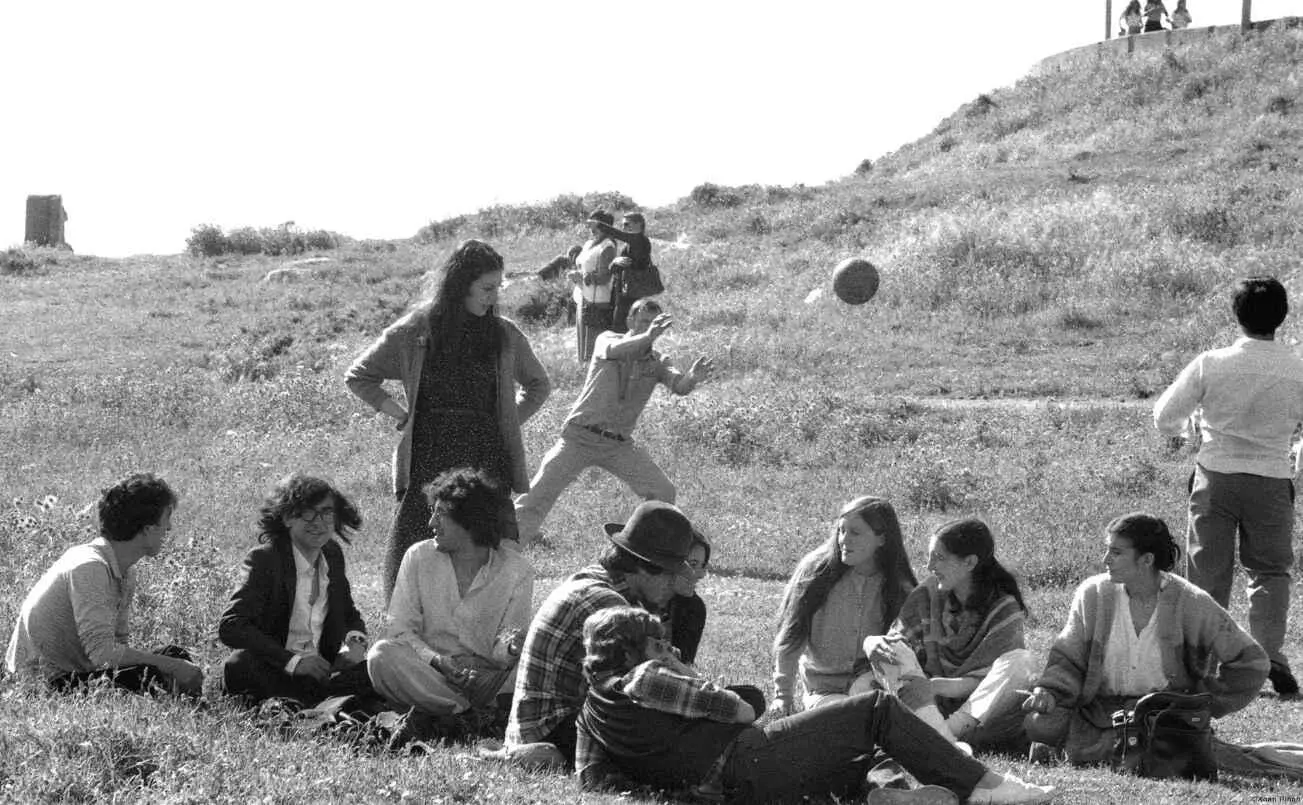

With María and others by the Tower of Hercules

For us, studying was a rash adventure. I mean for María and me. We were pushed by our primary school teachers, Don Antonio and Dona Fina. But this divided the family. It was uncommon back then for the children of a working-class family to continue their studies after school. My father wasn’t sure about this. And now I understand him. He saw me working on a building site and had already found a job for María as a sales assistant in a shoe shop. Not bad, right? She went to try it out for two weeks. One day, she came back from work and said, ‘I’m not going anymore. I want to be a student.’ María, when she was clear about something, wouldn’t budge. She had the soul of a suffragette. So students we were. She enrolled in A Milagrosa, a public institution that had links with the provincial orphanage. In the fourth year of her baccalaureate, María won a writing competition sponsored by a soft drinks manufacturer, in which all the teaching centres took part. First in A Coruña. Then in the whole of Spain. Her prize was a trip to Puerto Rico. The headline in the newspapers: ‘Bricklayer’s Daughter Wins National Writing Competition.’ That story by María, written when she was fourteen, was an unusual text imbued with beautiful harshness. The life of a tree, its felling, its journey to be cut into pieces in a sawmill. The kind of story that makes you ask, ‘How is this possible?’ A year after the award, María got rid of the presents she’d been given. Everything except for a few records of Puerto Rican music and a book of Tagore’s collected poems. She burned everything in the garden, under my mother’s silent gaze. My mother knew that freedom could hurt. A free woman was growing inside María, whose eyes were getting bigger and bigger, like bell jars. She didn’t stop crying the day of the coup in Chile, with the death of Salvador Allende. There were those who knew the reason, and others who asked, ‘But what’s wrong with the child?’ My mother kept quiet.

We had friends in common, who would pass each other on the way. Lots of them studied in Monelos. The place of studies coincided with the place of desire. The erotic place. The contrast between ‘place’ and ‘non-place’ is often a topic of discussion. There is ‘the other place’, where a second life is born. Something happened there. A psychogeographical concordance, a special set of teachers and a generation of stammering rebelliousness that wanted to say what one couldn’t say.

At the co-ed institute, we requested the hall for a free activity organised by pupils. The most daring group in the Monelos crew — Celsa, Xoana, Chuqui and Luciano — recited a poem by Bertolt Brecht that could well have been the slogan of those times: ‘How the Ship Oskawa Was Taken Apart by Her Crew’. We played records by Voces Ceibes. And interpreted The Peasant’s Catechism by Valentín Lamas Carvajal, that prodigy of insurgent humour written by a blind man at the end of the nineteenth century:

— Are you a peasant?

— Yes, for my sins.

The one asking the questions, the one playing the priest, was Pedro Morlán. And I was the peasant. Morlán made a very good confessor. Perhaps because of his presence — that of a tall, pale, thin, revolutionary young man. The ideal, the revolutionary dream, was in the air. There were some conservative teachers, but they were generally the most eccentric. Even the priests were Reds. First of all, Don Maurilio. And Rodríguez Pampín, who came later, timid in appearance, always deep in thought, the stony weight of the sky on his head. The complete opposite of Don Maurilio, who was a small, fibrous, electric kind of man. It seemed the whole of his body was at the service of his voice. For upholding masterly lessons or sermons with the salt of the earth. Through this priest, the son of peasant farmers in Castile, we learned about Hélder Câmara, the archbishop of Olinda and Recife who opened the way for liberation theology, about Ernesto Cardenal, and Camilo Torres, the Colombian guerrilla priest; we also learned the basic concepts of structuralism and psychoanalysis. The roots of a community were established. We saw through to the other side of scripture. Had Christ returned, he would have been crucified again on the spot. All you had to do was see the processions during Holy Week. But watching Don Maurilio demonstrate the existence of God by means of the atheist philosopher Althusser, who was very fashionable back then in intellectual circles, was no lesser spectacle. I say ‘watch’ because he used the blackboard a lot for his diagrams of Marxist structuralism, but always kept them within the limits of the blackboard. God appeared above the blackboard, on the throne of his superstructure. The most convincing argument that dispelled any doubts about faith was watching him play pelota. This stocky priest would roll up his sleeves and be transformed into pure, invincible infrastructure. With the co-ed institute surrounded by the jeeps of the Armed Police, the so-called ‘greys’, these priests had the courage to say a funeral mass for two shipyard workers shot dead at a demonstration in Ferrol on 10 March 1972. Pampín spoke Galician. And spoke inwardly. If Maurilio’s God was a historical optimist at the forefront of constructivism, for whom Bauhaus could be a continuation of Genesis, one imagined Pampín’s God as a vulnerable, existentialist being who was willing to shake hands with uneasy Nothingness, a creator more in need of protection than almighty. I went to the boarding house where he lived, a very modest room in Catro Camiños. He handed me a book and said, ‘Keep it hidden under your jersey and don’t take it out until you get home.’ It was Forever in Galicia by Alfonso Castelao, published in exile in America and known as the Galician Bible. A book that was used to being hidden and saying the things one couldn’t say. With humour and pain. Written by a man who was losing his sight. Aged, defeated, smothered by the advance of Nazism, suffering from survivor’s guilt, Castelao watches from his room, at dusk, how the windows of the buildings in Manhattan light up. He is exhausted. Alone. He writes, ‘I am the child of an unknown country.’ But something extraordinary happens. A groundswell. Chaplin’s walk. He goes to Harlem. It’s winter. He sketches a young black tramp. Possibly the best portrait of his life. ‘Listen,’ says my mother with the secular Bible in her hand, ‘what is Galicia’s Holy Trinity? The cow, the fish, the tree.’ Both priests, Maurilio and Pampín, were kind at a time that wasn’t. The Church wasn’t kind to them, felled as they were like trees.

Something else happened back then. Franco’s secret police, the Political — Social Brigade, paid a visit to the management of the co-ed institute. The acts of the ship Oskawa being taken apart by her crew on a Saturday came to an end, as did our experience of the freedom of the press on a cyclostyle. The management said it was for our own good. They were nice people. Teaching us a lesson. An intense, historical immersion. Now, it was fear’s turn. But we had already tasted freedom, the greatest sin in Spain. What one cannot say had infiltrated our molars. We had heard Michael Servetus on the lips of our teacher Caeiro: ‘ Libertatem meam mecum porto. ’ I carry my freedom with me. At the exit of the co-ed institute, there was always an ashen car containing men with an oblique glance. The Suburban Free Institute, the boys and girls, were under scrutiny.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Low Voices»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Low Voices» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Low Voices» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.