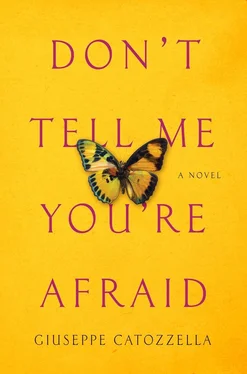

Though she did all she could to hide the fact, I knew that the Journey terrified her. How could it not? She was alone, she had no money, and she was prey to human traffickers called hawaian, beasts, who beat their victims like animals if they didn’t pay.

Sometimes she wrote that she was afraid, so afraid. Sometimes she couldn’t help telling me. And even though I was more afraid than she was, I would write: “Never say you’re afraid, abaayo, because if you do, the things you dream of won’t come true.”

It was what Aabe had taught me when I was little. You must never say you’re afraid, because if you do, fear — that vile, evil monster — will never go away.

“Never say you’re afraid, little Samia,” Aabe used to tell me, and I repeated the words now to Hodan. “Don’t say it.”

Because if you do, you won’t get to Europe.

But, as Allah willed, Hodan was among the lucky ones.

In early December of 2007, after traveling for only two months, she was able to board an old vessel that took her from the port of Tripoli to the coast of Malta.

She had arrived.

She had managed to defeat the monster.

She was in Europe.

THREE WEEKS AFTER HODAN’S ARRIVAL, when everything seemed sad and gloomy without her, I received the news that changed my life forever and that I’d been waiting for since the day I was born: I would compete in the Beijing Olympics the following year.

When Xassan called me into his office to tell me, I couldn’t believe my ears. As soon as he uttered the word “Olympics,” my mind went blank. He kept talking, but I couldn’t hear a word anymore.

“Samia, we think you can contribute a lot to our Olympic team and to our nation,” he began.

“Thank you, Xassan,” I replied.

“We value your efforts, your determination, and the will to win that you’ve been displaying.”

“Thank you again, Xassan.” It was the first time he’d summoned me to his office and said such things; I was trying to figure out where this was going.

“You won’t place very high, Samia… but we thought you should use it as a trial run for the next Olympic Games, the ones in London in 2012… to gain confidence…. So I’m asking if you feel up to going to China and running in those Olympics.”

At that point the world was suspended. All my thoughts converged on a single image, a snapshot of calm and serenity: a wicker chair, the slanting light of the sun filtering through a window, only partly illuminating the dusty, earthen floor, a room, Aabe and Hooyo’s, with me standing in front of Aabe promising him that, at seventeen, I would go to the Olympics.

And here came the tears. Two of them. The usual two.

Xassan thought they were tears of joy, and he made a joke that I only vaguely heard. But he was just half right. They came from deep inside, from my bitterness over the fact that Aabe was not there with me, that my sister wasn’t there to share my joy, and that my best friend had fled many years ago along with his entire family.

The Olympic Committee had chosen me and Abdi Said Ibrahim, a boy of eighteen who in recent months had become my new friend and training partner. At first this had aroused a poignant yearning for Alì, but I quickly tempered and dismissed it.

Abdi and I trained every day.

But with Al-Shabaab having become more and more powerful, things had worsened. Sometimes we couldn’t make it to the stadium because we were stopped by militants who insulted us or demanded money, accusing us of supporting Western countries. On those days we were forced to run on the street, amid smoking car tires and burning garbage in the squares, hoping not to come across other militiamen.

What’s more, even though I was an athlete on the Olympic team, I had to run covered. What I was doing, or in whose name, didn’t matter to anyone. I had to respect the laws of the Koran and cover my head, torso, and limbs.

One morning Abdi was stopped and two Hawiye militiamen stole his shoes. “You’ll run better that way,” they told him. “Nigger. This way you’ll run barefoot like a real African.”

We always tried to ignore it. We were determined to train with what we had: no coach, no personal trainer, no doctor, not even food. Not the type of nourishing food suitable for an athlete, with the right amounts of calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals. At times just the food required to live.

Hooyo earned less and less, almost nothing by now, and every so often we were forced to eat only angero, a kind of crepe, made on the burgico.

Bread and water.

There was one thing I did have, and it had become one of my most important possessions: the stopwatch. With it I measured my times. Whatever else might happen, I was obsessed with my times. They had to improve. If I didn’t see them improve from week to week, or if they worsened, I went into a deep funk that only Abdi could help me climb out of. In the end I started out again with even more energy.

We heard from Hodan frequently. She called us on Said’s cell phone, or we texted for hours on the Internet. She had settled in Malta and was engaged to Omar, a Somali boy whom she had met during the Journey. He had helped her a lot, and it was partly thanks to him that she had made it. She had told me about Omar right away; I’d realized that she had fallen in love the first time she spoke his name.

In April we received some wonderful news, which at first seemed impossible to accept but which later filled me with joy.

Our little Hodan — who was my older sister, true, but was still, along with me, the youngest in the family — was pregnant.

She told us one morning, right after she took the test and confirmed it. She was ecstatic. She and Omar had been living together for some time in Malta, in housing provided by the government and humanitarian organizations. They had decided to start a family and move up north, maybe to Sweden, maybe to Finland, where assistance for war refugees was even greater.

Each time we texted, Hodan said she felt that it would be a girl and that she would be like me, with fast legs. She told me that already, at twenty weeks, the baby was kicking like crazy.

That’s how I spent the four months before I was to leave for China: training, attending an occasional meeting at the Olympic Committee to learn how to improve Abdi’s and my times, and chatting happily with Hodan.

Hooyo, however, was increasingly concerned.

Aabe’s death and Hodan’s departure had made any separation, even if only temporary, unbearable to her. Whenever one of us brought up the subject of the Olympics, Hooyo’s eyes teared up. We told her she should be happy, that what was happening to me was very special, but by now she was able to see only the possible negative consequences of any event.

As might be expected, the news had spread quickly through the mutilated district of Bondere. The closer my departure came, the more people dropped by to see me and wish me well or bring me a small token of good luck. It happened almost every day before supper. These were all people with whom I’d grown up; they were my people, neighbors who had seen me born and develop into a young woman. People I loved and whose affection was for me a precious treasure.

“Have a safe trip, Samia, and bring honor to our country,” old Asiya said in a trembling voice; the elderly woman had held me in her arms the day I was born. I considered her a kind of grandmother, given that two of my natural grandparents had died and the other two lived far away, in Jazeera. “Take this,” she said as she handed me a cotton T-shirt. “I bought it at the market for your departure, to wish you good luck. I don’t know if you’ll want to wear it when you run….”

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)