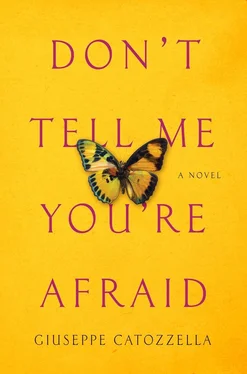

“We have to make a greater effort,” I insisted, pounding a fist on the mattress.

“No, our efforts will only lead to more violence. Don’t you see, Samia?”

No, not only didn’t I understand, but I didn’t believe it. “I have to stay here and continue running; this is my destiny. I have to win the Olympics, Hodan. I have to show the whole world that we can change. I have to keep the promise I made to Aabe…. This is what I must do.”

“You have a talent, Samia,” Hodan said quietly, putting a hand on my shoulder, “and it’s right that you continue to follow your path.” She dried her tears and blew her nose. She looked like Hooyo when she pretended she wasn’t moved. In that position, in that light, Hodan had our mother’s face. She had become a woman, and I hadn’t realized it. “What I dream of today, though, is to be free. Right now, unconditionally. I dream of having a family, as I could not do with Hussein. I dream that my children may grow up in peace. The war took away my husband, and I don’t even know for sure where he is.” She paused. “At this point I just need a new life, Samia.”

“I dream of being a free woman too, but I’m going to realize that dream here,” I said, shrugging her hand off my shoulder.

“Not me, Samia.” She was silent for perhaps a minute, but to me it seemed like a year or a millennium. “I’m leaving for Europe. Maybe I’ll get to England, like Mo Farah.” She tilted her chin up toward the photo, which still hung where I’d stuck it that long-ago night, next to the two medals from Hargeysa. “Or maybe Sweden or Finland.”

There was nothing more to say.

Hodan had made up her mind.

All I could do was use the time remaining before she left to resign myself to it, so I wouldn’t be unprepared and distraught when the time came and we had to separate.

I was beginning to think that the more I achieved in running, the more I lost in life.

AFTER THE RACE IN DJIBOUTI, the Olympic Committee gave me a pair of running shoes. The kind with cleats in the soles. But the thing that most changed my life was that I could go running at the stadium during the day, in sunlight.

Each moon that passed, however, was for me one less moon before Hodan’s departure. In the months that remained before our separation, I continued training as much as before, if not more. The tunnel I had entered with Aabe’s death had become even more endless. All I could do was lower my head and try to run my way out of it. I had just one goal: to keep from thinking and in that way qualify for the Beijing Olympics in 2008. As I had promised Aabe. I knew it all depended on me, on the times I’d be able to achieve on the track.

I dropped out of school because we couldn’t afford it anymore. The longer the war went on, the less money people had. The little money that Hooyo managed to bring home was needed for food.

Truthfully, I wasn’t too sorry, because that way I could run both in the morning and in the afternoon. By the time I got home in the evening, I was wiped out, but I didn’t care; I collapsed on the mattress before the others went to bed and woke up the next morning after a deep, restful sleep, full of energy.

I also tried, in my heart, to get used to the loss of Hodan’s singing, her caresses, the hand that squeezed mine before going to sleep. And she did the same.

For the second time we prepared to say good-bye. But this time we wouldn’t be seeing each other during the day at school.

We spent that period before the separation in a state of pathological attachment and, at the same time, of morbid rejection. If one of us came home and the other wasn’t there, we would search for hours and then, once found, not talk to each other. Or we fought as we had never done before, and when Hooyo or Said stepped in to have us make up, we’d burst into tears and hug each other tightly.

It was our tormented way of putting distance between us.

Two months later, in October 2007, Hodan left one night to set out on the Journey. She’d filled a small backpack with a few things; she had with her the shillings needed for the bus to Hargeysa, the requisite first stop for leaving the country, and not much more.

Without saying a word to anyone, she turned up that night ready to leave. She preferred to say good-bye without much fuss, especially for Hooyo’s sake. I wasn’t surprised; it was just like Hodan.

That way there was no time for lengthy good-byes and weeping. We held each other tight, and we all kissed her, Hooyo last of all. Before letting her go, Hooyo gave her a folded white handkerchief that held one of the small shells from the jar that Aabe had given her when they became engaged. Our portable sea, the one we would listen to when we were little. Hooyo tied the handkerchief to Hodan’s wrist.

Then Hodan was gone.

She left on foot, alone, to walk to the bus station.

Without even knowing what she would do once she got to Hargeysa. But that too was just like Hodan.

The Journey is something we’ve all had in our heads from the time we were born. Everyone has friends and relatives who did it, or who in turn know someone who did it. It’s like a mythological creature that can just as easily lead to salvation or death. No one knows how long it might take. If you’re lucky, two months. If you’re unlucky, as long as a year, or even two.

Ever since we were children, the Journey has been a favorite topic of conversation. Everyone has told stories about relatives who reached their destinations in Italy, Germany, Sweden or England. Scores of trailer trucks with men who perished, scorched by the sun, in the oven of the Sahara. Human traffickers and appalling Libyan prisons. Not to mention the numbers of travelers who die during the most difficult leg: crossing the Mediterranean from Libya to Italy. Some say tens of thousands, others say hundreds of thousands. We’ve been hearing these stories, these unsubstantiated numbers, since the time we were born. Because those who make it there always say the same thing when they call home: I can’t tell you what the Journey was like. It was horrific, that’s for sure, but words can’t describe it. That’s why it’s always shrouded in absolute mystery. A mystery that for some is necessary in order to reach safety.

Hodan, like all those who leave, knew only that she would get to northern Europe. That somehow she would cross those ten thousand kilometers. She would find a good man, she would get married again, have children and live a happy life. Every month she would send money home, a little for Mama and a little for me, to allow me to run, and she would wait until she was settled enough to be able to pay for the Journey for us too. That was what everyone did, and that much she knew, that much she had been told. Everything in between wasn’t worth thinking about.

And so, with a certain foolhardy unawareness, she left.

We, of course, were greatly concerned. We knew we could not expect any news, except occasionally, and this, rather than leaving us in the hands of blind hope, made us even more anxious.

Every so often, when she managed to find a phone somewhere, she would call us. Said had bought a cell phone, and we passed it around so Hodan could exchange a few words with each of us. At times, if there was an Internet connection available, like when she was in Sudan and then in Libya, we set a time an hour later when we would write to each other for hours. I went to Taageere’s, the only place close to home with a computer. We did this a few days in a row sometimes, when she was forced to stop someplace to wait until Said, Abdi, Shafici, or Hooyo managed to scrape together enough money to send her to pay the traffickers for another leg of the Journey. Hodan awaited the day when she would go and withdraw the money at the money-transfer booth the way one awaits death.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)