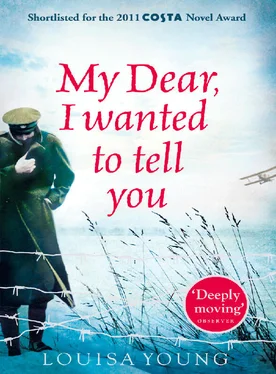

LOUISA YOUNG

My DearI Wanted to Tell You

Dedication

For Robert Lockhart

Contents

Title Page LOUISA YOUNG My DearI Wanted to Tell You

Dedication Dedication For Robert Lockhart

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Historical Note

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Louisa Young

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

France, 7 June 1917, 3.10 a.m.

It had been a warm night. Summery. Quiet, as such nights go.

The shattering roar of the explosions was so very sudden, cracking though the physicality of air and earth, that every battered skull, and every baffled brain within those skulls, was shaken by it, and every surviving thought was shaken out. It shuddered eardrums and set livers quivering; it ran under skin, set up counter-waves of blood in veins and arteries, pierced rocking into the tiny canals of the sponge of the bone marrow. It clenched hearts, broke teeth, and reverberated in synapses and the spaces between cells. The men became a part of the noise, drowned in it, dismembered by it, saturated. They were of it. It was of them.

They were all used to that.

In London, Nadine Waveney, startled from dull pre-dawn somnolence at the night desk, heard the distance-shrouded crumps and thought, for a stark, confused moment, Is it here? Zeppelins? She looked up, her face the same low pale colour as the flame of the oil lamp beside her.

Jean scampered in from next door. ‘Did you hear that?’ she hissed.

‘I did,’ said Nadine, eyes wide.

‘ France! ’ hissed Jean. ‘ A big ’un! ’ And she slid away from the doorway again.

Nadine thought, Sweet Jesus, let Riley not be in that.

In Kent, Julia Locke sat bolt upright in her bed before she was even half awake, saw the cupboard door hanging open and thought, foolishly: Oh . . . thunder . . . but she was sound asleep again when Rose, in her dressing-gown, looked in on her.

In the Channel, the waters wandered suddenly this way and that, in denial of the natural movements of tide and wind.

At Calais, a handful of late-carousing sailors paused and turned.

At Étaples, a sentry woke with a sharp nod that he felt certain would crack his head backwards off his neck. ‘Crikey,’ someone murmured, ‘hope that’s us, not them.’ Two ruins away, a sixteen-year-old whore paused and shrank, her heart battering and shaking. Her thirty-five-year-old punter fell away from her, unmanned as his blood hurtled elsewhere in his body.

Beyond Paris, a displaced peasant sleeping on a sack didn’t bother to wake. Sheep, less well-informed, panicked and ran to and fro. Their shepherds couldn’t be bothered to.

An upright piano stood in a field, gaping and rotting, where it had been since October 1914.

In the Reserve Line those who slept leapt awake; those who sat by dampened braziers jumped; those who leapt and jumped were pulled down by their comrades, with profanities and muffled cries of ‘Fuck sake, man.’ The Aussie sappers who had dug the tunnels under the German line, and laid the six hundred thousand pounds of mines, grinned and smoked. Ungentlemanly it might be, as warfare goes, but they had started that , with their filthy illegal gas – and, anyway, it’s effective. Which is all anyone cares about by now.

Up the line, the Allied men in their trenches reeled with the earth around them, and kept reeling until the earth around them let them stop. Above, a flock of starlings launched and circled, a counter-nebula of black on blue. Below, the fat rats scattered.

Across no man’s land, the soldiers flew up in the air, and fell, and the earth flew up in the air, and fell, and buried them whether they were dead or not.

And the German artillery responded, and it all doubled, redoubled, an exponential vastness, and in Berlin wives and girlfriends sat up at night desks and in beds.

Locke and Purefoy had been ready for it. That edge was on the night, the edge that leaked something coming . . . something else, beyond the ordinary filth. Everyone wore a dulled alertness, so when they started, though it was a shock, well, it was always a shock.

Locke was by the sack-flap entrance to the dugout, smoking, humming softly a song he was composing, about bats.

Purefoy was staring out through a periscope from the fire-step, thinking about Ainsworth, Couch, Ferdinand and Dowland, and Dowland’s brother, and Bloom, Atkins, Burdock, Taylor, Wester . . . and the rest. He was reciting their names, all the names he could remember, and their qualities, and trying to remember their faces, and their voices, their Christian names, and their little ways, and how they had died, and when, and where.

As the string of mines went monumentally up across the way, little landslides of earth trickled down from the ratty timber-and-sandbag ceiling on to their tea-chest desk. Locke grabbed his head, elbows round his ears. He barked, loudly, wordlessly – then flung his arms out, and strode into the body of the trench. Purefoy was already moving along the line, joking, clapping the men on their shoulders.

In the answering barrage of shells, one took the edge off the parados twenty feet along. Purefoy and Locke and their companions flung themselves down in the homely mud of their trench, that six-feet-deep poisoned haven with which they were so familiar and, crouched under the parapet, shared the peculiar safety of knowing that the worst was already happening.

Chapter One

London, towards Christmas, 1907

On a beautiful day of perfect white snow, cut-blue sky and hysterical childhood excitement, Nadine Waveney’s cousin Noel threw a snowball in Kensington Gardens. It hit a smaller boy they didn’t know, smack on the side of the face, causing him to gasp and shout and lose his footing, and knocking him on to the uncertain icy surface of the Round Pond. Still shouting, the boy, whose name was Riley Purefoy, crashed through the filmy frozen layers – and shot out again, gasping, shaking slush and icy water off himself until his hair stood on end, and laughing uproariously. Noel, who was bigger, stared at him, unsure. Nadine, standing back, smiled. She liked that the smaller boy was laughing. She’d seen him before in the park. He was always scrambling about, climbing things, collecting things. Once they’d come face to face halfway up a conker tree, deep in the green leaves. He’d had a pigeon feather in his hair, like an Indian warrior. He’d laughed then as well.

Jacqueline Waveney, well dressed, high-cheekboned, self-consciously verging on Bohemian, insisted on bringing Riley home to warm and dry him. They lived close: just across the Bayswater Road from the park gate. ‘Everyone comes here when they fall in,’ she told him, as they scurried along the path to the gate. ‘Or if they get rained on. We’re the first stop for people in trouble in the park.’ Her smile was warm and her accent strange – French, though Riley didn’t know that then.

The house was huge to him, though quite small to them. He was taken through a hall to the drawing room: ‘droing room’, Jacqueline said. Riley looked at the tall ceiling, the creamy panelling, the velvet sofas, the warm fire, the glossy peacock-green tiling around it. Inside, Mrs Waveney had him wrapped in a towel, and his clothing taken away to be hung on the boiler. He was given hot chocolate to drink, and some dry clothes to wear, too big for him. The people stood around him, noticing, but not seeming to mind, that he was really quite a common little boy.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)