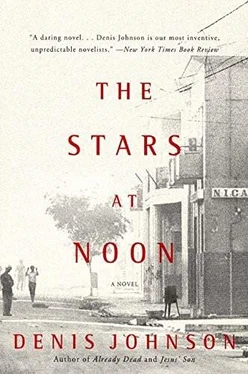

Denis Johnson - The Stars at Noon

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Denis Johnson - The Stars at Noon» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2007, Издательство: Harper Perennial, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Stars at Noon

- Автор:

- Издательство:Harper Perennial

- Жанр:

- Год:2007

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Stars at Noon: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Stars at Noon»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

is a story of passion, fear, and betrayal told in the voice of an American woman whose mission in Central America is as shadowy as her surroundings. Is she a reporter for an American magazine as she sometimes claims, or a contact person for Eyes of Peace? And who is the rough English businessman with whom she becomes involved? As the two foreigners become entangled in increasingly sinister plots, Denis Johnson masterfully dramatizes a powerful vision of spiritual bereavement and corruption.

The Stars at Noon — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Stars at Noon», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Okay then, let’s take the back door. It’s nailed, we’ll have to pry it.”

“He’ll hear us. He’s listening.”

“I’m taking the back door. I’m leaving.”

“Well and good, then.” He stood quite still.

Instead I hit my purse for the rum. “I don’t see why I should have to leave,” I said. “Nobody’s after me.”

“I’ll have some of that,” he said about my rum.

In a few seconds, I sat on the bed. “What did you do?”

He sat down beside me. “I told you. Didn’t I? I can’t remember what I've told to whom, by this time.”

Among the two dozen noises coming in through the window, there were twenty I couldn’t identify. That's where that raw feeling comes from when you’re run up on a foreign shore — nothing’s identified. You just can’t take enough for granted. “You work for Watts Oil, you said. That doesn’t make you a spy.”

“I’ve given away the company’s secrets.”

“Right, you said that, but — doesn’t your company sell gasoline? What’s all the fury about?”

“We take petroleum out of the earth to keep everybody alive, for Christ’s sake — it’s the biggest game going.”

“But I mean anyway. How big a secret can your secrets be?”

“Well,” he said, “listen, the location of these things, deposits and so forth, I’m surprised at you, where do you spend your time that you don’t know governments take a deep intertest?”

I was seeing it now. “You told Nicaragua something,”

“I jolly damn well did, about the location of an oil deposit. A possible location.”

“Possible? You mean maybe it isn’t even there?”

“Testing’s begun. That’s the full extent of it. There may be a batch under Lake Nicaragua, and if it’s there, it spills over into Costa Rica. Costa Rica already knew of it. Nicaragua had a right to the information, it seemed to me.”

“So you blew it around, what a fool. And now this Costa Rican is after us.”

“He’s not after us. He has us.”

An idea suggested itself: “I think we should kill him.”

“Do you.”

“Then we’d have his jeep.”

“And his wallet and his trousers. And his body.”

“We could put the body in the trunk.”

“I don’t believe that thing has a trunk.”

“Are we speaking seriously about this?”

“Of course not,” he said, “for goodness’ sake. Do you know, I was warned about you. People said, Nicaragua, my God, there’s a guerrilla war on, the place is full of killers. Only they meant foreign killers.”

“Down here, we’re the foreigners. We’re the ones without any documents on file, no fingerprints, no relatives.”

“I hadn’t thought of it that way.”

“We’re alone, we can’t be touched,” I insisted, “we’re dangerous.”

“I’m not dangerous,” he said. “I would never kill anyone.”

“But you’d screw yourself all up. You’d get yourself in a corner way far away from home, wouldn’t you? Spreading it around about oil wells.”

“I had a notion everybody should start even.”

“Start even, oh,” I said, “now there’s a notion that doesn’t apply here at all.”

Now he was crying about what he’d done to himself. “I told them,” he said, “and they told Costa Rica that I’d fucking told them, you see.”

He was waking up to it slowly. Gradually and enormously the dawn of all he’d done to himself . .

“I could say anything right now,” I told him, “and it wouldn’t matter.”

“Then help me. .”

I’d done only one thing to help him — I’d tried to call him on the phone and warn him — but that one good deed had set me over the brink, and I felt myself slipping down with him . . In order to stop helping him, I had to help him a little longer. .

“They’re sort of after me, too,” I admitted, “at least to the point where I don’t want to talk to them, or him. Or anyone.”

He didn’t answer.

“We’re a hell of a pair. You know what, I spend almost every day doing nothing. Do you realize that? Once every two weeks I get slightly off the wall. Why did you have to coincide?”

He took out his wallet and started looking at all the things in it, the business cards and identification cards and so on, weeping.

There was no consoling him. “I suppose you love your family and all that,” I said anyway.

“Yes, yes, I do. I do love my family.”

He cried without shame, like a girl. .

What a fate!

Every time I turn around, they’re jamming something under somebody’s fingernails, and I’m supposed to watch.

~ ~ ~

I HAD to observe him. In fact they were upping my voltage, weren’t the little demons, doing away with whatever was formerly unimaginable, putting before me for observation the most horribly tormented soul of all, the humanitarian among the damned — dressing him in a blue suit, grooming him presentably, handing him an appointment book. . Believe me, looks deceive: among these souls he would have liked to help, with their diesel-blackened nostrils, their gnarled, arthritic hands and shrivelled guts, their faces rubbed away against the wheel of need, among these he was most definitely the pick hit, the big contender, the one to watch. .

Next morning I got the Señora to unlock the phone for me. This equipment wasn’t there for customer use, but the Señora never minded. She liked me — always looked away from me, smiling in a tight-lipped way. The General of Maids seemed fond of me, too. They didn’t know who I was but they knew I wasn’t holding any terribly high cards.

I needed to check on the Englishman’s luggage. Also I had to find us another place to stay — where I was living now just wouldn’t do anymore, decorated as its entrance was by the off-course policeman from Costa Rica. He seemed to feel at home here. At dawn he’d been stomping around out in the lobby, invoking childhood terrors. He answered to no one and nobody questioned him.

Even now this OIJ person watched me through the window, at the same time eating his breakfast of freshly sliced mango out of a little plastic bag. He sat on the fender of his jeep, eating with his fingers, leaning forward with his feet wide apart in order not to dribble on his shoes.

First I dialled the Inter-Continental, because it was just such a pleasure dialling the Inter-Continental: somebody always answered right away. But nobody of real authority ever wanted to get on and converse. The desk clerk transmitted dreams and legends as to when the manager might appear. . Obviously I’d have to go over and find this manager myself.

The line started crackling in a jazzy fashion. Just before the telephone died, I got through to another motel and found us new accommodations.

Back in my room —my room — the Englishman was just in the process of smelling his shirt before putting it on for the third immolating tropical day. .

I told him I was off to the Inter-Continental and served him a number of counterfeit assurances as to his luggage.

“Please, by all means, find me a pair of undershorts that aren’t completely soggy,” he begged.

The Costa Rican outside didn’t budge or blink when I left, he just sat on his fender with his sunglasses parked on his scalp — a greasy habit that — committed, I supposed, to following the Britisher only.

I smiled at him, but I was faking it, I felt much more like crying . . If only a self-admitted Costa Rican cop in Nicaragua had made any sense at all, I wouldn’t have feared him quite so hysterically.

But while I looked for a cab, oh! the revitalizing surges of my economic status. . These gypped Coca-Cola addicts heaving around the streets with their empty bellies couldn’t help looking at me with a certain supernatural awe — financially, I was spectacular, miraculous; the minute I hit the pavement, the day’s rivulet of cordobas started flowing from my hands. . “Mother,” the cabdrivers shouted, “soothe my coffers.” Mother, the mutilated posters cried, where they speak your name it says Money . . I intended to ditch my British friend today. But I wanted to stay with him, too, I liked being naked with him, the way he smelled made me feel both hungry and sorry, I liked knowing we were in for it, that we didn’t have far to go. . “Mother-I-am-penniless-it-hurts — intercede-for-me-in-your-mercy,” the boys out front of the Inter-Continental pleaded. “Mother, let me go through your pockets,” wept the desk clerk. What a morning! . . If I’d been the fattest woman on earth, or blasting away with a bazooka, they couldn’t have treated me with more respect. . All but the doorman, who must have known me from the night shift, and failed pointedly to operate his equipment. Now it turned out that the fugitive manager had left a suitcase belonging to the Englishman, also a piece of his hand-luggage, in the hotel’s travel office, right next to the desk of a lady who spoke English and didn’t care whom I claimed to represent, if I wanted these bags I could take them. “Get a real job, you sorry fuck,” I told the doorman by way of a tip, and dragged this stuff out front myself, and was carried off in my taxi with a trunk full of I didn't know what.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Stars at Noon»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Stars at Noon» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Stars at Noon» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.