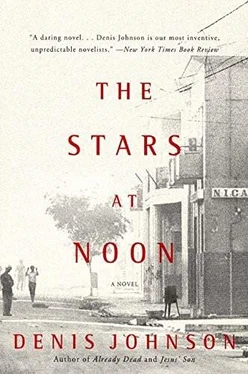

Denis Johnson

The Stars at Noon

. . what we are looking for

In each other

Is each other,

The stars at noon,

While the light worships its blind god.

W. S. MERWIN

THE AIR was getting thick — if you like calling a garotte of diesel and greasy dirt “air”—and so before the burning rain began I stepped into the McDonald’s. But right away I caught sight of the grotesque troublemaker, the pitiful little fat person whose name was forever escaping me, Sub-tenente Whoever from Interpren, getting out of his black Czechoslovakian Skoda and standing there on the dark street with my fate in his hands . . If I didn’t go to bed with him again soon, he was going to lift my card.

I hoped it wasn’t me he was waving at, but I was the only customer in the place. I’ve always been the only patron in the McDonald’s here in this hated city, because with the meat shortage you wouldn't ever know absolutely, would you, what sort of a thing they were handing you in the guise of beef. But I don’t care, actually, what I eat. I just want to lean on that characteristic McDonald’s counter while they fail to take my order and read the eleven certifying documents on the wall above the broken ice-cream box, nine of them with the double-arch McDonald’s symbol and the two most recent stamped with the encircled triangle and offering the pointless endorsement of the Junta Local de Asistancia Social de Nicaragua. . It’s the only Communist-run McDonald’s ever. It's the only McDonald's where you have to give back your plastic cup so it can be washed out and used again, the only McDonald’s staffed by people wearing military fatigues and carrying submachine guns.

I let go of my supper plans and headed for the ladies' room in the hallway leading to the kitchen.

The two soldiers leaning against the drinking fountain looked between me and the approaching Sub-tenente with slow eyes that said they understood what was happening and were completely bored by it.

I thought I’d wait him out in the ladies' room, doing nothing, only sweating — needless to say, I wouldn’t go so far in such an environment as actually to raise my skirts and pee; and the walls were too damp to hold graffiti. . I was sure the Sub-tenente hadn’t got a good enough look to say it was me—

He came around anyway and stood outside the door and coughed.

“Señorita.”

I turned on the faucet, but it didn’t work.

“Señorita,” Sub-tenente Whoever said.

I tried the toilet, which flushed but didn’t refill. . Just the same, the sight of a more or less genuine commode, with a handle and a cover-and-seat, functioning or not. . Nothing fancy, but a lot of the lavatories down here don’t have toilets, that is, the room itself is designed to be one monstrous toilet, with water running down the walls and gradually, over the course of days, influencing substances toward tiny plugged-up drains in the corners.

The Sub-tenente knocked on my door now. This seemed, all by itself, a slimy presumption. He cleared his throat. . Costa Rica was just across the border. But they would never let me out of this country.

“Señorita,’’ he said through the door, “may you tell to me if you are intending to remain very long?”

I looked for toilet paper, but there wasn't any toilet paper and there never would be toilet paper — south of here they were having a party with streamers of the stuff, miles and miles of toilet paper, but here in the hyper-new, all-leftist future coming at us at the rate of rock-n-roll there was just a lot of nothing, no more wiping your bum, no more Coca-Cola, no beans or rice: except for me they got no more shiny pants, no more spiked heels. No unslakeable thirst! No kissing while dancing! No whores! No meat! No milk! South of here was Paradise, average daily temperature 71 °Fahrenheit, the light sad and harmless, virgins eating ice-cream cones walking up and down—

“Señorita, if possible I will wait for you . .”

Still I thought I could hold out a few seconds longer, hugging the wall — drugged, like a little kid, by the taste of my own tears on my lips . .

“Señorita. Señorita. Señorita,” said the Sub-tenente.

He said something to the soldiers outside and everybody laughed.

“Si. Si. Si,” I said. I opened the door. “Sub-tenente Verga!”—which wasn’t his name, but “verga” means prick —“It’s so good to see you again!”

I DIDN’T think this would take long. . And it didn’t. .

We were doing it on the couch tonight: it was either that or the rug. . His clothes, civilian clothes, lay in a heap beside mine — I’d never seen Sub-tenente Whoever in uniform. He was a spy, or something like that. I believe anybody who thought about it would have said he affected the goat-like Lenin look, but in truth his features were unshaped, they seemed to be materializing out of a bright fog, nothing more than a shining blank with shadows floating on it. . Even as he coasted back and forth above me with the lamp behind him, the oval of his face gave out a mysterious light, like the exit from a tunnel. . “Are you looking at me,” I asked him softly, but he was sighing and hiccuping too loudly to hear. I hoped he wouldn’t go on long enough to make me sore. I started to worry that maybe I was too thin for him, it’s a fact that I’m always either too fat or too skinny, I can’t seem to locate the mid-point. Not that the pleasure and comfort of an incompetent small-time official in a floundering greasy banana regime surmounts my every concern, but all men tend to grow innocent, wouldn't you agree, at the breast. . You can’t help feeling a little something, if only a small sharp pity, as if you’d just stepped on a baby bird. The bird was going to die anyway, you only shortened its brainless misery . . “Are you coming? Are you coming?” I was speaking English. He probably didn’t know what I was talking about. .

Through it all I wept and sniffled, I did it all the time, it was becoming a kind of trademark.

The Sub-tenente spoke softly, he stroked me, he was thankful, what a laugh, if only they knew how obvious they all are!

And here we languished perspiring in his bureaucratic tristoire with its slatted shutters, and also, even, a rug. . Cozy. . But in this climate generally you didn’t want cozy. Anything but.

“Do you have any talcum powder?” I asked him.

Already he was engaging the routine — acting like he’d skipped some critical errand and couldn’t remember what. “Qué?” Getting on his shirt like he was late for an appointment, and so on.

“Polvos de talco, baby?”

“Oh. Si. Si,” and he started toward the bathroom, changed his mind. “No. No.” He spoke in Spanish now: "Listen to me. I want to tell you something.”

“Yes—”

“The moment has come when I must take your press card and your letter of authority.”

“What are you saying?”

“You are not a journalist.”

“But I am. Yes.”

“No.” He held my purse in one hand and searched through it with the other.

“Yes.” I snatched the purse from him and he shuffled quickly through some papers his hand had come away clutching. He picked out the letter he’d written authorizing me to visit various locations in the capacity of a journalist.

I was naked, but I suppose that was my armor. He tossed my other papers on the bed and held out his hand, but didn't come at me.

“And your press card. It’s necessary for me to ask for your press card also. Also.”

“I don’t have it.”

“Yes. You have it.”

“It’s in my room at the motel.”

Читать дальше