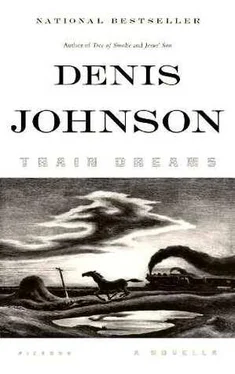

Denis Johnson

Train Dreams

In the summer of 1917 Robert Grainier took part in an attempt on the life of a Chinese laborer caught, or anyway accused of, stealing from the company stores of the Spokane International Railway in the Idaho Panhandle.

Three of the railroad gang put the thief under restraint and dragged him up the long bank toward the bridge under construction fifty feet above the Moyea River. A rapid singsong streamed from the Chinaman voluminously. He shipped and twisted like a weasel in a sack, lashing backward with his one free fist at the man lugging him by the neck. As this group passed him, Grainier, seeing them in some distress, lent assistance and found himself holding one of the culprit’s bare feet. The man facing him, Mr. Sears, of Spokane International’s management, held the prisoner almost uselessly by the armpit and was the only one of them, besides the incomprehensible Chinaman, to talk during the hardest part of their labors: “Boys, I’m damned if we ever see the top of this heap!” Then we’re hauling him all the way? was the question Grainier wished to ask, but he thought it better to save his breath for the struggle. Sears laughed once, his face pale with fatigue and horror. They all went down in the dust and got righted, went down again, the Chinaman speaking in tongues and terrifying the four of them to the point that whatever they may have had in mind at the outset, he was a deader now. Nothing would do but to toss him off the trestle.

They came abreast of the others, a gang of a dozen men pausing in the sun to lean on their tools and wipe at sweat and watch this thing. Grainier held on convulsively to the Chinaman’s horny foot, wondering at himself, and the man with the other foot let loose and sat down gasping in the dirt and got himself kicked in the eye before Grainier took charge of the free-flailing limb. “It was just for fun. For fun,” the man sitting in the dirt said, and to his confederate there he said, “Come on, Jel Toomis, let’s give it up.” “I can’t let loose,” this Mr. Toomis said, “I’m the one’s got him by the neck!” and laughed with a gust of confusion passing across his features. “Well, I’ve got him!” Grainier said, catching both the little demon’s feet tighter in his embrace. “I’ve got the bastard, and I’m your man!”

The party of executioners got to the midst of the last completed span, sixty feet above the rapids, and made every effort to toss the Chinaman over. But he bested them by clinging to their arms and legs, weeping his gibberish, until suddenly he let go and grabbed the beam beneath him with one hand. He kicked free of his captors easily, as they were trying to shed themselves of him anyway, and went over the side, dangling over the gorge and making hand-over-hand out over the river on the skeleton form of the next span. Mr. Toomis’s companion rushed over now, balancing on a beam, kicking at the fellow’s fingers. The Chinaman dropped from beam to beam like a circus artist downward along the crosshatch structure. A couple of the work gang cheered his escape, while others, though not quite certain why he was being chased, shouted that the villain ought to be stopped. Mr. Sears removed from the holster on his belt a large old four-shot black-powder revolver and took his four, to no effect. By then the Chinaman had vanished.

Hiking to his home after this incident, Grainier detoured two miles to the store at the railroad village of Meadow Creek to get a bottle of Hood’s Sarsaparilla for his wife, Gladys, and their infant daughter, Kate. It was hot going up the hill through the woods toward the cabin, and before getting the last mile he stopped and bathed in the river, the Moyea, at a deep place upstream from the village.

It was Saturday night, and in preparation for the evening a number of the railroad gang from Meadow Creek were gathered at the hole, bathing with their clothes on and sitting themselves out on the rocks to dry before the last of the daylight left the canyon. The men left their shoes and boots aside and waded in slowly up to their shoulders, whooping and splashing. Many of the men already sipped whiskey from flasks as they sat shivering after their ablutions. Here and there an arm and hand clutching a shabby hat jutted from the surface while somebody got his head wet. Grainier recognized nobody and stayed off by himself and kept a close eye on his boots and his bottle of sarsaparilla.

Walking home in the falling dark, Grainier almost met the Chinaman everywhere. Chinaman in the road. Chinaman in the woods. Chinaman walking softly, dangling his hands on arms like ropes. Chinaman dancing up out of the creek like a spider.

He gave the Hood’s to Gladys. She sat up in bed by the stove, nursing the baby at her breast, down with a case of the salt rheum. She could easily have braved it and done her washing and cut up potatoes and trout for supper, but it was their custom to let her lie up with a bottle or two of the sweet-tasting Hood’s tonic when her head ached and her nose stopped, and get a holiday from such chores. Grainier’s baby daughter, too, looked rheumy. Her eyes were a bit crusted and the discharge bubbled pendulously at her nostrils while she suckled and snorted at her mother’s breast. Kate was four months old, still entirely bald. She did not seem to recognize him. Her little illness wouldn’t hurt her as long as she didn’t develop a cough out of it.

Now Grainier stood by the table in the single-room cabin and worried. The Chinaman, he was sure, had cursed them powerfully while they dragged him along, and any bad thing might come of it. Though astonished now at the frenzy of the afternoon, baffled by the violence, at how it had carried him away like a seed in a wind, young Grainier still wished they’d gone ahead and killed that Chinaman before he’d cursed them.

He sat on the edge of the bed.

“Thank you, Bob,” his wife said.

“Do you like your sarsaparilla?”

“I do. Yes, Bob.”

“Do you suppose little Kate can taste it out your teat?”

“Of course she can.”

Many nights they heard the northbound Spokane International train as it passed through Meadow Creek, two miles down the valley. Tonight the distant whistle woke him, and he found himself alone in the straw bed.

Gladys was up with Kate, sitting on the bench by the stove, scraping cold boiled oats off the sides of the pot and letting the baby suckle this porridge from the end of her finger.

“How much does she know, do you suppose, Gladys? As much as a dog-pup, do you suppose?”

“A dog-pup can live by its own after the bitch weans it away,” Gladys said.

He waited for her to explain what this meant. She often thought ahead of him.

“A man-child couldn’t do that way,” she said, “just go off and live after it was weaned. A dog knows more than a babe until the babe knows its words. But not just a few words. A dog raised around the house knows some words, too — as many as a baby.”

“How many words, Gladys?”

“You know,” she said, “the words for its tricks and the things you tell it to do.”

“Just say some of the words, Glad.” It was dark and he wanted to keep hearing her voice.

“Well, fetch, and come, and sit, and lay, and roll over. Whatever it knows to do, it knows the words.”

In the dark he felt his daughter’s eyes turned on him like a cornered brute’s. It was only his thoughts tricking him, but it poured something cold down his spine. He shuddered and pulled the quilt up to his neck.

All of his life Robert Grainier was able to recall this very moment on this very night.

Forty-one days later, Grainier stood among the railroad gang and watched while the first locomotive crossed the 112-foot interval of air over the 60-foot-deep gorge, traveling on the bridge they’d made. Mr. Sears stood next to the machine, a single engine, and raised his four-shooter to signal the commencement. At the sound of the gun the engineer tripped the brake and hopped out of the contraption, and the men shouted it on as it trudged very slowly over the tracks and across the Moyea to the other side, where a second man waited to jump aboard and halt it before it ran out of track. The men cheered and whooped. Grainier felt sad. He couldn’t think why. He cheered and hollered too. The structure would be called Eleven-Mile Cutoff Bridge because it eliminated a long curve around the gorge and through an adjacent pass and saved the Spokane International’s having to look after that eleven-mile stretch of rails and ties.

Читать дальше