He wonders if Misty is having sex with Cody or Black Dog. Possibly, seeing as she appears to be under the influence of drugs, and anything can happen under those conditions. His heart begins to race. For that matter, seeing as drugs are in the picture, why not with both men at the same time?

Parsifal can feel his face turn hot.

He walks back down the hill. He has to find that cup.

Parsifal supposes that trudging through the woods, hour after hour without any signs of hope, might be discouraging to many people, but for him, alone again in the woods, it seems almost as if his scars, from the fire and other things, have disappeared, except, of course, for the mark left by lightning.

His ankle feels a little better.

With Cody and Black Dog?

When Parsifal thinks about blindness, he thinks about all the ways that people can lose sight: some at birth, some later, slowly or all at once. Others lose it, then get it back again, then lose it forever. And just as the way in which blindness arrives must inevitably alter its effect, surely the varieties of not-seeing must differ as well. Some see black, others purple, red, explosions of color, and possibly even experience moments when the curtain between the eyes and the world is parted for an instant, then comes crashing shut again. Or things may dissolve over weeks or years, like a dark lozenge left in a glass of water, until over time the actual lozenge is invisible, a part of the now-dark water. Or the field of vision may become covered with spots, like splotches on a shower door, until it’s impossible to see if there’s anyone else there in the bathroom along with you. Or that same field, once large, may start to shrink, like the closing credits of a cartoon, a circle growing smaller until nothing’s left but a dot, then black.

So Parsifal had been walking and thinking this and that, when suddenly he came upon a sight that stopped him cold: a rectangular hole in the ground, about three feet wide and six feet long. It looked to be about two feet deep and was not the result of any falling object. Or that’s the way it is now , he thought, with increasing excitement. Twenty or so years ago the hole would have been deeper, empty of debris, the sides steeper, and the bottom filled with the sort of deadly pointed stakes that he himself had pounded in as a child, the sharp ends pointing upward.

Twenty or so years ago it would have been a perfect trap for catching a deer that, walking down its usual trail, would not have noticed that a pit had been dug there overnight and covered with branches and leaves so it looked the same, except for the pile of dirt to one side, as the rest of the forest floor. Then the deer, as frequently happened, would stumble in and be unable to get out. The following morning, or next day, or the day after that, Parsifal would find the unfortunate animal, usually still alive, impaled on the pointed stakes he had set in the ground and in terrible agony, and he would dispatch it with a rock. After it had finally ceased to move, Parsifal would lower a ladder made of sticks to climb down and lift it out. Then he would drag its body back to Pearl, who would skin and cook it for their dinner. She said that living in the forest had made Parsifal strong for his age.

His infinite wisdom.

It was not just the odd deer he caught, either, because, skilled in woodcraft as Parsifal was, he frequently helped his mother by making snares for small animals (rabbits, possums, and squirrels) and deadfalls for medium-sized ones (raccoons and badgers and the occasional fox). But now, finding what may well have been a pit that Parsifal himself had dug twenty years ago meant two important things: First, that he was in the right forest. Second, the location of his old house must be nearby, because even as strong as he had been in those days, he still tried to dig his pits so his victims would be within easy dragging distance of home.

Parsifal had to be sure, however. Carefully, he lowered himself down the sides of the pit to the bottom, where, much as he expected, he sank another few feet into the collection of leaves and branches that had collected there over the past two decades. Were there pointed stakes? He had avoided them by staying close to the walls, but now he reached toward the center and fished around beneath a pile of debris. Yes. His fingers closed carefully around what seemed to be a pointed stake, and he carefully tugged it out of the ground. The point had been dulled by time, and the bottom had almost completely rotted away, but there it was. He was the person who had dug that pit, and sharpened the stakes, and lined the bottom. This pit was his.

When Parsifal climbed back out, he was exhausted. He spread his sleeping bag out there and then, alongside the pit, built a small fire, and, still clutching that rotting, formerly so-pointed stick, fell straight asleep.

That night Parsifal dreamed he bit into a fortune cookie that was full of blood.

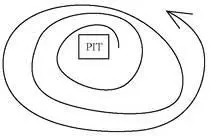

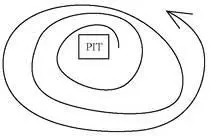

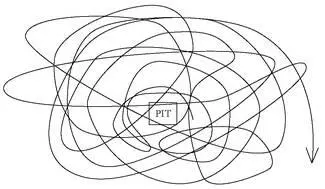

Encouraged by the discovery of the pit, Parsifal woke, put out his fire, ate another energy bar — a fig and peanut variety — and began his search anew, springing up hills and bounding down them again, rapidly intending to conform to the following plan:

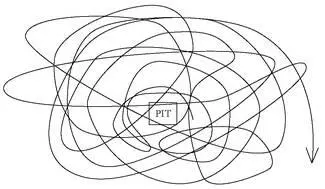

The forest raced by in a whirl of brown and green, tree trunks and leaves, bushes and grassy patches, and little creeks filled with rocks, and crawfish and tadpoles and newts. He didn’t know what Misty had put in those energy bars, but they packed a wallop, and it wasn’t until a couple of hours had passed that he realized that not only did he have no idea where he was, he couldn’t even tell if he had already searched the section he was presently occupying. Whatever that was.

He scanned the ground, hoping to find another pit, but found none, not even the hole he had slept alongside.

At lunchtime, even though he wasn’t particularly hungry, Parsifal made a small fire in a clearing and brewed a cup of tea in order to get his bearings. It is just for this reason — and also because it’s light and easy to pack — that tea is one of the most essential items for any backpacker. He was glad to have remembered it. Sipping his tea, he took stock of his situation: On one hand he had three — no, four — energy bars left, but on the other hand, he was still completely lost. He finished his tea and felt calmer. Above him the same bird, or birdlike creature, was still circling, or maybe spiraling, down and back up again.

Then Parsifal had an idea — not a logical plan, certainly, but what good had logic done him anyway? None at all, was the answer. So — and even he had to admit this was a reach — if his eyes had failed to produce the desired effects, what would happen if he continued his search without them, if only for a while? Suppose, he wondered, he blindfolded himself and walked around for a bit? He thought of the blind men in his neighborhood. Without the distraction of sight would some deeper sense take over — smell, or hearing, or even taste? Well, possibly not hearing. Would he somehow be transported back to some earlier, wiser, childhood-self? There was only one way to know, and though it was slightly dangerous, true, it was also less dangerous than, say, crossing a busy street in the city without looking to the right and to the left, blindfolded or not. And after all, he could always take the blindfold off at any time.

He cut himself a stick so he could feel his way before him and wrapped a bandana around his eyes. Okay, Parsifal , he told himself, go forward, but be careful . You don’t want to fall into a pit like that second man you found when you were young, not so many days before — come to think of it — the disastrous forest fire where you left your mother, Pearl, behind forever, as she stood there coughing and bravely waving good-bye.

Читать дальше